SANTA MONICA, Calif. — Where Laurel Braitman is sitting is rather apt.

Braitman, whose first book, “Animal Madness,” won her fans and TED Talk acclaim, is unmistakable in a fringed, cream-colored jacket and thick, square glasses, perched on a tall chair near the back of Zibby’s Bookshop. It’s a small, airy paperback oasis along a bougie stretch of cafés and day spas. But it used to be a dry cleaners.

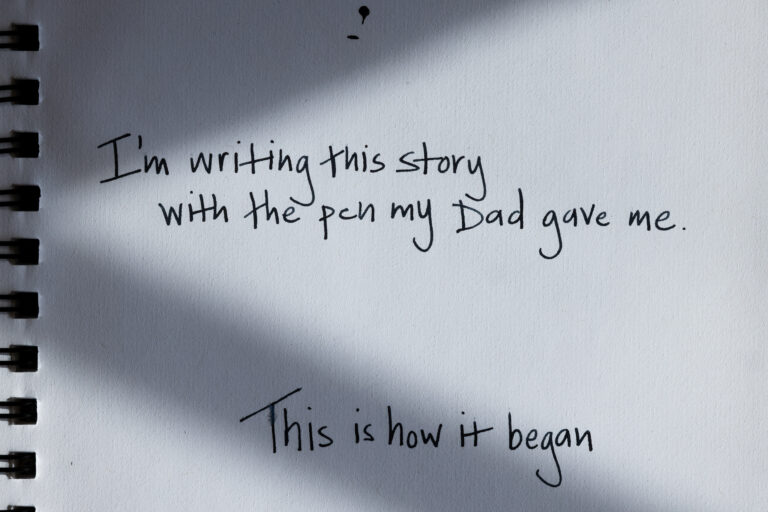

For the last few years, Braitman has been performing a kind of emotional dry cleaning for health care workers — accepting their dirty laundry without judgment, and then helping wash, press and fold it into something crisp and worthy of being worn out into the world.

She had already been teaching students as the director of writing and storytelling at Stanford Medical School’s program for medical humanities in the arts. Soon after Covid arrived, she felt compelled to start a virtual writing workshop, free for any health care professional with an internet connection to attend. “We will just go until you people don’t want to come anymore,” she said.

It’s still going. Every Saturday in 2020, 2021, 2022 — and every other Saturday in 2023 — she helps the people in the Zoom boxes tell their own stories. Gradually, the informal writing group has turned into a lifeline for many. Braitman, with her enthusiasm and earnest laugh, created a place where people could feel safe wrestling with the continuous gut-punches of working the frontlines of a pandemic. At its peak during lockdown, “Writing Medicine” attendance hit 150 people per session, Braitman said. At least 15,000 spots have been filled since the class started.

On this day, though, Braitman is at Zibby’s to talk about her own stories, captured in her new memoir, “What Looks Like Bravery.” The anecdotes are everywhere: She’s a few miles from the doctor’s office where her father, a cardiac surgeon, was told he had six months until cancer would kill him. Braitman tells the 15 or so attendees about that prognosis (she was 3 years old at the time), how it threw her family into over a decade of spontaneity, led by her dad who wanted to squeeze every last drop out of his life. His hunger to experience aliveness led to donkey taming, avocado growing, intense beekeeping, piloting, and twilight road trips to Vegas, among other things. And it made Braitman the inheritor of those many stories.

A few minutes into the talk, a palliative care physician, Alen Voskanian, ducks into the bookstore, bike helmet in hand. He is one of the many who found refuge in Braitman’s workshops.

His mother died in October 2020, and he needed a pressure release valve for his grief. “The Zoom environment gave me confidence,” he said.

When he shared his writing with the group, people were so supportive that he started to doubt whether they were giving him honest feedback. He asked Braitman’s opinion of his work, and then he learned the point: to let go. Creative writing isn’t science; even at its most specific, it’s subjective and infinitely interpretable. “It’s a way for me not to be perfectionist,” he said. Like so many people who end up physicians, Voskanian was a lifelong achiever. His tendency had been to cope with difficulty by over-performing — something he realized because of Braitman.

“Many of my students now, that’s their cry for help,” she said at the book event.

Braitman knows that life. Once her dad died, 14 years after his terrible prognosis, she devoted herself to doing impressive things: Undergrad at Cornell, Ph.D. from MIT, long stretches on riverboats in the Amazon basin, studying wolves, writing a New York Times bestseller, three TED Talks. She roamed and accomplished and avoided confronting her emotions — all to put in “the Laurel-is-good-enough file,” she said. “But that file could never be big enough.”

By the time she reached her late 30s, she was yearning for something more. For joy.

She had to traverse a chasm of pain to get there.

