On a spring day in the late 1980s, pediatrician Mark Schleiss was confronted with a difficult case: a months-old infant who had developed pneumonia. While many infants with pneumonia recover, this particular baby had grown so sick he was admitted to the ICU, where he died. The autopsy showed he had disseminated cytomegalovirus, which had caused his pneumonia and then his death.

“There’s nothing that makes an impression on you as a young physician quite like going to the autopsy of one of your own patients,” said Mark Schleiss, who cared for the child. He already knew he would train in infectious diseases, including HIV. But the diagnosis of CMV drew his interest.

“I was struck by… how little anybody knew about CMV,” said Schleiss, now also a physician-scientist at the University of Minnesota.

Even if doctors had caught the condition, there was little they could have done: Antivirals were relatively new then, and the first drug for CMV would not be approved for another year. In the decades since, there has been little progress in treating CMV, which appears in 20,000 babies born each year in the U.S., and leaves an estimated 4,000 infants annually with devastating long-term health problems. There is no vaccine to protect against the virus, and the best-studied and most-used treatments are the antiviral approved three decades ago and another structurally similar drug.

And experts say there is little public awareness about CMV compared to other viral infections that can infect a fetus in utero, such as HIV, Zika, and toxoplasmosis, all of which are far rarer than CMV infections. Professional societies recommend pre-pregnancy counseling and monitoring for HIV, but not for CMV. And testing for the infection in newborns isn’t widespread.

“Through my entire career, it’s been so clear that this field is really lacking in progress,” said Laura Gibson, an infectious diseases physician at UMass Memorial Health. “It’s just been frustrating to all of us in the field over decades.”

That is starting to change, as state public health committees and legislatures begin to debate whether to mandate doing more robust screening for CMV. In 2019, Ontario became the first region in the world to test every baby for CMV. This year, Minnesota followed suit.

CMV is short for cytomegalovirus, a catch-all phrase that describes both a group of viruses (one of which infects humans) and the disease it causes. Like the flu, it’s incredibly common and often harmless, shrugged off as a non-problem in a dizzying world of pathogens. But like HIV, CMV is resilient and tough to clear out: CMV cycles between periods of dormancy and activity. Once someone is infected, they carry the virus throughout their lifetime.

“It’s a constant interaction between the virus and the immune system, as opposed to the flu that comes and goes,” said Gibson. “It lives with us for life.”

A CMV infection is particularly devastating for a fetus, because the virus has a proclivity for infecting neural stem cells. One study found CMV increased the risk of stillbirth by more than 8 times. In babies who survive, the virus can cause neurodevelopmental delays and disabilities, including cerebral palsy, seizures, vision impairment, and progressive hearing loss.

Hearing loss is by far the best studied consequence of congenital CMV — CMV is the foremost non-genetic cause. But it’s not always apparent: 15% of infected babies will appear healthy at birth, only to lose their hearing later in life. “Congenital CMV is often a progressive disease,” Gibson said. “Whatever we find on testing at birth, any of those parameters can get worse over time, over years.”

Yet CMV receives relatively little attention compared to other prenatal infections that also have significant health impacts, but are much rarer, such as Zika. Even doctors who specialize in caring for children said they were taught little about CMV in their training.

Albert Park, the chief of pediatric otolaryngology at the University of Utah, graduated medical school in 1990. “I don’t recall CMV ever being mentioned,” he said. “At that time, it certainly was not emphasized.”

Megan Pesch, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at the University of Michigan who completed her medical degree two decades later, said that the only time CMV was mentioned in her training was as the letter C in the acronym TORCH, used to help students remember a set of congenital infections.

