One note to start: In today’s special edition of DD, we seek to help you understand why Silicon Valley Bank unravelled so suddenly, what it means, what comes next and how it could reverberate across financial and private markets.

Welcome to Due Diligence, your briefing on dealmaking, private equity and corporate finance. This article is an on-site version of the newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent to your inbox every Tuesday to Friday. Get in touch with us anytime: Due.Diligence@ft.com

DD breaks down the fall of SVB

On Friday, Silicon Valley Bank was shut down by US regulators.

The collapse of the $209bn-in-assets lender marks the second-largest bank failure in US history after the 2008 shuttering of Washington Mutual. It comes after SVB tried and failed to raise $2.25bn in new funding to cover losses on its bond portfolio and had begun looking for a buyer to save it, according to people with knowledge of the efforts.

The bank’s failure has sent shockwaves through Silicon Valley, where it’s a big lender to many of the largest venture capital firms and their portfolio companies.

Let’s back up for a second . . . what’s SVB?

Founded as a small California lender 40 years ago, SVB built a powerful niche during the tech boom, outmanoeuvring Wall Street giants such as JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs, in funding tech companies’ growing affinity for debt as they sought to stay private for longer and avoid diluting equity positions. It also was a critical lender to venture capital and private equity firms that increasingly utilised leverage at the fund level.

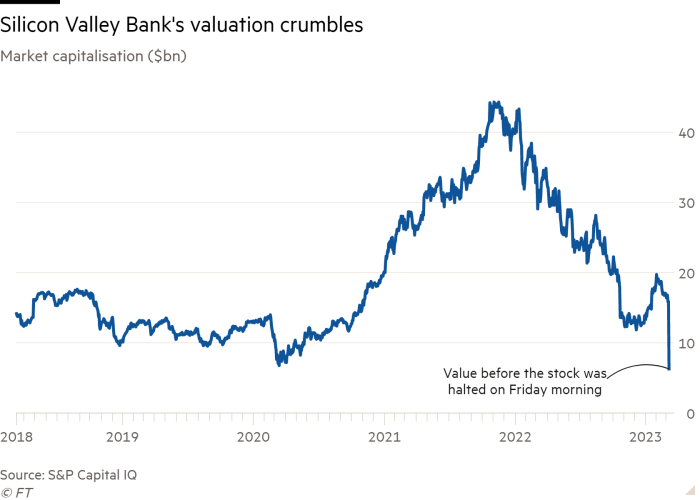

But its codependent relationship with start-ups backfired as the tech world was rocked by rising interest rates that increased SVB’s funding costs while simultaneously causing the biggest collapse in tech valuations since the dotcom era. SVB also found itself exposed: its market capitalisation tumbled from a peak of more than $44bn less than two years ago to just $6.3bn by the close of trading on Thursday.

How did we get here?

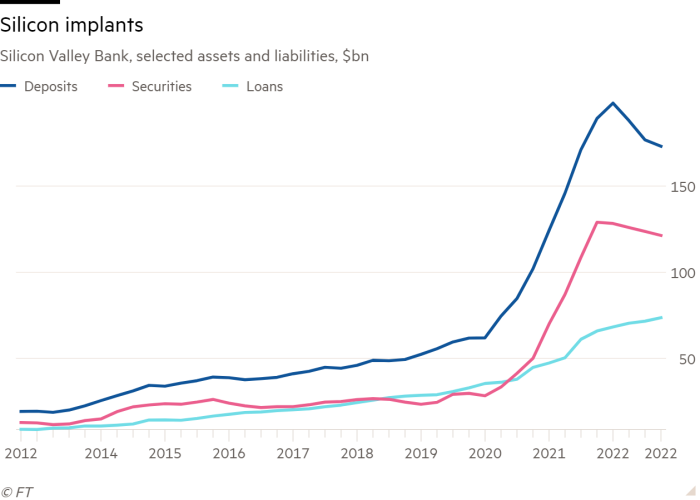

The lender’s troubles stem from a misfired bet on interest rates made at the height of the tech boom, as the Financial Times reported in detail last month. Our colleague Rob Armstrong explains the crux of the issue in Unhedged: SVB’s tech start-up clients, flush with funding from venture capitalists during the speculative coronavirus tech boom, were inundating the bank with cash (the dark blue line).