Her work at Stanford helped. In late 2016, she was teaching hundreds of clinical students and physician faculty members how to write and tell their stories in various formats. Her own anxieties were mirrored back to her, Braitman wrote in her memoir. The medical school was “a whole institution of people who believed in excellence as an analgesic, just like I did. Just like Dad had.”

By teaching a bunch of overachievers how to process their feelings and communicate with vulnerability, “maybe I’d figure out how to do it for myself too,” she wrote.

It was a symbiotic relationship: Braitman getting comfortable with the hard parts of her life’s story, while others, like Natasha Z. R. Steele, did too.

Processing the unimaginable

Steele grew up the daughter of healers so she became one, too. Her parents met in California’s Central Valley while doing migrant health work.

When she began her residency at Stanford in June of 2020, about a month after giving birth to her first child, the thing she most looked forward to was the day-to-day work of caring for patients — the work she’d watched her parents do with devotion. But it would take a grueling, winding path to get there.

Two weeks into residency, Steele was diagnosed with lymphoma and hospitalized, “incredibly ill,” she said. In just a few dizzying weeks, she had assumed three difficult roles — new doctor, new parent, and new cancer patient — all during a global pandemic.

“We had no vaccines. It was the worst summer of forest fires in a long time and the literal sky was orange. And I had this new baby and I had this terrible diagnosis,” she said. “It was so beyond belief that it was like telling someone about a movie you saw.”

Steele had to take time away from her residency to get treatment. It was especially hard to have to sit out during the start of a pandemic, when health care workers were running toward danger to save people’s lives. “The fact that I lost all my hair and I was getting infused with chemo rather than infusing other people was devastating for me,” she said.

She completed eight months of treatment and returned to work the day after her scans came back clean. But the building constantly reminded her of her illness. “Now I was expected to put on a different outfit and play a different role.”

Increasingly, she could feel the toll of acting — acting as if changing out of a hospital gown and into scrubs had redrawn the line between physician and patient, had planted her firmly on the side with control again. Steele could no longer pretend she was impervious to her patients’ suffering. She was both the doctor and the patient, and she felt it all.

“Every patient reminded me of some aspect of my own illness. Their primal fear was familiar, and the scent of their hospital gowns evoked memories of my own.”

Natasha Z. R. Steele, writing in the New England Journal of Medicine

Braitman showed up a year after Steele’s diagnosis to give a workshop to the residents. She opened with a prompt: Write down a step-by-step guide of how to survive something in the hospital. “I think I wrote something like, ‘How to survive being diagnosed with cancer when you are a doctor and you just became a mom,’” Steele said.

Writing quickly became a way for her to regain control of the narrative around her illness (a story that was ultimately published in the New England Journal of Medicine). By working with Braitman, she learned to unearth memories from that traumatic time and make meaning. Steele found her words could also heal — herself and others.

Re-humanizing medicine

Doctors, nurses, and other health care providers in the U.S. have unlimited demands for their attention. A writing practice that makes room for introspection might not seem like a valuable use of time, but proponents say it can help providers be more connected to their work.

“Medicine and science can be such challenging and rigid forms,” said Jenny Qi, a writer, poet and former cancer researcher. “Often we’re not encouraged, or if anything, we’re discouraged from thinking too hard about our feelings or overanalyzing our experiences because it can make the job harder to do.”

This re-humanization of medicine has been a concern for over a century, since medical education became more focused on biomedicine and scientific concepts than on the soft skills needed to be a good caregiver. The pivotal Flexner Report, published in 1910, moved the flesh-and-blood heart of medicine to the backburner as the field became more specialized, technical and rigorous. While those adjustments arguably made medicine better at curing and saving people, they came at a cost.

Almost immediately, people started pushing back, said Danielle Spencer, senior lecturer in the 23-year-old Narrative Medicine program at Columbia University (which takes a distinct, more formal and multidisciplinary approach). “You see these repeated clarion calls of people inside the profession and outside waving their arms and jumping up and down and saying, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, we’re losing something here along the way.’”

Today, humanities programs are common in medical schools, but it’s still hard to fit enough of it into jam-packed curricula. Often humanities are still considered less valuable than the meat-and-potatoes of basic and clinical sciences.

To Keisha Ray, director of the medical humanities program at UTHealth Houston’s McGovern Medical School, telling stories can be a powerful way to get people invested in health equity. Over her 15 years of teaching bioethics, she realized students weren’t really absorbing information on racial health disparities. The numbers would go in one ear and out the other. “I just thought there has to be another way to teach physicians and nurses about Black people’s health that encapsulates the entire lived experience of being Black in America,” she said.

So Ray developed the experiential race testimonies approach, or ERT, for collecting Black patients’ personal histories and using them to teach health humanities. The stories help medical and nursing students learn about the true impacts of disease, and of their own clinical decisions, beyond statistical data. Instead of learning that 50% of Black adults in the U.S. have hypertension, they hear a firsthand account of what it’s like living with high blood pressure.

