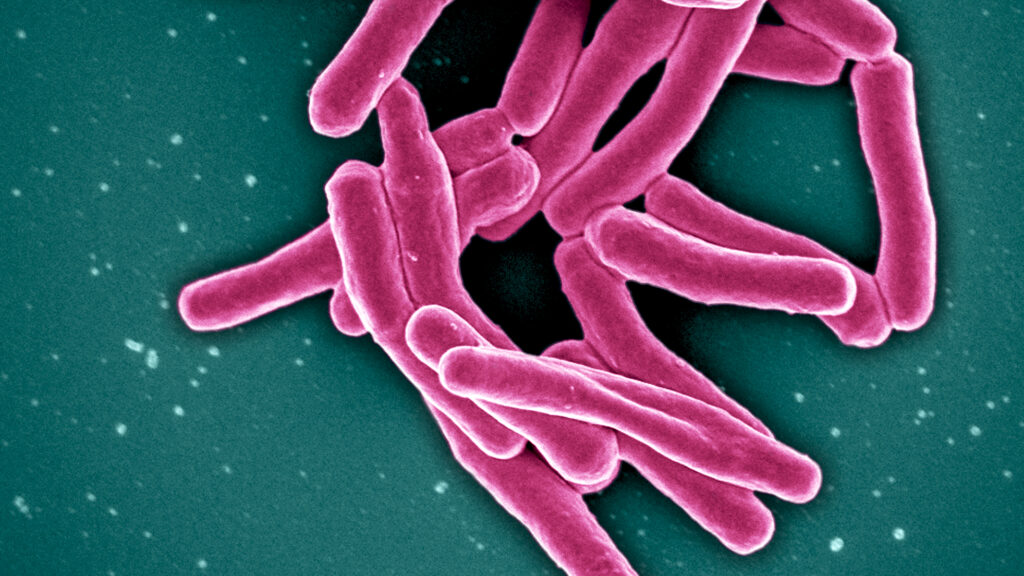

One person has died and at least four have been sickened by tuberculosis in infected bone materials, an outbreak that has cast a spotlight on the shortcomings of testing for such tissue products.

It’s the second tuberculosis outbreak linked to the biomaterial device company, Aziyo Biologics. In 2021, Aziyo’s product killed eight people after orthopedic and dental surgeons unwittingly implanted infected bone grafts into patients. The latest outbreak led Aziyo to recall all materials made from the same donor in July. One person has died from TB, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has since identified 36 exposures. The product was shipped to seven states: California, Louisiana, Michigan, New York, Oregon, Texas, and Virginia.

The crisis lays bare the inadequacy of current tuberculosis testing for tissue donations in the United States, as well as a gaping regulatory hole. There is no commercially available tuberculosis test for bone tissue, which is used in spinal or dental surgeries repairing damaged bone. Even if that test existed, neither the FDA nor the American Association of Tissue Banks require companies to test their donor materials for TB.

“The FDA routinely reviews current approaches regarding screening and testing of HCT/P [Human Cells, Tissues, and Cellular and Tissue-Based Products] donors to determine what changes, if any, are appropriate based on recent technological and evolving scientific knowledge,” FDA spokesperson Carly Kemper told STAT. She declined to speculate on whether the agency might update its human tissue testing standards, which include HIV, hepatitis, and syphilis.

The risk of contracting TB through bone grafts is generally low — before the 2021 outbreak, it was last reported in the literature in the 1950s, CDC spokesperson Kathleen Conley said. Still, the freakish flukes are deadly, especially for patients already taking immunosuppressive drugs so as to not reject the needed bone implant.

“This changes people’s lives,” said Rodney Rohde, an infectious disease specialist at Texas State University. “They had to undergo massive therapy, they had to be watched for a year or two to make sure things were OK. There’s a cost to this, to both mental and physical as well as financial health.”

The recall also may come as a shock to patients and physicians who assume biomaterial has been thoroughly vetted. But the reality is that there is no simple, failsafe way to test such products for TB.

Currently, a bacteria culture test is the gold standard in all tuberculosis screening, but it’s labor-intensive and can take up to eight weeks to provide a result. Nucleic acid tests are faster and cheaper, but are less reliable and prone to false negatives. Another complicating factor is that the Food and Drug Administration has approved just three of these tests, and all of them for phlegm: a saliva-mucus mixture frequently rich with TB, as the bacteria typically settles in a patient’s lungs. Phlegm, also known as sputum, is far more difficult to collect than blood or urine.

“To put it colloquially, sputum is kind of a disgusting substance,” said Adithya Cattamanchi, a TB diagnostics researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. “It doesn’t induce pleasure for anyone to produce or for a lab person to work with.”

After the 2021 outbreak, which harmed patients and led to a flurry of lawsuits, Aziyo decided to develop its own nucleic acid test with outside experts. According to a CDC report published in The Lancet, neither the donor nor the tissue sample were tested for tuberculosis before the 2021 outbreak. Aziyo did test the tissue in the latest outbreak, but the company said the samples were negative for TB.

“Our investigation has involved additional testing on the donor lot in question through multiple independent labs and in each instance, MTB has not been detected in the donor samples,” the company said.

But lab-developed tests like Aziyo’s are outside the purview of the FDA, making it almost impossible for the public to know if the diagnostic actually works.

“We have no idea whether that assay was validated, or the extent to which it was validated,” said Cattamanchi. “There are commercial tests that are valid to use with bone tissue, but the problem is that they’re not FDA-approved for that indication.”

Tuberculosis is a nasty but largely-forgotten disease in the U.S., where there are fewer than 10,000 cases per year, though the condition remains more prevalent in southeast Asia and Africa. Despite great need, there’s little investment in tuberculosis research or tests for the bacterium.

“It’s a disease of the poor and vulnerable globally,” said Claudia Denkinger, head of the infectious disease division at University Hospital Heidelberg. “There has been more investment recently through the Gates Foundation and other global funds, but it’s still vastly insufficient.”

Cattamachi pointed out that companies developing tests, both commercial and lab-developed, may not want to go through the difficult and expensive process of obtaining FDA approval, especially for relatively small use cases like TB bone tissue testing.

There is also a question of whether bone tissue donations should be more aggressively screened. The American Association of Tissue Banks released a more stringent list of donor screening standards on Monday in response to the second Aziyo outbreak. All AATB-accredited tissue banks must reject live tissue donors who had a history of TB infection, exposure to TB in the past two years, chronic kidney failure, a solid organ transplant, or were older than 65. The group also recommended that companies avoid donors who traveled to countries with high TB levels, who were homeless, or who were incarcerated.

Barmak Kusha, a disease control expert who recently served as infection prevention director at HCA Florida Trinity Hospital, said cracking down on donors is a crucial first step for Aziyo Biologics and other companies, particularly given the imperfections of testing.

“TB inherently is a slow-growing organism, plus any substances that may have been added, chemical or antibiotic, to the graft would have slowed down their growth to almost zero,” Kusha said. “It would have been very difficult to detect even with very advanced diagnostic techniques.”

Cattamanchi and other experts hope that the recent outbreak will at least light a fire under the FDA and device manufacturers to invest in stronger TB tests and regulations — and to realize that doing nothing to mitigate the risk is not an option.

“We’ve been playing a little bit of Russian roulette just because TB is uncommon,” Cattamanchi said. “We’re not doing anything to reduce the risk of TB being in these tissues right now.”