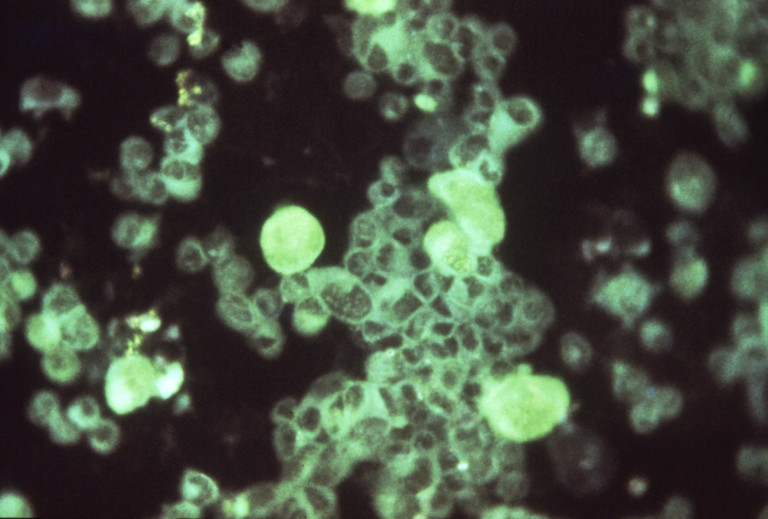

“It’s so common, but it really was not emphasized in my medical training at any point other than just to answer that question on my boards,” she said of CMV. In her residency program’s review course, which gave students “binders upon binders of notes,” there were only 2 brief slides on congenital CMV: the first was an image of a newborn with visible viral infection; the second had a few bullet points contrasting symptomatic and asymptomatic babies.

Pesch now has an intimate understanding of CMV’s toll — but not from her medical training. In 2018, after she had completed her residency and fellowship training in pediatrics, she gave birth to her third child, a daughter named Odessa. “She came out screaming and crying and great,” said Pesch, who is also president of the National CMV Foundation. “Seven and a half pounds. Perfect size.” There was a fold-out couch in the recovery room, and when Pesch closed it, there was a sudden, loud sound. Her newborn daughter, Odessa, heard the noise too and startled, as was expected.

About a day later, though, the first sign that something might be wrong emerged. Odessa did not react to the sounds in her first newborn hearing screen. “A lot of babies fail their newborn hearing screen. Nine out of 10 times it’s just a false positive,” said Pesch. “So I was like, ‘I’ll just not worry about it.’ I’ve spent my career telling moms not to worry about it.”

A month and a half later, Odessa didn’t pass a repeat screen. Further testing revealed she was completely deaf. An otolaryngologist at first suspected the cause was genetic.

Pesch was the one who asked to test Odessa’s urine for CMV and gathered the necessary supplies, when she was 3 months old. It came back positive, which could have signaled either congenital CMV or an infection after she was born. A head ultrasound revealed abnormalities consistent with congenital CMV. By this point, Odessa was 4 months old, and she started an off-label course of twice-daily antivirals for the next six months. (Experts recommend treatment start within a month of birth when possible.) A blood sample taken from when she was days old later tested positive for congenital CMV.

Odessa, now 4, needs braces to support her legs. She tried cochlear implants, but they didn’t work well. She also has autism, which her mom says is common in congenital CMV patients.

“I feel I never have come back from maternity leave because I spend my days driving her to therapies,” said Pesch. “CMV has just made a lot of things harder for her and it feels unfair.”

“It’s not like we’ve lost hope, because she’s an amazing kid, but things are just so different for our family, which is beautiful and also really hard.”

Physicians can only intervene in the days and weeks after birth, not before. There are no tests that conclusively determine active CMV infection of a fetus during pregnancy. And in the small subset of cases where a parent’s test shows a new CMV infection, there are no proven medicines to treat a fetus in utero.

Professional societies don’t recommend CMV screening for these reasons. As a result, said Pesch, parents rarely learn about it. “ACOG actually recommends that people do not counsel their patients about CMV prevention because to implement it would be burdensome and impractical for women,” she said, referring to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “I’m baffled why people don’t take it more seriously.”

Where the scientific and medical communities have arguably made some progress is in newborn screening tests. Nearly every baby born in the U.S. gets a heel prick in the hospital to test for rare, often hidden health conditions that are fatal or life-altering unless promptly treated, and all babies also undergo hearing tests. Historically, these tests haven’t looked for CMV at birth.

In 2013, Utah became the first state to start some sort of screening for congenital CMV. The legislature passed a bill that requires public education of CMV and, when a newborn has failed their hearing test, the option to test for CMV. The lead sponsor for that bill was a state representative whose 2-year-old granddaughter had become deaf from congenital CMV.

Unlike conventional newborn screening, performed by state health departments, Utah providers test urine, which contains more DNA from the CMV virus. Hospitals test the samples and report the results to the health department, which tracks follow-up care.

Today, 14 states perform follow-up testing for CMV when a baby doesn’t pass a hearing test. But the approach is limited in its ability to catch CMV, due to its progressive nature. An influential study found that around half of congenital CMV patients who later develop hearing loss are missed because they pass hearing screening early on.

