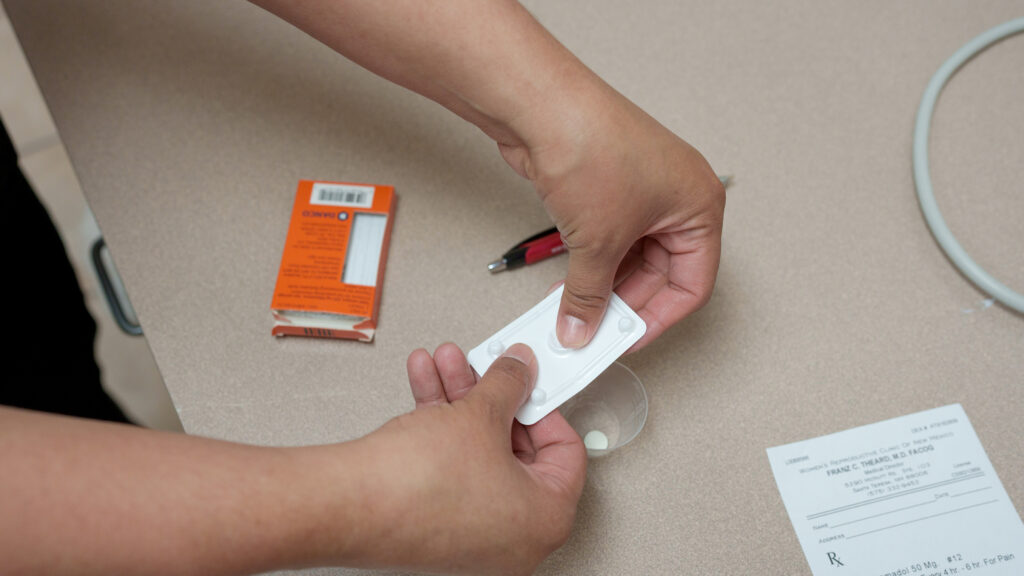

A dueling pair of federal court decisions has thrown the fate of the abortion pill mifepristone into jeopardy — and left regulators and drugmakers navigating uncharted territory.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the drug more than two decades ago. But that approval — and the agency’s broader authority — was cast into doubt with a decision on Friday by Texas judge Matthew Kacsmaryk which ruled that regulators had erred in letting the medicine onto the market. That long-awaited decision was swiftly followed by a Washington federal court ruling ordering the agency to ensure access to the pill going forward.

The two decisions throw the drug, also used to treat miscarriages, into legal limbo nationwide, regardless of state governments’ abortion protections. They also raise fundamental questions for regulators responsible for overseeing much of the country’s health care, and for the drugmakers that expend time and money to bring countless medicines to the market.

The pill’s future remains hazy as federal officials, pharmaceutical companies, and providers grapple with the tricky legal questions and the potential long-term ripple effects. STAT spoke with regulatory and legal experts about what could come next.

What happens immediately?

Mifepristone is still available, for now. Judge Kacsmaryk gave the FDA a week to appeal and put a stay on its withdrawal. The agency told STAT Friday that it has appealed the decision. The Justice Department followed suit with its own appeal on Monday, arguing that the plaintiffs did not have the standing to challenge mifepristone’s approval. The case will now move to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and could go to the U.S. Supreme Court if the appellate circuits are divided.

If the Fifth Circuit does not grant a stay, “it is likely that either Danco [Laboratories, the mifepristone maker] and/or the United States will ask the U.S. Supreme Court for a stay,” Danco legal counsel Jessica Ellsworth said in a media briefing on Monday, meaning the case could go straight to the panel of justices who last year overturned federal abortion rights.

The FDA declined to comment on its plan going forward beyond its Friday statement.

Several states including Washington, California, Connecticut and Massachusetts said they have started stockpiling mifepristone pills to ensure access if the Texas decision stands. While state officials would not technically be allowed to dispense the drugs, legal experts said the FDA could choose to ignore their actions by using what’s known as enforcement discretion.

What is enforcement discretion and how can the FDA use it?

Enforcement discretion means the agency has the right not to enforce certain rules, usually because they mark a major policy shift that needs to be implemented slowly. In the case of mifepristone, the FDA could essentially refuse to penalize providers who continue dispensing the drug.

The Washington court decision ordering the FDA to ensure mifepristone access “provides enormous political cover for the agency” to exercise that discretion if the Texas ruling stands, said Greer Donley, an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh Law School.

