Endometriosis, a common gynecological condition, is one of health’s great mimickers. It can manifest as a variety of painful symptoms but evade detection on scans and examinations. And for the estimated 10% to 15% of women with endometriosis, it can take over a decade to get a diagnosis.

Part of the lag is because researchers still don’t know exactly how endometriosis occurs, except that the flow of menstrual blood backward through the fallopian tubes plays a role in some cases. However, mounting evidence suggests bacteria is involved, too.

In a study published in Science Translational Medicine on Wednesday, researchers from Nagoya University documented how Fusobacterium might spur the development of endometriosis.

The researchers analyzed tissue samples from 79 women with endometriosis, and 76 without, all of whom had surgery at Nagoya University Hospital and Toyota Kosei Hospital in Japan. They found that 64% of patients with endometriosis had Fusobacterium in their uterine lining, versus fewer than 10% of women in the control group. Vaginal swabs from these patients showed the same thing — a much higher prevalence of the bacteria in those with endometriosis than those without the disease.

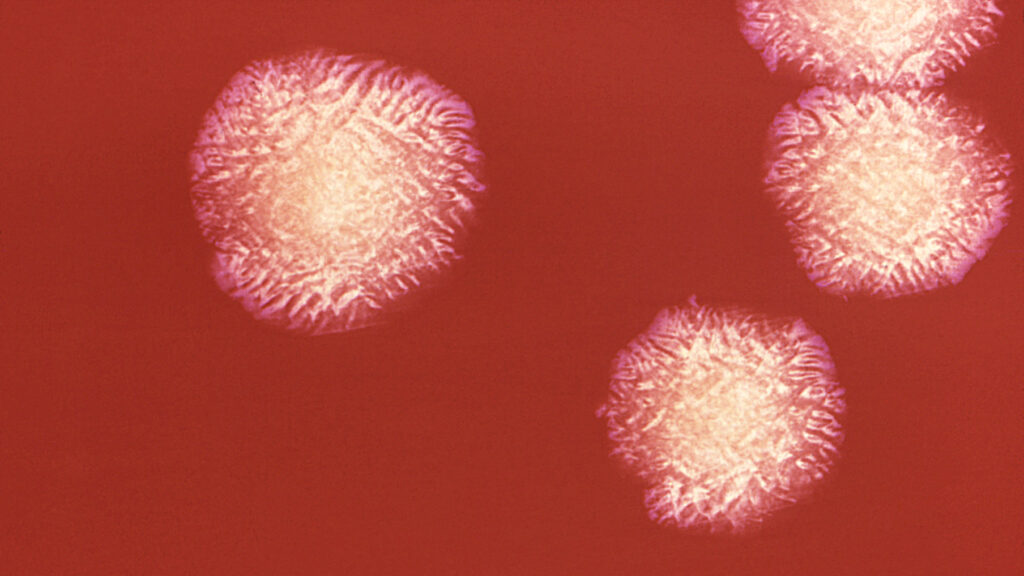

The mere presence of Fusobacterium, a genus with cells that look like double-ended pencils, isn’t surprising. These are naturally occurring bugs often found in the microbiomes of the mouth, gut, and vaginal region. And while they rarely cause serious infections, recent studies have linked Fusobacterium to certain inflammatory conditions, such as colorectal cancer and the severe gum infection periodontitis.

The uterus has been thought to be a nearly sterile environment, with far less bacteria than the vagina or other parts of the body. But Fusobacteria are still found there, and might be more pervasive in people with endometriosis, some studies suggest.

Yutaka Kondo and his colleagues wondered how this bacteria might be driving endometriosis.

Their analysis suggests Fusobacterium infection could be triggering structural changes that are a signature of endometriosis, like the distribution of endometrial-like tissue outside of the uterus. Via “retrograde menstruation,” blood and tissue flow out into the abdominal cavity up through the fallopian tubes. But they think it is the bug’s presence in those endometrial cells that causes trouble. “The key event is Fusobacterium infection,” said Kondo, a physician and researcher in the division of cancer biology at Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine.

Fusobacterium rings a metaphorical alarm that awakens connective tissue cells, called fibroblasts, and makes them stickier and more prolific. That alarm is transforming growth factor beta, a well-established endometriosis culprit that has the power to turn chill, non-dividing fibroblasts into superpowered transgelin (TAGLN)-positive myofibroblasts. These cells are great at reproducing and clumping together.

A specific type of Fusobacterium, F. nucleatum, could also be triggering an innate immune response around endometriosis lesions — the tissue growing outside the uterus — which produces even more transforming growth factor.

Rama Kommagani, one of the first researchers to establish a link between microbiota and endometriosis, said the interaction between Fusobacterium and transforming growth factor beta is the most interesting part of the new paper. “The role of that in converting the fibroblast cells into myofibroblasts is very compelling,” said Kommagani, an associate professor of pathology and immunology at Baylor College of Medicine.

Kondo and his team took their findings one step further, introducing F. nucleatum bacteria into the uteruses of mice. Although, importantly, mice don’t have menstrual cycles or develop endometriosis at random, Kondo’s group was able to confirm the reach of Fusobacterium in their rodents.

Then, they cured them. By using transvaginal metronidazole and chloramphenicol, antibiotics that can kill F. nucleatum, the researchers were able to tone down the whole ripple effect — from bacterial infiltration, to transforming growth factor (the alarm) and the juiced-up myofibroblasts, and endometriosis lesions. “The data was compelling for the particular microbe they tested,” Kommagani told STAT. “However, I think it should’ve been done in germ-free mice,” without a microbiome. That way, researchers could just observe the Fusobacterium and its effect, he said.

Other research in mice, including by Kommagani’s team, has also shown that metronidazole, typically used to treat the sexually transmitted infection trichomoniasis, curbed endometriosis. That work then led to a small, ongoing clinical trial at the University of Louisville studying the effect of metronidazole for post-operative pain after endometriosis surgery.

Kondo thinks metronidazole, also called MZ, could be an attractive tool. “If the drug is appropriately used, the adverse effect is quite limited,” he said.

However, broad-spectrum antibiotics that target a vast array of pathogens also wipe out bugs that are beneficial to the microbiome, so could have unintended effects. “And also, long term, we cannot use antibiotics because of the resistance,” Kommagani said. Antimicrobial resistance has been a growing problem for decades, as bugs outmaneuver and evolve more quickly than humans can develop new antibiotics. Because of this, experts recommend the medications be reserved for urgent cases, and tailored as best as possible to the pathogen causing a person harm.

So while antibiotics might not be a permanent solution, Kondo’s work raises the possibility that other therapies might be. For example, if a drug could block the myofibroblast-activating cascade, that could go a long way, Kommagani said. Endometriosis is in dire need of treatments.

For over half a century, people with endometriosis have been put on the birth control pill, even though it doesn’t really help, for lack of better therapeutic options. The most effective strategy to date is surgery to remove excess tissue, but people often redevelop endometriosis. Left untreated, the condition comes with a heavy cost: Many people report severe and excruciating periods, painful sex, and infertility, among other disabling symptoms.

Researchers still don’t know exactly how Fusobacterium enters the endometrial tissue, or what makes some people more susceptible to infection than others. It’s possible that the bacteria is sexually transmitted, though it could also just go from mouth and throat to uterus through the bloodstream. Kommagani also wants to know the mechanism by which Fusobacterium enters endometriosis lesions and turns on the harmful fibroblasts, since it wasn’t clearly delineated in the paper.

But the new study gives insight into what might be causing at least some cases of the complex condition that is endometriosis.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.