The current backlash against queer and trans people, led by a vivified cultural right, may have come as a surprise to younger people who assumed their rights and protections wouldn’t backslide. For this potential audience most of all, “Last Call,” a rigorous yet emotionally vivid documentary series on HBO, will come as a startling depiction of all-too-recent history, and a call to stand united in the face of a world’s worth of threats.

Produced by, among others, recent Oscar nominee Howard Gertler (“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed”) and directed by Anthony Caronna, “Last Call” tells a set of stories that tend to begin at a piano bar. In the early 1990s, a cohort of gay men, often in culturally forced heterosexual marriages and living their true lives only after dark, frequented various drinking establishments in New York City; time and again, one of this set would turn up not merely dead but dismembered, in a sort of brutal testament to antigay feeling.

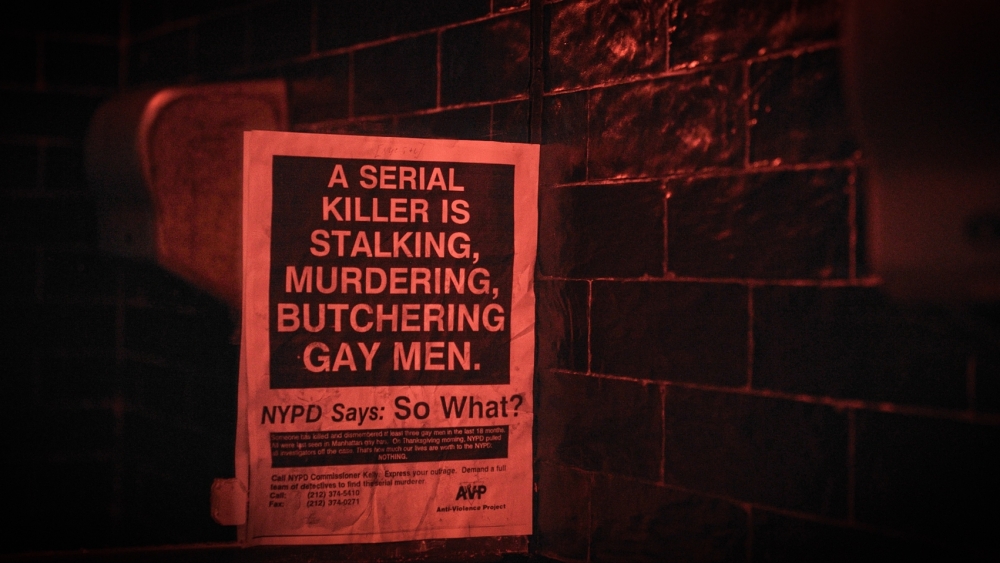

This grim warning seemed to resonate more with queer people, who were already facing down the AIDS crisis and who grew increasingly fearful, than with law enforcement. Though based on Elon Green’s 2021 book, “Last Call” uses the tools of documentary to assemble a collage of homophobia, and of queer resistance to it. Caronna’s series makes the case that, in a climate still defined by the homophobic activism of Anita Bryant and Pat Buchanan, the police were, at best, less than utterly committed to cracking the case. We see this climate both broadly and, as it pertains to the New York Police Department, deeply; an archival “Oprah” clip sees a guest correct her reference to “gay bashing” with an offensive slur and chalk the crime up to “goofiness,” while Ray Kelly, the former NYPD commissioner, is shown defending his membership in the Emerald Society, a fraternal organization with an antigay platform.

All of this creates a thrumming, threatening backbeat to the story, and we’re certainly shown every contour of the crimes, too. (I’ll admit it had not been previously known to me that “overkill” was not just a metaphorical term, but one used in medical contexts to describe injuries vastly beyond what would cause death.) But the soulfulness of “Last Call” exists beyond or outside police-blotter details. The victims — and I use the word advisedly, as they didn’t just fall prey to a crime but were born into a society unready to accept them — come alive in the testimonials of those who loved them.

This aspect, the degree to which “Last Call” is ready to remember its subjects as real people who yearned for affection and who loved their siblings and who were curious about what joy they could wring out of an unfeeling world, is what makes it transcend. Its settings, like the still-extant Townhouse bar, feel lit with potential harm but also with the baleful sort of affection that comes when people in danger look out for one another as best they can. “Last Call” exists as a critique of systems that moved too slowly to solve a case of serial murder. It also has within it a big-hearted examination of a sort of queer life that’s less in evidence today, in a more open era. In a moment of renewed threats and, more than one might like to admit, deep animus from some major subset of society, this is vital and urgent history.

“Last Call” premieres on HBO and streams on Max Sunday, July 9 at 9 p.m. ET, with new episodes to follow weekly.