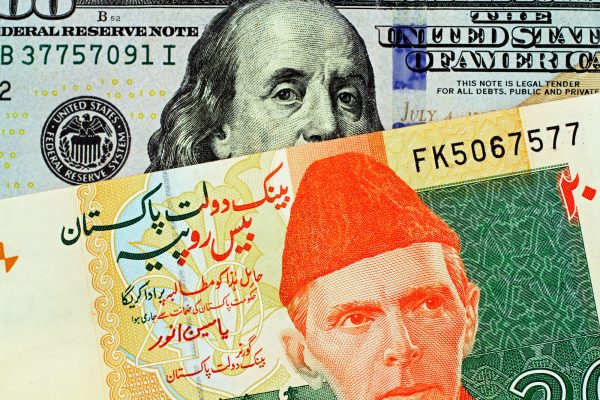

Pakistan is ensnared in a classic sovereign debt trap: too much foreign currency denominated external debt, too few foreign exchange resources, and too little cash flow denominated in foreign currencies to service contractual periodic interest and principal payments on such debt. The current approach to alleviating the excruciating pain of the debt trap is to seek relief via two routes: (1) taking on more new external debt to finance current required debt service payments, and (2) restructuring existing external debt to lower the debt service burden via a combination of capitalization of accrued interest payments, resetting required principal payments, and extending debt maturities.

Quite bluntly, the current path is a detour to a dead end – what lies at the end of the rainbow is a more bearable form of the debt straitjacket, not an exit from the debt trap. It is time to think outside the box keeping in mind Shakespeare’s prudent advice in “Hamlet”: “Neither a lender nor a borrower be.” The key to escape Pakistan’s sovereign debt trap is hiding in plain sight – deleveraging.

Simply put, deleveraging is financing without debt via two channels: grants and equity. Multilateral creditors such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and Asian Development Bank would convert existing loans to Pakistan into grants, while private holders (e.g., portfolio investment funds, sovereign wealth funds, and corporate investors) of existing Pakistani sovereign debt denominated in foreign currencies would swap such debt for shares of state-owned enterprises that are to be privatized. Any new financing would be in the form of grants and/or equity.

Deleveraging shifts the focus from Pakistan’s capacity to pay to Pakistan’s potential for growth and is designed to ensure financial resiliency. Deleveraging reflects an assessment that there is likely to be economic and financial stress, and perhaps distress, over the short and medium term (up to 10 years), but there will be economic and financial recovery and growth over the long term (10-20 years). What Pakistan needs is patient capital – in the form of grants and equity – that is willing to share downside risks in return for the potential upside rewards of economic growth and development.

Deleveraging: A Vote of Confidence

Pakistan is clearly on the brink of default and financial bankruptcy, reflecting a “perfect storm” of stagflation, a worsening of the already heavy external debt burden due to rapidly increasing interest rates designed to combat inflation, the devastating impact of the August 2022 floods, and political tension (both internal, with national elections likely before year-end, and external, with the continuing Russia-Ukraine war). All three major international credit rating agencies are unanimous in their assessment of a very high likelihood of default and currently rate Pakistan sovereign debt accordingly: Standard & Poor, CCC+; Moody, Caa3; and Fitch, CCC-.

Not surprisingly, trading in Pakistan sovereign debt reflects its “junk bond” status. For example, Pakistan’s benchmark sovereign bond, 7.375 Percent Notes due April 2031 ($1.4 billion outstanding), currently trades at about a 66 percent discount. So, $1 face value of Pakistan sovereign external debt is valued at only 34 cents in the international financial markets.

Its current dire situation notwithstanding, Pakistan, a geostrategically important nuclear-armed state, is not a failed state in terminal decline, nor is it doomed to endure a lost decade. The World Bank, in its latest economic growth projections, estimates Pakistan’s GDP growth rate will be an anemic 0.4 percent for fiscal year (FY) 2023, but will gradually recover to 2 percent in FY2024 and 3 percent in FY2025. With steady recovery as a base, the potential for strong economic growth can be unlocked in the medium term. Given a consensus on political accommodation and the administrative and political will to implement broadly agreed economic reforms, the fruits of economic growth and development can be harvested over the long term.

In December 2022, Coca-Cola Icecek (the Coca-Cola bottler for Turkey, Central Asia, and the Middle East) decided to increase its investment in Coca-Cola Pakistan from a 50 percent ownership interest to a 100 percent ownership interest via a cash purchase for $300 million of the remaining interest in Coca-Cola Pakistan held by its partner, The Coca-Cola Company. The move is an early sign that sophisticated equity investors accustomed to operating in challenging emerging markets believe in Pakistan’s long-term growth prospects.

