The Cast of Seinfeld (Photo by David Turnley/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

After learning that her favorite prophylactic is going off the market, Seinfeld’s Elaine Benes had to decide which potential partners were “sponge-worthy,” even putting her new boyfriend through what resembled a job interview to see if he was up to her new sexual standards.

While the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic is hopefully behind us, new variants continue to spread, with news sources reporting this week that Jill Biden and Whoopi Goldberg have come down with the virus. Given the ongoing threat of Covid-19 and other infectious diseases, we all face a new kind of worthiness judgement, a decision about who is “contagion-worthy”: who should we hug, kiss and socialize with given the risk that they harbor a dangerous microorganism?

According to psychologists, people have “behavioral immune systems” to guide their judgements about who is worth avoiding because they might be contagious. Sometimes this metaphorical immune system picks up on obvious signs of infection—an oozing rash, a swollen pustule. Other times, it detects other cues—disheveled hair or stained clothing, perhaps. Yet other times, people have little to go on in predicting whether another person might be contagious. So how do we decide whose microorganisms to expose ourselves to?

I recently came across a 2020 study (I know, I’m behind on my reading) that answers this question. A team led by Joshua Tybur measured how willing people would be to expose themselves to someone else’s germs: the likelihood they would touch the person’s used handkerchief, for example, or share the person’s deodorant stick. (Gross, right?)

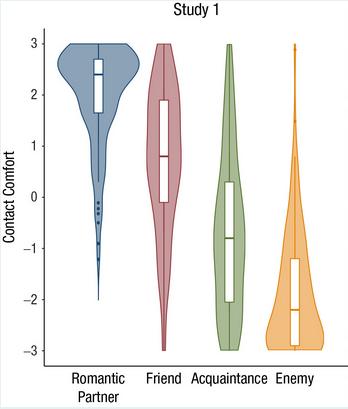

Here is a picture showing their results. On the left, the plot shows high willingness (dare I say eagerness) to share germs with romantic partners (a very different decision, of course, than being willing to use up a scarce sponge with them). On the right, it shows a strong disinclination to expose oneself to the germs of an enemy.

Comfort with Infection0risky Contact

Perhaps you are not surprised that people are more cautious about the germs of their enemies or acquaintances than of their friends. But keep in mind that there is no reason to think enemies have more or less risky germs than friends or lovers. Nevertheless, to many people, the germs of enemies and strangers feel more disgusting than the germs of close friends, this sense of disgust motivating us to avoid contact with those people’s microorganisms. In addition, I expect we let our guards down when it comes to the risk of contagion from friends, because we don’t perceive their microorganisms to be particularly icky.

I am not suggesting we should shut ourselves off, bacteriologically or virologically speaking, from close friends. But I am saying that, when it comes to sharing deodorant sticks (and who doesn’t do that on a regular basis?), your enemy’s armpits teem with just as many contagious organisms as your partner’s.