CHICAGO — Abdullah Hassan Pratt is giving a tour of a sheep heart that sits, heavy and sodden, in his hand. Dressed all in black, with his Jordans and easy manner, Pratt doesn’t look all that different from his audience: dozens of teenagers from this city’s roughest and poorest neighborhoods.

One student raises a tentative hand, utterly confused by how blood travels through the heart. The grayish organs lying limp on tables in front of the students look nothing like the crisp diagram marked with bright red and blue arrows projected on a screen behind Pratt in the high-tech simulation center at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. “Look, all you need to know is where you are,” says Pratt. “If I dropped you off at Checkers, you’d know how to get to school, right? It’s just like that. So start at the superior vena cava, and give me the pathway.”

The student nods. Around the room, teens poke fingers into dissected hearts, undeterred by the overwhelming pickle-like smell of formaldehyde. One young woman takes a selfie, a heart clutched tight in her blue-gloved hand. Some of these students are the best and brightest from their schools. Others are kids who rarely get a second, or even a first chance, because so many have already given up on them. Pratt hasn’t. He wants them to be doctors — like him.

Pratt grew up like many of these students, in a predominantly Black neighborhood on this city’s South Side, just a few miles from the University of Chicago medical complex where he now works as an ER physician. Playing football in college was one route to professional success, as was a medical pipeline program like the one he now runs for Black and brown kids who don’t otherwise have a clear path into the field, and because of where they live, face a high risk of homicide themselves.

Chicago is often called “Chi-raq” for a reason. A recent study shows young men in the city’s roughest ZIP codes are twice as likely to die than soldiers who were deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. The grim headlines roll out with depressing regularity. “17-year old among 7 killed.” “16-year-old fatally wounded, at least 4 other teens shot.” “13-year-old among 8 fatally shot in Chicago weekend violence.”

In a seven-year period, nearly 1,700 children under 17 were shot in Chicago, and 174 were killed. One in five teens says they’ve witnessed a fatal shooting. All that violence and daily stress takes a toll, leaving many kids traumatized, hopeless, and sometimes the ones doing the shooting.

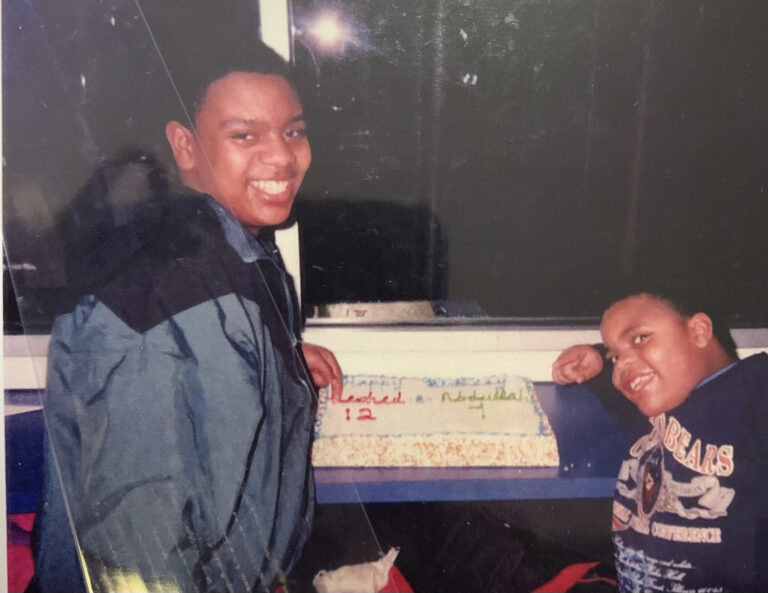

Pratt knows their despair. Health disparities — life expectancies for Black men in Chicago are 10 years lower than those for white men — are not just the stuff of dry statistics and academic studies for him; they are his life. His dad died too young, as many here do, of cardiovascular disease at the age of 64. He recently lost two friends, one just 39, to colon cancer. In 2012, his older brother Rashad died at age 28, gunned down just a few hundred feet from the family home. The killer has still not been found. Pratt had just finished his first year of medical school.