However, advocates for abortion access were reluctant Monday to focus on that option, arguing the best course to preserve access to the drug is to cement the FDA’s authority in court.

“It is premature to be talking about the FDA’s discretion. We really need to be focused on the case before it, and how wrongheaded this decision is,” said Nancy Northup, President and CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights.

How does the FDA balance its response to two conflicting rulings?

In issuing his ruling, Kacsmaryk said regulators “acquiesced on its legitimate safety concerns” due to political pressure at the time of the approval. The judge said that FDA approved mifepristone “mere months” after saying it needed more data, but also argued that pregnancy is a “natural process,” not an “illness,” so the drug wasn’t in FDA’s purview to approve. (Physicians and public health experts have countered that complications from miscarriages and other problems during pregnancy can be life-threatening.)

The Washington state lawsuit, meanwhile, was filed by Democratic attorneys general who argued that the FDA was too restrictive in its approach to mifepristone. They argued that FDA-ordered restrictions like limiting mifepristone to certified providers and a sign-off from patients that they intend to end a pregnancy are unnecessary — and in issuing his ruling, that judge said the FDA must not take any steps that would restrict access in the states involved in the lawsuit.

The outlook is so fluid that circumstances are certain to change in coming days as courts consider the appeals and the differing scenarios that could play out. Already, there is talk that one or more parties involved may turn to the U.S. Supreme Court, according to sources.

Meanwhile, the FDA is caught in the middle as the Biden administration and others involved in the litigation are planning for different scenarios, like a round of war games. If the Biden administration fails to win a stay — or delay — of the Texas court ruling, then the mifepristone approval is null and void. Yet the judge in Washington State issued a preliminary injunction that the FDA should not compromise availability of the pill.

“For the FDA, the ideal outcome is not to have this order (from the judge in Texas) go into effect, because it would be disruptive if it does,” explained Susan Lee, a partner at the Goodwin law firm who specializes in FDA regulatory issues. “And if the other order (from the judge in Washington State) does go into effect, it puts the FDA in the position of not being able to comply with either order.

“But in some ways, the FDA would get what it wants, because it would prefer the status quo.”

Could the makers of mifepristone apply for a new FDA approval?

If the mifepristone approval is permanently revoked, the drug’s manufacturers will likely have the option to refile papers with the FDA for marketing approval again. How so? The FDA now has a risk management program in place — called a REMS — that is designed to ensure safe and effective use of the medicine. That program was not in place when mifepristone was approved in 2000.

The FDA could approve a so-called new drug application through usual procedures, according to Lee. The FDA could, if it proceeded with an application, require a REMS as part of its review as it proceeds toward approval.

There is also a possibility of approving the pill for miscarriage management. Doctors are legally allowed to prescribe the medicine for that purpose — and frequently do — but the pill has never been formally approved to treat pregnancy loss. This would be another way to return the pill to the market.

What could this mean for other FDA-approved drugs? And what do drugmakers want to see the FDA do?

The pharmaceutical industry is up in arms over the Texas ruling. Hundreds of executives from big pharmaceutical companies and small biotechs signed an open letter that was released on Monday calling for the court order to be reversed and urging support for the “continued authority of the FDA to regulate new medicines.”

The key argument the executives make is that innovation is at risk.

“The overarching question is should a judicial process, biased or not, be allowed to overrule the approval process done by experts?” said Kenneth Moch, who heads Euclidean Life Science Advisors, which works with early-stage companies. “If there’s more risk, then the cost of developing and testing new medicines will be higher. As you increase risk, you decrease investment.

“It’s pure economics. It’s not really up for debate, whatever the number of drugs you may argue will be affected, it will be something. Why would an investor and a company take the risk of developing a drug where there’s a legal or social pressure against it coming to the market? There’s concern that decisions are being made to overrule the experts that may not be related to science at all.”

He experienced this firsthand. Nearly a decade ago, he ran a company called Chimerix that became embroiled in an episode that jumpstarted a law known as Right to Try. The legislation was created to bypass the FDA and hasten access to experimental treatments. The effort largely failed, but became a symbol of efforts by outsider groups to override FDA decision-making authority.

For such reasons, the FDA should continue as it always has and approval decisions should be quite separate from the question of who might sue it, said I. Glenn Cohen, who heads the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, & Bioethics at Harvard University.

“This is one of the things that I think is best about the agency— the insulation of its decisions and the tendency for those decisions to rely so heavily on experts,” he said in an email. The Right to Try law and other efforts may change how the agency handles approvals, but the “approval process should stay as untouched by threats of litigation as possible.”