“Stories are connective. They’re moving,” Ray said. “People may even forget the numbers…but they’ll remember the stories.”

The Covid pandemic only threw existing problems — burnout, dissatisfaction, time pressures, inequity — into starker relief. In her many conversations with health care professionals, Braitman realized that what’s grinding people down and driving them away is the feeling that their work isn’t meaningful. Medicine is “a calling,” she said. “And then they get there and they realize, ‘Oh crap, I didn’t do my calling today, but I worked for 17 hours.’”

Reflective writing isn’t “a Band-Aid for the American health care system,” she said. But it does give people a chance to remember why they got into this field in the first place, and how they might keep going.

The risks of vulnerability

Shireen Heidari was never afraid of the grueling conversations. In fact, she was drawn to palliative care because of them. Part of her work is helping patients with really difficult diagnoses manage their symptoms and figure out a treatment (or non-treatment) plan. But within that are a thousand small, heavy moments.

“They’re swirling through all of this uncertainty and fear and emotion — good, bad, the whole range. Oftentimes I’m entering into that story, whether I realize it or not,” she said. “I’m a person who happens to be witness to it.”

As Heidari transitioned into her specialty training, she found herself struck by the profound and hilarious and devastating things patients would say to her. She started writing down quotes in a little blue notebook.

As an English major who’d studied with the Royal Shakespeare Company, Heidari was naturally drawn to the written word. When she moved to Stanford almost seven years ago, she joined a writing group. That eventually led her to the medical humanities program, and to Braitman.

But it would take many months, and the start of the pandemic, to get her in Braitman’s writing workshops. “I’ve always had some degree of anxiety,” Heidari told STAT. “It was not something that I saw as detrimental. Covid just blew that open in a way that suddenly, I was really struggling.”

When taking a vacation didn’t soothe her angst, Heidari put pen to paper. As soon as she joined the Saturday morning Zoom calls, experiences started spilling out of her. Shortly thereafter, the journal Lancet Respiratory Medicine put out a call for stories about being a health care worker during Covid. Heidari submitted a piece, her first-ever submission to a medical journal, and it was accepted.

About a year after that, she wrote another that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine about her struggles with anxiety, and the stigma she felt in seeking help. Even writing about it felt sort of risky.

“Do I want to share publicly not only that I’ve struggled with anxiety…but also that when I did all the things that I was supposed to do and it wasn’t enough, I went to my doctor and I asked to be started on an antidepressant?” Heidari said.

Her concerns are justified. Many medical boards, before granting a license, ask clinicians about their mental health and whether they have ever sought treatment for mental health issues. “It irks me to no end. It makes me really angry, actually,” Heidari said. At best, it reinforces the idea that health care workers must be superhuman. At worst, critics say, it excludes talented, empathetic people from a field in which they’re desperately needed.

“I was not OK, and I needed to say that out loud. I needed to be able to talk about what I was seeing at work before I found it spilling out of my eyes as I watched a detergent commercial or stood in the shower.”

Shireen Heidari, writing in NEJM

Writing workshops alone won’t fix those kinds of systemic issues, but they can start a conversation about the problem, Heidari said. When the NEJM piece came out, she was flooded with hundreds of messages of thanks and support from health care workers. She now helps lead Writing Medicine classes.

“We have a lot of reckoning to do with our medical culture,” she said. “It’s changing and I’m grateful that it’s changing. And I think storytelling is one of the ways we do that.”

An ‘engine for empathy’

In a way, what Braitman and her students and many others are doing is as ancient as language itself. Storytelling itself is — has always been — the map, the connective tissue, the call for change.

As Braitman sees it, her work is straightforward: it’s helping people who work in medicine communicate more clearly and honestly. If a play or poem — or book, as in Voskanian’s case — emerges from her classes, that’s great. “But my aim really is to support their vulnerability in a field in which vulnerability is often punished,” she said. “Because I think it’s a great engine of empathy for themselves and for others.” The writing is the medicine.

Braitman knows that firsthand. Writing a memoir required her to take an expedition deep into the emotional jungle of her childhood, excavating memories that had been buried and pulling together a tale that felt true, even if it was difficult. She made sense of the bad and the strange and sweet — tubs of honey harvested decades ago by her dad in his beekeeping era, still sitting at her ranch today, ready to be spooned into a cup of tea.

As she signs copies of her memoir at the bookshop, Voskanian, now chief operating officer of Cedars Sinai Medical Network in LA, pulls on his bike helmet and says goodbye. Braitman tells a small circle of friends, “When the people in charge are writing poetry…”

That’s when metamorphosis can happen.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.