“That was the turning point for me,” Pratt said. “I decided I wasn’t just going to be a good doctor, but a great one.” His mentors didn’t offer him condolences after the murder. Instead, they challenged him. “You have to use this to make sure other people don’t suffer,” they told him, “Let this be the torch you carry.”

Pratt, 34, idolized his older brother and still remembers what Rashad said to him when he’d gotten his first high-rise apartment on the shores of Lake Michigan, a major step up from the family home. “This is nice, but none of it means shit if you can’t help people from where you came from,” Rashad had said. “Then you’re just another hypocrite.”

It isn’t only Rashad that Pratt has lost to shootings. Three years ago, his high school teammate Damon Chandler was shot to death while driving. Two years ago, his best friend from childhood, Arthur Owens, was killed while stepping out of a car. He sees more of the same at work. He’s cradled the heads of teenagers of neighbors and coworkers when they die in his ER. This year’s MLK weekend was especially deadly in Chicago. Six people came in DOA on one of Pratt’s night shifts while a steady stream of others were treated for gunshot wounds. “It was really bloody,” said Pratt. “I didn’t sit down the whole night.”

His efforts to inspire local kids — this program, as well as free sports physicals and talks he gives in classrooms where students have recently died — have gained him the respect of his mentors, accolades from medical leaders across the country, and the attention of the media. He’s considered a Chicago hero. He should be on top of the world. But he’s not.

It’s not easy to tell — Pratt, who generally refuses to wear the traditional white doctor’s coat because of the negative connotations it has for many Black people, and tells everyone to just call him D — has the same easy laugh he’s always had, a smile so wide it’s visible across a room, and the stamina you’d expect of a former offensive lineman. He can tell stories for hours. But underneath it all, the big man is struggling.

It’s been a hard journey — and it’s far from over. It’s exhausting to straddle two very different worlds: the Black one he comes from and the overwhelmingly white world of medicine he’s entered. Even with a physician’s salary, structural racism throws up roadblocks to upward mobility; for a long time, redlining and discrimination by banks frustrated his quest to buy a home for his family.

On top of it all, there’s the unceasing death on his streets and in his ER. “I’m the one that can’t get the screams of those mothers out of my head,” he said. He’s tired, financially stressed, and at times, overwhelmed with the demands of shouldering so much. Despite his commitment to these streets and neighborhoods, despite all his work with young people, and despite the promises he made to his brother and to himself, the particular beacon of hope he provides here on Chicago’s South Side may not last if something doesn’t change soon. Says Pratt: “I give it a year.”

Black doctors, deservedly so, are the pride of their families and communities and stand as inspiration for those who might follow their difficult paths. Their challenges can include getting the top-notch science and math education they need to be competitive for college and medical school, widespread discrimination during their training, and, when they finish, crushing debt. These are struggles their white physician colleagues may have little idea about. But Pratt is open as a book.

Pressures are different for doctors who come from neighborhoods like his, he says. A lot of people ask him for money, assuming he’s flush. “When you’re successful among your peers, everyone wants you to be the godfather — literally,” he said. He helps where he can, especially kids who lost a parent in a shooting, but there’s not a lot to go around. He and his wife are raising two young children in an expensive city on a single income while he tries to pay off more than $300,000 in student loans.

Pratt had advantages growing up that many in his community did not. He was raised by both of his parents, who were middle-class and successful — until misfortune struck. His mom, Melva Pratt, earned an MBA at Texas A&M and went on to work as a teacher and community organizer. His dad, Edwin, was a psychiatrist, a trailblazer in a field where even today just 2% of practitioners are Black. The family lived in a part of the South Side with better than average schools and a lower crime rate called Pill Hill, after the large number of Black doctors who lived there in the ’70s. The Pratts were one of few families to have an Encyclopedia Britannica set at home.

But when Pratt was in elementary school, his father lost his medical license after disciplinary actions and the family’s finances took a hit. They were not starving, but definitely poor, he said. He didn’t have Jordans like many of his classmates. Any brand name clothes he wore came from discount stores.