Unable to give loans (light blue line) at the same speed, SVB decided to put a staggering $91bn in deposits somewhere else: long-dated securities such as mortgage bonds and US Treasuries (red line).

Here’s why that’s bad, Unhedged explains: “It gave SVB a double sensitivity to higher interest rates. On the asset side of the balance sheet, higher rates decrease the value of those long-term debt securities. On the liability side, higher rates mean less money shoved at tech, and as such, a lower supply of cheap deposit funding.”

When the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates, this asset/liability mismatch meant that the bank faced a margin squeeze.

In addition, SVB’s bond portfolio plummeted by $15bn in value . . . nearly as much as the bank’s tier 1 common equity.

Making things worse, the subsequent share sale, meant to shore up the bank’s balance sheet, blew up.

SVB hoped to sell $1.25bn of its common stock to investors and an additional $500mn of mandatory convertible preferred shares. It had received a commitment for a $500mn investment from its longtime client General Atlantic that was contingent on the share sale being completed.

But as its bankers at Goldman built the book on the share sale, SVB’s stock was in the middle of its biggest-ever decline on Thursday, erasing $9.6bn off its market capitalisation. Goldman was able to drum up enough demand for the $1.75bn share sale, according to people briefed on the matter, but the rapid deterioration in SVB’s business made the deal untenable.

SVB’s tech clients had already been pulling — or burning — cash as venture capital funding dried up. When its fragility was exposed, customers, including companies advised by venture capitalists such as Peter Thiel, pulled their cash, as Bloomberg has reported.

SVB’s customers were an impatient bunch and created a big hole quickly. They held large deposits that were beyond the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s guarantees, and were prone to leave at a sign of trouble — $151bn of the bank’s $173bn of its deposits were uninsured. SVB could do little to stop the bleeding.

That day, as bankers worked their phones, SVB clients attempted to withdraw $42bn. The sum was so large that Goldman bankers knew they couldn’t go ahead with the offering without first re-briefing investors.

By Friday morning, SVB and Goldman had abandoned the effort as they began to search for an emergency buyer.

Bondholders are also bracing for steep losses: SVB’s senior debt was trading at about 45 cents on the dollar on Friday, and its junior debt fell as low as 12.5 cents.

What happens next?

The collapse has left Silicon Valley start-ups scrambling to pay staff and identify sources of back-up funding after US regulators at the FDIC intervened.

The FDIC only guarantees bank deposits of up to $250,000, a sum well under most of its early-stage tech and venture capital clients’ account balances.

Many SVB depositors that spoke to the FT are hoping the bank will be bought out of receivership and that its new owner will reopen accounts and resume lending.

The collapse could also have big ramifications for investment firms on the other side of the pond. Many European private equity and credit firms turned to SVB for fund-level leverage facilities that help juice their returns, people in the know tell DD.

The FT also revealed that the Bank of England plans to put SVB’s UK arm into resolution after it applied for £1.8bn of emergency liquidity on Friday.

Where we don’t want to get too ahead of ourselves is when it comes to the potential fallout for the rest of the banking industry. SVB was an outlier in both its exposure to the tech industry and its unpreparedness for the Fed’s steep increases in interest rates over the past 12 months.

Another big difference between SVB and its peers is that the majority of its customers are businesses, not retail investors — meaning that they’re more likely to pull their cash if yields fail to impress, or simply incinerate their accounts with cash burn.

The mood in Silicon Valley for many is panic. “This is an *extinction level event* for start-ups,” Garry Tan, president of start-up accelerator Y Combinator, wrote on Twitter on Friday.

And one smart read to finish: The FT’s Tom Braithwaite offered a glimpse into the chaos of an FDIC takeover back in 2011. Spoiler alert: it was messy.