Oct 30 (Reuters) – Treasury market participants expect U.S. regulators to soon finalize a major rule aimed at reining in debt-fueled bets by hedge funds and bolstering financial stability. They worry it could also reshape the industry and create new problems.

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission rule, which was first proposed in September last year, would force much more of the trading in the $25 trillion Treasuries market, including a market for short-term financing called repurchase agreements (repo), to central clearing. A central clearer acts as the buyer to every seller, and seller to every buyer.

Market participants widely expect the SEC to finalize the rule within weeks, perhaps as soon as mid-November, according to trade group SIFMA and half a dozen banking and hedge fund industry sources.

But crucial details are unclear, including whether the SEC would want the industry to shift to central clearing in one go or allow it to do so in phases, and how much time the industry would have to implement it, the sources said.

The rule would come as other regulations in recent years have seen banks pull back as intermediaries from the Treasury market, causing some of the issues that regulators are trying to fix. The industry fears central clearing, if not done right, could undermine that goal: it will increase costs, which would risk more traders withdrawing.

How it will shape the industry is not fully understood. In recent months, for example, JPMorgan Chase (JPM.N) has reduced its position in the section of the repo market where the SEC wants banks to do more business, financial statements show. But custody banks such as Bank of New York Mellon (BK.N) and State Street (STT.N) are doing a lot more business, the disclosures show. The divergent approach has not been previously reported.

The rules would affect other market participants as well. How they are shaped could determine whether the few remaining independent brokers in the market survive.

Some of the hedge funds that borrow most heavily to take advantage of small differences in Treasury prices could find the trade is no longer profitable and stop.

“It’s very much a big bang approach,” said Rob Toomey, SIFMA’s head of capital markets, referring to the SEC’s rule. “There are costs embedded in this. Who bears those costs remains a big question.”

SIFMA, which has lobbied the SEC, expects the final rule next month, ahead of a Treasury market conference on Nov. 16.

The SEC declined to comment. SEC Chair Gary Gensler has previously said the rule-making process generally takes 12 to 24 months.

JPMorgan and BNY declined to comment. State Street did not comment.

NEAR MISSES

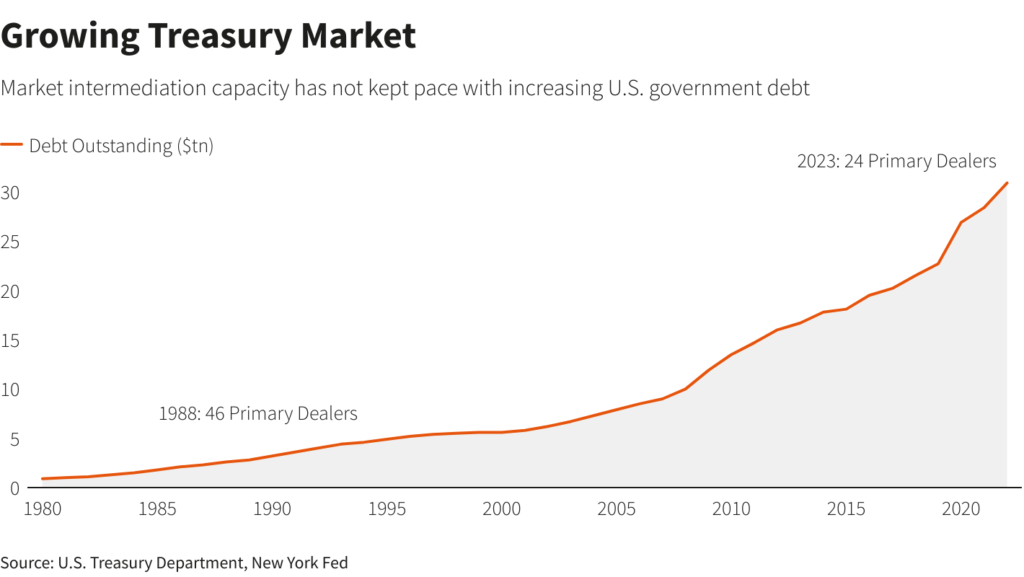

Treasury markets underpin global finance, but the foundation is cracked. U.S. government debt has ballooned in recent years but buyers have dwindled.

Banks have cut their exposure as higher capital requirements have made trades less attractive. Hedge funds and other proprietary traders have stepped in, but they can take on a ton of risk and pull back in times of stress.

There have been near misses, most recently in March 2020, when Treasury markets seized up at the height of the pandemic, forcing the Federal Reserve to step in to prop it up with emergency measures. Many experts now expect some of those to become permanent market features.

The scare prompted U.S. regulators to launch a review of market functioning. The SEC rule would be the most significant regulation so far to come out of that review.

There is broad consensus on the need for Treasury market reform, including the benefits of central clearing — even among the industry sources interviewed for this article. Most of them requested anonymity to speak candidly about the situation.

“It is going to improve financing and reduce the risks for turmoil in the U.S. Treasury market,” said Yiming Ma, an associate professor at Columbia Business School. “A lot of the worries in the market are, how do we get there? And in the process of getting there, are we going to lose something else?”

“It depends a lot on how this is implemented. What are the associated implementation costs and compliance costs?” she said.

SOMETHING IS COMING

What those costs are and how they will manifest is unclear, the industry sources said.

In the repo market, for example, where investors borrow cash for the short term against treasuries, most of the trading is done bilaterally between brokers and customers, like hedge funds. The SEC rule would force the banks to move that to central clearing.

But hedge funds do not have access to the market’s central clearing agency, a unit of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. That means banks would likely have to use their membership to give clients access through a mechanism called sponsorship. The process entails costs, which the banks will have to decide whether to pass on to their clients or not.

Those costs have meant that JPMorgan has reduced its positions in sponsored repo in recent months, with some of that trading moving to bilateral trades, according to its financial statements and one of the sources.

In contrast, BNY and State Street have increased their presence. Data is scarce, but financial statements hold some clues. Banks use an accounting process called netting to cancel out some of their lending and borrowing activity in the cleared market. Netting has grown dramatically for the custody banks.

For BNY, for example, netting in the sponsored repo market rose to $126 billion in the third quarter, up from $35 billion in the same period last year.

SIFMA has been asking the SEC to give the industry three to five years to implement the rules. Toomey said they currently expect the SEC might give two. Wall Street has started making some preparations but it’s early days.

“The working assumption is, something’s coming. What its scope is, we don’t know,” Toomey said.

Reporting by Paritosh Bansal; Editing by Anna Driver

: .