What his parents did spend money on was enrichment programs for Pratt at Chicago’s science landmarks — the Museum of Science and Industry, Shedd Aquarium, Adler Planetarium — he couldn’t get enough. He was often the only Black participant. “It told me this world was bigger than communities that were 100% African American,” Pratt said.

He dissected squid at the age of 7 and brought home award after award for his scientific prowess. At the same time, watching shows like “Grey’s Anatomy” and “ER” with his mom piqued his interest in medicine. “I know the seasons front and back,” said Pratt. But his dad, crushed by his own disappointments, didn’t encourage him.

Pratt’s route to becoming a doctor, and a program he now says changed his life, was a complete fluke. Though he could be a smart-ass, he was not a troublemaker at school. But he got called into the office one day in the fall of his senior year for having a cellphone. (He was taking the rap for a football teammate who wouldn’t be able to play if he received another suspension, he said.) The exasperated assistant principal asked what Pratt wanted to do with his life. Pratt said maybe he’d be a doctor. He was enrolled the next day in the Health Professions Recruitment and Exposure Program (HPREP), a 30-year-old effort held at medical schools around the country to draw more students from underrepresented groups into medicine.

Edwin McDonald, a medical student at Northwestern who was running the HPREP program there, still recalls first impressions of Pratt from two decades ago. “He seemed like a cocky high school football player,” he said. But then McDonald saw how seriously Pratt took his education. “I had a feeling he was going to succeed,” said McDonald, now a gastroenterologist and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago who continues to mentor Pratt. “Fast forward: He did.”

Pratt had known he wanted a career with the University of Chicago ever since he stumbled onto its shockingly beautiful campus, an oasis amid much rougher neighborhoods, while riding his bike as a kid. After HPREP, he decided Chicago’s Pritzker medical school would be his goal. Realizing it would take top grades, he kicked into gear. Five years later, he was in.

Pratt grew up in awe of his brother Rashad. He was five years older and Pratt’s protector. If Pratt got hassled for being in the wrong neighborhood, or on the wrong block, the tension would resolve suddenly once the accosters learned he was Rashad’s little brother. “It would change the whole demeanor.” he said. “They’d say, ‘You got to stay away from this block, it’s not safe. Can I get you a ride home?’”

When some older kids kicked Pratt’s best friend off his bike and stole it, Pratt assumed it was gone forever. “Rashad asked what happened, walked off, and literally came back riding the bike,” he recalled.

Rashad’s reputation — as a fearless protector of the neighborhood, not a gang-banger — shielded his brother, allowing him to go to science camp and play high school football. “He was the reason I was free to become who I am,” Pratt said. “A lot of young men get tied up in things they shouldn’t because they’re trying to prove they’re not the weakest guy in the neighborhood. It’s not gang stuff, it’s social hierarchy, you spend a lot of time, as we say, on the block.”

His brother had similar aspirations but never had the chance to pursue them, Pratt said: “No one told him maybe it’s OK to go to school and be a geek for a bit.”

Rashad was gifted — he could fix anyone’s stereo or the electrical system in their car, Pratt said: “He had the best hands I’ve ever seen.” He took apart electronics and rebuilt entirely new systems in his basement — without any formal education.

After graduating from high school, Rashad started technical college but never finished. Still, he was making something of himself. A long-haul truck driver, he had bought a few trucks of his own and was in the process of starting his own business when he was shot early on an August morning in 2012, just blocks from the family home. He had apparently confronted people who were trying to steal a car.

Rashad left behind a little girl he treasured. She’s now in high school. Last year, she was a student in Pratt’s program.

Shooting deaths are a constant here, like a steady hum. Pratt isn’t a researcher. He has no public health degree, but he’s doing what he can to change the numbers — starting with the kids who are most at risk.

On a recent Saturday, his Medical Careers Exposure Emergency Preparedness program is a whirl of activity. In one room, students are suturing cuts into thick squares of fake skin, learning how to maneuver needle drivers and carefully tie surgeon’s knots around their forceps. It’s tricky work. “I’m not lying, this is probably one of the best ones I’ve seen a student do,” James Oyeniyi, a vascular surgery fellow told Arabel Navarrete, a first-generation high school student whose family migrated to Chicago from Mexico.

