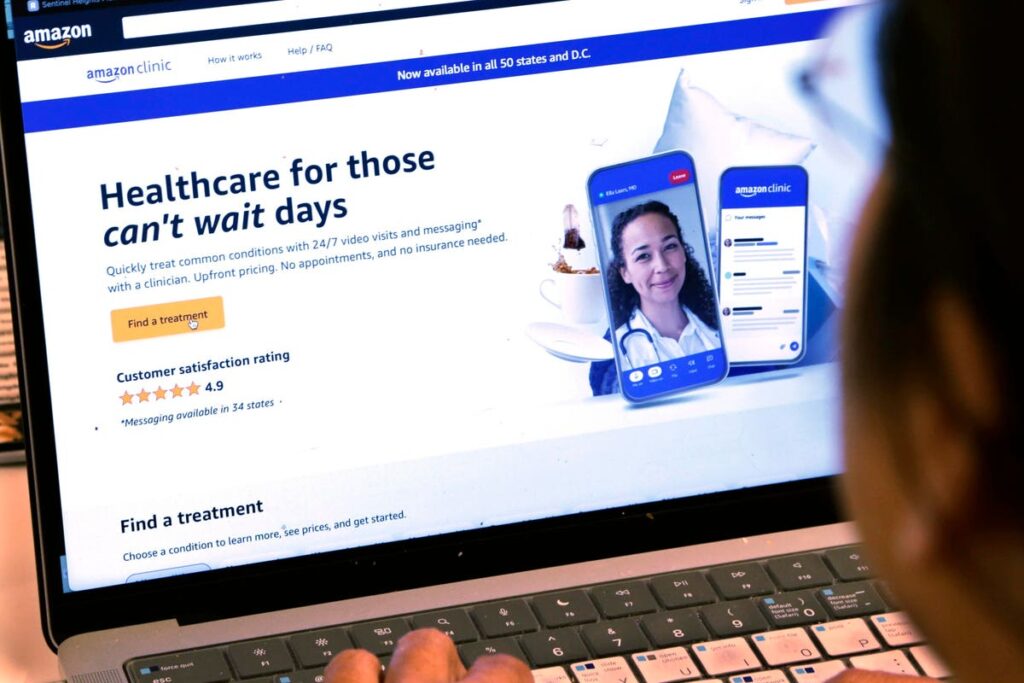

A page from Amazon’s clinic site is shown on a laptop in New York on Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2023. (AP … [+]

Amazon recently announced that their virtual care service platform, Amazon Clinic, will expand to all 50 states and the District of Columbia. This latest move is part of Amazon’s relentless foray into healthcare delivery, as they continue to strategically chip away at a market that is dysfunctional and fundamentally broken.

The e-commerce giant has a long track record of disruption, and this latest move further demonstrates that a more convenient, accessible, affordable, transparent–and, most importantly, patient-centric–healthcare model is possible. Meanwhile, moves by Amazon and other retailers into this space have left traditional provider executives quaking in their boots. And they have every reason to be concerned.

In December, a survey of health tech experts found that a majority of respondents (52%) believed Amazon would be “the biggest threat to health systems’ core business by the end of 2023,” followed closely by CVS (47%), Walmart (36%) and Walgreens (27%). This prediction will likely play out as expected as Amazon’s influence continues to swell.

Amazon Clinic will now give patients nationwide the ability to connect 24/7 with a clinician to treat symptoms for more than 30 common ailments. High blood pressure, high cholesterol, asthma, migraine, acne and even smoking addiction can now be assessed and treated with a few clicks. Amazon Clinic’s Chief Medical Officer and General Manager Dr. Nworah Ayogu said that in taking this approach, they are removing barriers “by helping customers treat their everyday health concerns wherever they are, at any time of day.” In addition, “they can see the cost before they start the visit.”

The latest announcement comes on the heels of Amazon’s strategic $3.9 billion acquisition of One Medical. As I wrote at the time of the deal’s closing, this blockbuster deal is a potential game-changer. It gives Amazon the last piece of the puzzle they need to deliver fully integrated primary care nationwide–a brick-and-mortar presence.