Testing every baby for CMV, what the field calls universal screening, is another matter entirely. “We just haven’t been able to implement that at Utah,” said Park.

Universal CMV screening has “been debated in many states for years,” said Schleiss. Even a decade ago, Utah’s law was controversial.

States can mandate specific newborn screening tests be performed without the explicit consent of parents — which means state health departments are very particular about deciding which conditions to screen for.

“The idea is the state is taking rights away from parents. They’re saying, ‘This condition is important enough for us to screen that you don’t get a say in whether or not your baby is screened for this mandated condition,’” said Anne Comeau, deputy director of the New England Newborn Screening Program and a professor at UMass Chan Medical School.

“Typically, you need a screening test for a disease that has a bad outcome, if it isn’t detected, for which an intervention is available,” said Schleiss. Among experts, CMV is controversial from that perspective. It causes clear issues — chief among them, progressive hearing loss — in 15% of cases. But in the other 85%, any potential health effects are less apparent. (A continuing concern is that the non-hearing effects of congenital CMV are understudied because most CMV cases aren’t identified; in a small study of 34 clinically asymptomatic infants with congenital CMV, 56% had some form of abnormality identified upon further study.)

Schleiss has continued to push for greater awareness of CMV over the decades. Along with affected families, he started lobbying Minnesota legislators in 2015 on the issue. One proposal for CMV education made it into a spending bill and to the governor’s desk, where it got vetoed in 2018.

In parallel to that work, Schleiss started working with the Minnesota Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to test blood and urine samples of newborns for CMV. The results of that study, published in February 2021, showed that blood from heel pricks could achieve a sensitivity of around 75%, due in large part to advances in DNA extraction technologies. This was akin to a proof of concept that made blood tests, easily integrable into existing newborn screening panels, feasible. “Do we need a better test? Yeah, we do,” said Schleiss. But, he added, “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

In 2021, Schleiss campaigned for another bill that would require an outreach program for congenital CMV education among prospective parents and health care providers. That bill was named the Vivian Act — for a now-9-year-old Minnesotan with congenital CMV — and would also require Minnesota’s newborn screening advisory committee to consider adding CMV to the state’s screening panel. Schleiss nervously followed the voting online, “on pins and needles,” he said.

The bill passed, and the question came before the screening committee. The panel of experts examined how accurate the tests were, whether insurance companies would balk at the cost of testing, and whether health systems and labs would need more trained staff.

Last year, they agreed it was worthwhile. The health commissioner signed off on their recommendation, and last month, Minnesota became the first state to screen all newborns for congenital CMV.

“It’s an opportunity to help more families, to help more kids,” said Jill Simonetti, the manager of the newborn screening program in Minnesota. This summer, meanwhile, New York plans to start a single-year pilot study of universal CMV screening.

Some physicians still aren’t convinced that universal screening is the right move. Carlos Oliveira, a pediatric infectious diseases physician at Yale and director of its congenital infectious diseases program, has evaluated many kids for CMV since a Connecticut law mandating targeted CMV screening came into effect in 2016. His patients receive urine draws, blood samples, eye exams, ultrasound imaging, and sometimes MRI scans. He said parents often feel a sense of guilt with the diagnosis, because the virus is passed from mother to child, and anxiety over the potential health impacts.

But more often than not, he said, the stress parents are put through doesn’t turn out to be warranted. “The problem with CMV is that the majority of babies who are infected before birth don’t have any problems,” Oliveira said. “I don’t really care if the baby has CMV if nine out of 10 of them are going to have absolutely no long-term ramifications.”

“That’s my problem with universal screening,” he summed up. “It’s a huge policy that affects a lot of people and I have a hard time justifying the good for that.”

It’s an increasingly common issue in screening for disease, as advances in science allow for detecting more disorders: how to best balance the needs of some patients against the risks of false alarms or unnecessary treatment. The field will need to grapple with that and other questions, such as how accurate a screening test needs to be to prove worthwhile, as it looks to finally move forward on CMV. Massachusetts is now considering a CMV screening bill. During a public hearing in 2021, a deafblind educator concluded her testimony with an exhortation from Maya Angelou: “When you know better, do better.”

Experts may not yet agree on how best to tackle CMV, but to some in the field, the debate around screening alone is a sign that the medicine is doing better.