With each new lesson, she was gaining confidence that she could succeed in medicine. “I’m thinking about surgery, honestly,” she said.

Oyeniyi, a Black man in an elite surgical specialty where less than 2% of practitioners are Black, said he wishes he’d had an opportunity like this. “Seeing someone who looks like you doing something people have told you you can’t do is very powerful,” he said. “I wish I knew Black male doctors growing up.”

Pratt’s own trajectory is one reason he is so committed to taking students into his program who don’t stand out on an application, or might seem like trouble to others. He doesn’t require top grades or ask for long essays because many of the kids, particularly boys, have trouble expressing themselves on the page.

“I would have been selected against,” he said. Instead, he’s looking for the attributes he had: a spark, a desire to raise themselves up, a willingness to work hard, and a true passion for medicine.

Many of the physicians and medical students who volunteer to teach in Pratt’s MedCEEP program are inspired by him and eager to help, even if it means giving up entire Saturdays. “He’s literally from the neighborhood, he’s connected, and understands so many people in the community,” said Vivek Prachand, a professor of surgery at the University of Chicago, as he helped students learn laparoscopic surgery, encouraging them as they tried to manipulate small objects with both hands while watching only a screen. “It’s my honor to do so many things next to him.”

“I have an exam on Monday, but this matters to me,” said Alia Richardson, a Black former high school biology teacher and first-year medical student from New York who helps run the program.

A key part of the training involves learning how to provide emergency care to people who have been shot to keep them alive until an ambulance arrives. The students learn CPR and are given kits filled with tourniquets, bandages, and gels. One former student, Pratt said, used her kit a week after she’d received it to help a young gunshot victim outside her house. Such instruction is sorely needed; studies show Black and brown victims are less likely to receive CPR or other aid from bystanders.

The sad fact of Pratt’s program is that so many of the teens have had friends or family shot. “When you ask, you see every hand go up,” Pratt said. A basketball teammate of Hassan Johnson, a sophomore on a fast track in STEM, engineering, and robotics who’s now interested in orthopedic surgery, died in a shooting two years ago. He was just 15. “It has touched a lot of people around me,” he said.

Pratt talks to the students about increasing the odds of their own survival. “Don’t sit in cars, idling. Don’t go to gas stations after dark,” he tells them. “If you feel omens, maybe that’s not the right night to be out.” It’s wisdom he’s learned first-hand. “That’s the PTSD of living in these communities. You’re always doing the 360-degree turn.”

Through these hard conversations and trainings, Pratt is creating a young army that will know how to save lives — and may get interested in careers in medicine along the way. About 800 students have gone through the medical training programs since 2018, he said, and many have since become health care workers, including nurses and one who is now a first-year dermatology resident.

Others, like Haley Avila, are eager to follow their lead. A high school senior, she laughed out loud when asked if anyone in her family was a doctor. Not yet — her parents work in human resources and parts delivery. But she’s getting a leg up to reach her career goal. “I’m really aiming to be a surgeon,” she said. “I think I can do it.”

Pratt was in medical school when he got an early lesson in straddling two worlds.

For decades, residents shot on the South Side had to be transported to hospitals across the city, with some dying during long ambulance rides. University of Chicago Medicine had closed the area’s only Level 1 adult trauma center in 1988, citing high costs, and resisted activists’ calls for it to be reopened.

The lack of trauma care became a major rift, and in 2010, the shooting death of 18-year-old Damien Turner, within sight of Pratt’s home and just four blocks from the university’s medical center, galvanized the community. “He climbed in the ambulance by himself,” Pratt said. By the time he reached Northwestern, nine miles away, he was dead.

Turner, though young, was a leading community activist. At 13, he had started a group to advocate for a new trauma center. No one could say for sure if Turner would have survived if there’d been a closer trauma center, but the community was angry. Making matters worse, the University of Chicago health system was building a $700 million pavilion. “The hospital has blood-stained hands,” a pastor said at Turner’s funeral.

What followed were die-ins in the street, ugly confrontations, and debates. “U. of C. is whack, bring the trauma center back,” protesters chanted during marches. And “How can you ignore, we’re dying at your door?” Many community leaders said they’d oppose locating the Barack Obama Presidential Center in the area if no trauma center was built.