Amazon’s success story can be traced back to its ability to anticipate industry shifts. It has built a diversified portfolio of services in pursuit of a new healthcare model by combining the infrastructures of different organizations they felt had something competitive to bring to the market. With nearly 170 million Amazon Prime subscribers and counting, Amazon has the potential to improve health outcomes for countless individuals.

While some questioned what the future of Amazon Health would be like after Jeff Bezos stepped down as its CEO in 2021, I opined that it did not stall Amazon Health’s momentum. Other company executives were the ones making systematic investments, which is bearing fruit today.

Simply put, all of this has been happening because the Amazons of the world could see around the bend in the road to what many in healthcare delivery simply could not: the need to fundamentally overhaul a delivery system that is fragmented, confusing, opaque, expensive and sometimes downright dangerous–and all underscored by a perverse fee-for-service (FFS) payment model. It was all predictable.

In my 2016 book, Bringing Value to Healthcare, I forecasted the inevitable. Today, new players, including Walmart, Walgreens, CVS and other entities that were not operating in the traditional healthcare space, are creating dramatic disruption by taking advantage of the industry’s inability to see itself operationally in a fundamentally different way. Those of us who have been watching saw this storm brewing long ago.

I envisioned a day when a shift in care delivery from the primary care doctor’s office to walk-in clinics, would dramatically pick up speed. As I also discussed in my book, more and more people would be focused on convenience, and would begin to trust nontraditional settings for blood pressure and other screenings, flu shots and other immunizations.

Screenings, in particular, have led to earlier diagnoses and referrals to specialists. And by tying in access to low-cost generic medications, these players have also disrupted traditional pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) who, in retrospect, have been a bridge between the old and new model of healthcare. In turn, hospitals would be left to focus on what they do best: acute, complex intervention. In essence, they do not have to be “all things to all people.” However, despite the repeated warnings that the traditional healthcare delivery system is in critical condition, many traditional healthcare providers have scoffed at non-traditional entrants.

As we noted in our Numerof & Associates 2022 State of Population Health Survey Report, some delivery organizations, instead of embracing a new patient-centric model, have turned to familiar protective strategies, such as reducing direct competition through acquisitions or lobbying aggressively to create regulatory barriers through trade groups.

In 2007, a group of American Medical Association (AMA) doctors went so far as to urge the group to ban retail health clinics, with one physician saying “there is no more urgent issue than this for the AMA.” He added that if the Association fails to act, “in five years, the chairs [at the AMA] meeting will be filled with representatives from Walgreens, Wal-Mart and other retail outlets.”

The traditional healthcare industry’s concerns with a new disruptive model are ostensibly about a lack of data privacy protections and a deterioration in quality, coordination and continuum of care. But for an industry that has historically been loath to change, these concerns must be balanced against the serious underlying flaws of the current system. As Amazon’s Ayogu put it, “the reason why they’re [patients] [are] not healthy is because the health system has all these barriers, so whether that is cost, confusion … some are societal, some within the health-care system, so that’s really on us to remove those barriers and think through how we do that.” He gets it.

For all their midnight fretting, traditional health care providers miss the larger point. If they were doing a better job of meeting patients’ needs, consumers wouldn’t be seeking out these alternatives. A recent survey found that nearly 60% of Americans “are likely to visit a local pharmacy as a first step when faced with a non-emergency medical issue,” with a majority of Gen Z (56%) and Millennials (54%) reporting getting care at a local pharmacy in the past year.

Getting to an entirely new patient-centric model at scale is hard work, and all stakeholders–from manufacturers and providers to payers and consumers–have a collaborative role to play in fixing problems they have collectively created. And while Amazon’s ability to exact change in other, more complex areas of care remains uncertain, they and other forward-thinking players are setting a new baseline for what should be normative in primary care.

If provider organizations want to be innovative, nimble, consumer-savvy and customer-responsive, they can start by changing the way in which their practice is run, so those other options don’t look so attractive. This means putting an end to business model desperation–searching for every last nickel and dime–and stepping back to conceptualize how to do things differently.

All stakeholders in healthcare delivery say they want “better health outcomes at lower cost.” That’s encouraging but the question is–at what price?