For a person with celiac disease, eating a bagel goes something like this: chewing and savoring, the flavor of the high-gluten bread made ever more delicious by its forbidden nature, by knowing there will be hell to pay.

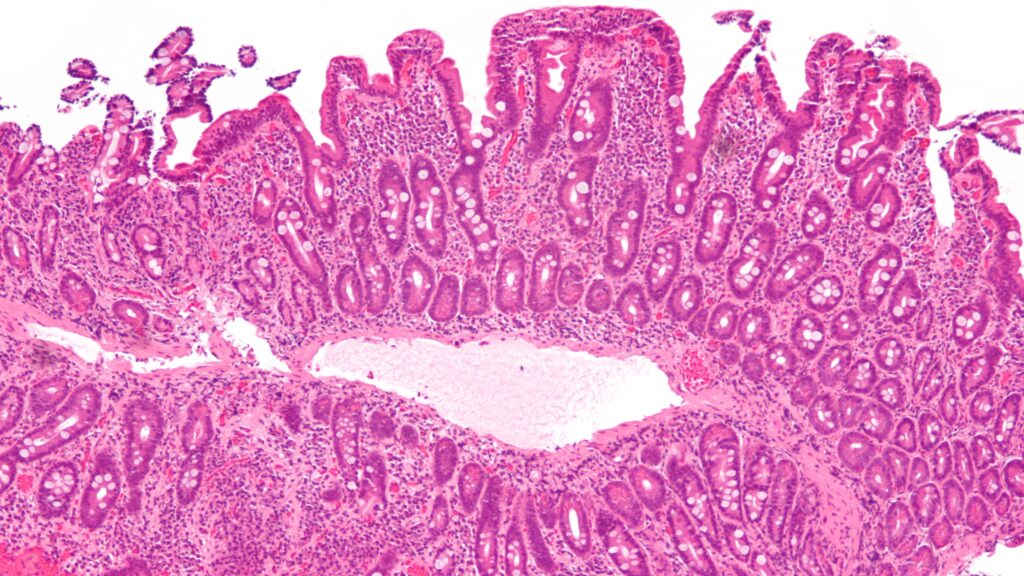

Then, the bagel is broken down, separated into the digestible and the not: Parts of gliadin, a protein found in gluten, stay in the gut. And that’s where things start to go awry. Immune cells detect the presence of gliadin and freak out, activating a full-blown inflammatory response that leads to pain and intestinal damage.

Exactly how that damage occurs — and why it happens to only about 1% of the population, when so many more people are genetically at risk for celiac or mount a milder immune response — has been unclear.

But new research published in Science Immunology on Friday offers a possible explanation for how T cell tantrums lead to intestinal lesions, and hints at a process that might be at play in other autoimmune conditions. As an autoimmune condition of the small intestine, celiac can cause an array of symptoms, from poor absorption of nutrients to chronic diarrhea and fatigue, brain fog, osteoporosis, and more.

The paper’s senior author, gastroenterologist Arnold Han, has studied celiac for over a decade. And he watched as researchers came to the realization that CD4+ T cells alone weren’t enough to cause intestinal damage. Instead, the field began noticing the involvement of intraepithelial lymphocytes, or T-IELs, a population of T cells in the GI tract.

In celiac patients, some of these T-IELs were getting activated even though they don’t recognize and attack gluten the way other T cells do. The T-IELs have what are called natural killer receptors, which alert them to a problem — say, a virus or tumor — that needs to be dealt with.

Models of celiac have mostly suggested that the original scuffle, between gliadin and tantrum-throwing CD4+ T cells, was triggering inflammation and that, in turn, activated the T-IELs to harm the intestinal lining. But the latest study offers a different idea. “One thing that we found, a little bit unexpectedly, is that these NK receptor-expressing IELs are really activated very, very fast and deliberately by gluten,” said Han, an assistant professor in the department of medicine and in microbiology and immunology at Columbia University.

Ludvig Sollid, a prominent celiac researcher at Oslo University Hospital in Norway, said the study offered a comprehensive characterization of different T cells involved in the disease, and underlined a question: “Whether CD4+ T regulatory cells in celiac disease still have a function in the disease pathogenesis.” To him, the most interesting finding in the paper was that about the toxic duo of natural killer receptors and T-IELs.

Han is no stranger to a little controversy. As a postdoc in the lab of another celiac expert, Mark Davis at Stanford, Han suggested that various kinds of T cells were activated at the same time when a person with celiac consumed gluten. His data showed CD4+ cells in the blood, but also tumor-surveilling CD8+ T cells, and unique gamma delta T cells. But that model “was kind of discounted by the field,” he said, and the T cells were dismissed as normal, recirculating presences — not part of a systemic inflammatory reaction caused by gluten.

His new paper doubles down on the idea that several kinds of T cells are simultaneously riled up by gluten, and that they are not present just as a result of recirculation. The data, based on small intestine biopsies from 37 patients at different stages of disease and 17 healthy controls, suggest T-IEL cells shift from anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory, and they go on to kill intestinal tissue. “That part was actually kind of surprising,” Han said.

As he describes it, there’s been a mostly friendly thumb war going on between celiac researchers for decades. Are T cells turned on at the same time? How important is the CD4+ reaction? Everyone builds on each other’s work and inspects new possible explanations. In the last few years, some in the field have thought tumor-fighting CD8+ T cells come in to suppress the disease-causing immune response of CD4+ cells. But Han’s data strongly argues against that, instead pointing to CD8+ cells as a destructive force. “It kind of goes against these other, very provocative models that are being proposed,” he said. “This is something to be sorted out by the field. And we do point out that the models are not mutually exclusive.”

The mechanism of how the immune system is triggered by gluten — and how it leads to the kind of intestinal damage that severely impacts some people’s lives — matters because it could point the way to a treatment. “We know that these bad, probably tissue-damaging populations, they’re present in patients with potential celiac disease who don’t have damage,” said Adam Kornberg, a Ph.D. candidate who was first author on the paper. “We have some ideas as to why they’re not causing tissue damage there. But those would be totally good targets for a therapy to hold these people in check for their life, so they never progress to patients with actual tissue damage.”

And learning how T cell-driven autoimmunity works in celiac disease, in which gluten is a clear and controllable trigger, could provide valuable insights into how other autoimmune conditions occur, Han said.

There’s no shortage of follow-up questions to investigate: How exactly are all these immune cells getting activated by CD4+? And what purpose do these T cells have in normal biology? How are they being co-opted into attacking healthy tissue? Given how many people have potential celiac disease and no gut lesions, Kornberg suspects there is a “last little boost” that drives the T-IELs to destroy the intestinal tissue. But more research will be needed to figure out what exactly that final push is.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.

Correction, 5:56 p.m., July 14: A previous version of this story misstated Adam Kornberg’s first name.