Pratt wanted to get involved with those pushing for a trauma center, but was cautioned not to by some of his teachers. Being on the wrong side could get him in trouble, he was told, or even kicked out of medical school.

“It was volatile,” said Pratt. “It was an us-vs.-them mentality. When I went to listen to the community, they thought I was a plant.” The charismatic Pratt was eventually able to navigate both sides, to explain to the community what the medical school’s issues were and to explain to his medical school what the community needed. He didn’t curb his outspoken nature or his enthusiasm for anything that would help his community heal. “The same way we attack cancer at this hospital, we should attack violence,” he said.

Pratt’s involvement in the politically sensitive battle didn’t surprise his mentor McDonald. “For him, becoming a physician was more than having the ability to treat patients. It was about taking care of the whole community,” he said. “Staying off the radar is well-known among Black physicians — it is — however there are some things that are bigger than you, and the need for a trauma center at the University of Chicago was bigger than Dr. Pratt. It was bigger than all of us.”

In the end, the university decided to build the trauma center. It’s now so well-regarded and busy treating cases of penetrating trauma that the U.S. Army sends surgeons and nurses there to train. When it opened in 2018, Pratt, then an emergency medicine resident, worked the first shift.

The University of Chicago has been a lodestar for Pratt. He grew up in its shadow, and was long drawn to its storied excellence and promise. He’s proud to be a doctor there. But this choice has cost him.

He attended Valparaiso University on an academic scholarship. When he graduated, he was offered scholarships from other medical schools but instead chose Chicago, taking on more than $300,000 in debt to do so. After his residency, he chose — how could he not? — to work at the trauma center he’d played a role in opening. But that decision has cost him too. He earns $227,000 a year, but said he would have earned nearly twice as much if he’d taken one of the many job offers he’d received from suburban hospitals.

Pratt drives a Mercedes, but it’s used. The newer family car is the one he bought for his mom. These days, Pratt does treat himself to the Jordans he never got to wear in high school. But the Louis Vuitton backpack he carries everywhere, partly because such tangible marks of success inspire many of the kids he’s trying to reach? It’s fake.

It’s not that Pratt needs to be rich. But he’d like to send his children to schools like the vaunted University of Chicago Laboratory School, which he can’t afford. He wants to own a home, as doctors do. He is surrounded by residents and fellows who come to Chicago for a few years of training and snap up nearby homes with their family’s help and legacies of generational wealth. With the rapid gentrification occurring around the new Obama center site, many of these trainees now turn a tidy profit when they leave after just a few years.

He’s happy for them. But it’s a painful reminder that many of the area’s Black residents have rarely been able to own homes, or reap wealth, from real estate in their own neighborhoods, where the vast majority of residents are renters.

Many South Side neighborhoods, like Pratt’s Woodlawn, have a history of disinvestment and landlords exploiting Black residents who had few other choices of where to live due to racial covenants that made it illegal for Black people to live in many parts of Chicago, and other discriminatory practices. But with the restoration of nearby Jackson Park, and the building of the massive Obama Presidential Center, the neighborhood’s fortunes have shifted for the better.

Banks and developers from outside the community are swooping in now that there’s money to be made, completing a cycle of what activists decry as “rape and rescue.” Driving through the streets of West Woodlawn, the change is visible: “Smart houses” are popping up on empty lots, while many of the area’s stately greystones and houses dating back to Chicago’s 1893 World Fair are being gutted and restored.

When Pratt sought to do the same — trying to buy the two-flat that contained the apartment he’d rented as a medical student from the elderly Black owner who wanted to sell to him so it would stay in Black hands — he couldn’t. For two years, he said, the bank wouldn’t appraise the property for what he needed to obtain a loan even though neighboring properties in worse condition were being valued at much higher amounts for developers, he said.

Studies show this “race appraisal gap” — a systemic undervaluing of real estate in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods and of properties being bought or sold by Black or Hispanic owners — has increased in recent years, as has frustration. “For a young physician, living on the South Side of Chicago who makes six figures-plus, to not be getting a loan, we shouldn’t even be talking about this,” McDonald said.