Privatization and the Debt Trap Solution

A consistent refrain of the IMF, World Bank, and Asian Development Bank – the three largest multilateral lenders to Pakistan – has been the recommendation to privatize state-owned enterprises (SOE). Privatization would have two objectives: raising cash via the sale of state-owned assets and reducing the budgetary burden of supporting poorly performing loss-making state-owned enterprises.

With that in the mind, swapping Pakistan’s existing external sovereign debt held by private creditors for equity in state-owned enterprises can achieve three objectives: reduce Pakistan’s external sovereign debt (i.e., further the goal of deleveraging), increase foreign corporate and institutional portfolio investment in Pakistan enterprises that are to be privatized, and reduce the budgetary burden of supporting SOEs. It is worth considering how such a sovereign debt-to-equity swap program might be structured in the context of deleveraging and privatization.

Per the IMF, Pakistan’s total foreign currency debt of about $99.1 billion amounted to about 28 percent of GDP in 2021. Pakistan’s total foreign currency external debt held by foreign commercial creditors is estimated to be about $19.7 billion (20 percent) with the balance of $79.4 billion (80 percent) held by multilateral and bilateral creditors. A Pakistan sovereign debt-to-equity swap program in the context of deleveraging and privatization would be targeted at foreign commercial creditors with the objective of persuading them to swap their holdings of foreign currency denominated Pakistan sovereign debt for common stock of state-owned enterprises that are expected to be privatized (i.e., the government of Pakistan’s equity ownership interest would be reduced completely or to an insignificant minority equity stake). To that end, Pakistan’s government would prepare a list of state-owned enterprises to be privatized, of which some may already be publicly listed.

A debt-to-equity swap program could be structured to have two prongs: (1) individual SOE transaction to transfer control (i.e., at least 51 percent equity stake) to a foreign company, and (2) transactions involving SOEs already listed or expected to be listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (with the government of Pakistan selling a portion of its holdings with the declared objective of reducing its ownership stake to less than 50 percent). A specific issue of Pakistan sovereign debt would be identified as an appropriate instrument for purposes of the debt-to-equity swap with respect to a particular transaction. For purposes of illustration, the 7.375 Percent Notes due April 2031 ($1.4 billion outstanding; listed on Frankfurt Bourse) will be used as the debt instrument.

An example of an individual transaction to transfer control of an SOE to a foreign company could be the sale of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) to a foreign airline company. For argument’s sake, assume based on a mutually agreed valuation, a 100 percent stake in PIA would amount to $300 million. Foreign Airline X would acquire an appropriate amount of 7.375 Percent Notes at the current market price and offer such notes to the government of Pakistan at a mutually agreed valuation (somewhere between the current market value and the face value of the note) as payment for the 100 percent equity stake in PIA.

The same pattern would be applicable in the case of a foreign portfolio investor wishing to purchase from Pakistan’s government a $300 million portion of the shares in State Life Insurance Corporation of Pakistan, in anticipation of a possible IPO and listing on the Pakistan Stock Exchange.

Just to be clear, the foregoing examples are purely illustrative. But deleveraging via debt-to-equity swaps is not a new concept – Chile used such an approach with considerable success in the 1980s.

While deleveraging via debt-to-equity swaps is driven by financial and economic considerations, deleveraging via the conversion of debt into grants is driven by other considerations, such as philanthropic impulses or geostrategic priorities. Multilateral financial institutions such as the IMF, the World Bank, and the ADB have often forgiven debt in the name of poverty alleviation. Apparently, Pakistan is not considered to be poor enough to arouse the philanthropic impulse of multilateral institutions.

Instead, Pakistan by virtue of its geographic location (it shares borders with India, China, Iran, Afghanistan, and overlooks the confluence of the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf) might try to monetize its geostrategic value. Islamabad can seek to persuade the controlling shareholders of the multilateral institutions that, in the context of the tectonic shift from unipolarity to multipolarity, it is in their geostrategic interest to convert the debt owed by Pakistan to such institutions into grants. The IMF, World Bank, and ADB are controlled by a group of 10 countries who collectively have a majority of the voting shares – the United States, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, Australia, and Spain. While there is no guarantee a realpolitik approach will be successful, surely it is worth making such an effort.

Pakistan has the key to escape its sovereign debt trap and should use it.