It took Pratt’s broker Don Robinson, who is actively working on protecting Black residents from low appraisals, to intervene by contacting the appraisal firm. Pratt had just been featured prominently on a local TV news station. He was a University of Chicago doctor, a son of the South Side, saving the area’s kids. This is the kind of person you want to deny a loan to? Robinson asked.

The appraisal came through the next day. Not as high as it should have been, Pratt thought, but enough for him to finally get his loan. Barely.

Pratt’s always on the go. There are the long ER shifts, the school visits talking to third-graders about staying safe on the streets, the free school sports physicals he arranges for kids who don’t have access to primary care, the working with contractors to rehab his new property, the driving his daughter to ballet and gymnastics and swimming, and, of course, the mentoring of kids in his program.

Even on a recent day when his surgical colleagues were the official teaching staff, Pratt was frustrated that something had gone wrong with the catering order. A medical student scrambled to order pizzas, and the kids loved them, but Pratt fretted that he couldn’t provide a healthier meal because so many of the kids live in food deserts.

He needs more help, and funding to run and expand his program. He’d like iPads and money for transportation for the kids. “My kids need tangibles,” Pratt said. “They don’t need a pat on the back.”

He has written eight major grant applications in the past few years, he said, and been turned down for them all. It bothers him that the killing of children in Chicago hasn’t yielded the surge of funding that followed the school shooting in Parkland, Fla., in 2018, which killed 17 students. It prompted Congress to set aside $1 billion to improve school safety, and Florida’s governor signed a bill to spend $400 million in his state. Parkland was a horrific tragedy, of course, but the day-to-day killings in Chicago claim the lives of dozens of schoolchildren each year.

The killings here are considered street shootings not school shootings, because urban schools often don’t have campuses like suburban schools. “That’s the kind of disparities we have in the inner city,” Pratt said. It’s not lost on him, or his kids, that attention and money seem to flow much more freely when white children are shot.

“It makes my job harder. When I talk to them they say, ‘Why should I care about innocent people being killed? Who cared when my brothers, cousins, and friends were killed … nobody,’” Pratt said. “It’s impossible to argue with that when there’s no history of the system prioritizing these youth.”

That sense of injustice isn’t helped by working in a wealthy institution every day, with constant reminders of the city’s haves and have nots. “There are so many resources here,” Pratt said. “But my community is getting nothing.” Individuals appreciate him, he says, but the system doesn’t. “Everyone likes to talk about equity but they don’t want to do anything. When there’s no funding, what they’re saying is that these students’ lives have no value.”

These are the difficult thoughts Pratt grapples with in quieter moments, but tries not to show. He doesn’t want to turn off the students he’s trying to inspire, or the med students and residents who came to the University of Chicago specifically to work on health disparities.

“My biggest fear is they see how hard I work, and I’m not even able to lift my family out of poverty,” Pratt said. He tells them they don’t have to be like him, and can still make a difference. Even if they take posh jobs in Boca Raton or Scarsdale, they can still apply the lessons they’ve learned here. “Every place has disparities,” he said.

Should he go to one of those locations? Or take a job in an outlying suburb? Life would be easier. He could probably afford a big house, pay off his loans, send his kids to good schools and all the expensive enrichment programs they deserve. But he also believes it’s important for successful Black professionals to stay in Black neighborhoods and serve as role models. And he knows he won’t be able to fight Chicago’s particular and devastating health disparities from afar. “My own narrative has built up a pressure to stay,” he said.

He doesn’t want to leave these South Side kids. It’s them, he says, who are saving him, keeping him going, and fighting, at a time when many physicians of all races are facing demoralization, burnout, and suicide. “This is what I have to do to sleep at night,” Pratt said.

And then there’s Rashad, who counseled him, just the week before he died, to remember to lift his community even as he rose. Now those words ring in his ears. “He told me ‘If you’re as smart as U of C says you are, you’ll be able to figure this out,’” Pratt said. “Ten years later, I haven’t.”

This is part of a series of articles exploring racism in health and medicine that is funded by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund.