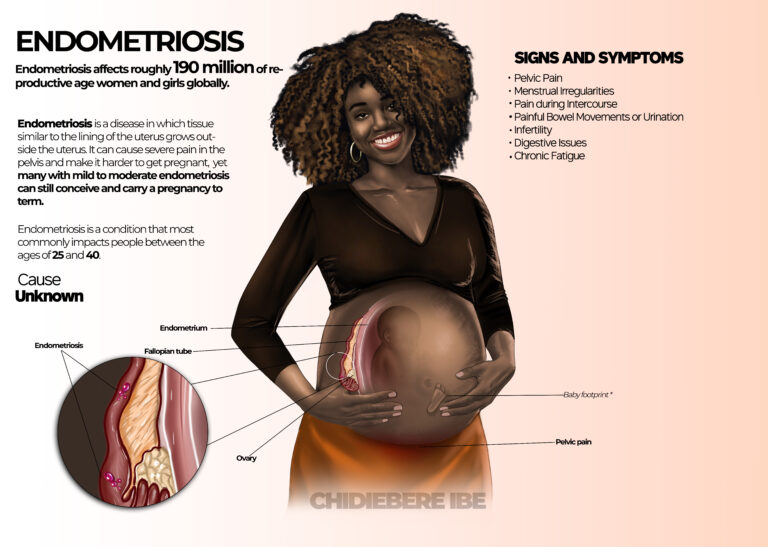

Medical illustration is both an art and a science. But it can have a huge cultural impact, too, as medical student and illustrator Chidiebere Ibe discovered when his illustration of a pregnant Black woman and her fetus went viral in 2021.

The image was groundbreaking precisely because it shouldn’t have been. People have a wide range of skin colors, and everyone develops medical conditions; it’s common sense that medical illustrations should feature a diverse range of bodies.

Yet a 2018 study found that only 4.5% of the images in medical textbooks feature darker skin tones. The lack of diversity in medical illustration can be dangerous. In dermatology, for instance, the scarcity of visual representations of skin conditions on darker complexions can lead to misdiagnosis. And for people of color, the dearth of images depicting conditions in non-white people could prompt them to ignore their symptoms and put off seeking medical attention.

When Ibe began teaching himself medical illustration in 2020, the then-24-year-old from Nigeria’s Ebonyi State was looking for a way to combine his artistic talent with the dream of becoming a doctor. He worked on a borrowed laptop that he plugged in at his church, where the power supply was steadier than at his home an hour away.

The success of his images ultimately helped Ibe crowdfund his medical education. Meanwhile, his work led to the creation of Illustrate Change, a library of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) medical illustrations created by the Association of Medical Illustrators with support from Johnson & Johnson and Deloitte. He is the chief illustrator of the Journal of Global Neurosurgery and has published a book on the importance of diverse visual representation in medicine, all while continuing his studies in medicine at Copperbelt University in Kitwe, Zambia.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When you started doing medical illustrations, was it with the intent of adding diversity?

No. When I started, I didn’t know anything about medical illustrations. It’s through the process of learning that I realized they didn’t represent people of color or Black people.

How did that lack of diversity influence your ability to learn medical illustrations?

I didn’t have any formal training on how to create medical illustrations. And to be able to teach yourself, you need good references to guide you through. I didn’t have them. So everything I drew was off my imagination. I would go and create these images and show my mentor. He offered guidance, but the lack of model resources was a big struggle.

For example, I would create a surgical procedure and maybe I wanted to show how the blood clots [look] on Black people. But I wouldn’t know how to represent it on a Black person because the illustrations I saw were all on white people.

Is that true even as a medical student? Does a mostly Black classroom of future African doctors learn medical symptoms on images of white people?

I would say that that is actually the case, yes. For instance, I took a course in pathology and realized that all the slides that were used in lecturing were skin diseases on white people. And I keep asking myself: Our patients, the majority of them are Black people, yet the resources to get them treated are white-centered; how does [the same disease] look like on Black people?

I realized that it was really a problem in Africa: in our textbooks, our lecture materials, our laboratories. For example, we have these mannequins in laboratories, and they are white. I really hope that in no distant time people will understand that this is a problem in health care in Africa. We can all work assiduously in addressing this issue.

The field of medical illustration is relatively small. How has your work been perceived within it?

I’m just about four years in as an illustrator, so my wealth of experience wouldn’t be comparable to someone who has been doing this for 50 years. For me, every day has really been a day to improve my illustrations, to make them more accurate, to put in all the tiny details from research.

I’ve had people who are very supportive, who suggest areas to focus on. I’ve also had people come into my inbox and say, “I think next time you could consider making the design better based on these notes, and maybe you consider taking away the smile [on the people you draw].” So of course I am open to learning, and that is the beauty of being an illustrator, because your work out there is not just for you.

With such a large need for diverse medical illustrations, how do you choose what to work on?

There are two ways I do that.

One, I pay attention to my followers and my audience. Sometimes people of color make comments on my posts, for instance someone who has PCOS or endometriosis, or someone who has a child with Down syndrome and doesn’t feel seen. I want to create illustrations that I know represent the community of people who are actually following me.

And the second way is about research, because what I do is ask, “What are the prevalent diseases in Africa? And how many of these diseases have been accurately represented?” So then I am going to create them.

And how do you go about creating them?

After the research, what I do is I look at the concept sketch, then I look for a suitable model. I sketch the outline, start coloring, ensure the anatomy is correct, and when that’s done I export the image, review the text, the labeling, and the anatomy in general.

I also think about the experience of patients who are going through the disease and see an image of it on Google. So for example, while it’s OK to create an image of a patient who is in pain, what about giving people hope through the illustration, by giving it a smile?

Did you ever expect your illustrations would go viral like they did?

I actually don’t know anyone who expects to be famous or go viral. I never expected it. And so for me, it was a shocker to see my work on LinkedIn have 5 million impressions, and about 3 million on Instagram, and the rest. And I think it’s just more reason to be humble and to work harder.

How has your work changed since your work has become more popular?

The older you get in a particular field the more patient you are, is what I noticed in the course of my learning. When I started I was so eager to get the work out that I would go too quickly, but in the course of learning I realized that patience is everything. So now I really take my time to do the research, my outlines, my painting and all of that. Also because I understand that my work is really out there, so I need to be sure it is very accurate.

Your work started a conversation about diversity in medical images. How do you think that discussion is changing the field?

In recent times there’s been an increase in resources out there. There’s a project [Illustrate Change] that I worked on in which we’ve built a library of diverse illustrations, and people are already collaborating and are already coming together to improve access. We partnered with Johnson & Johnson and Deloitte to create one of the biggest libraries of diverse illustrations out there, and so you see that collectively, many institutions or systems are now working together to improve access to these resources. And these things were not there before my images went viral.

And secondly, I’ve also seen more illustrators who are also focused on creating more diverse illustrations. I feel that is a great asset and I’m sure that in the next three years or so that if a research is conducted around the number of diverse images, that will be an increase.

You are also helping train a new class of medical illustrators out of Africa.

Some of the problems we have in Africa are due to lack of mentorship and empowerment. Medical illustration is actually a very small niche, and because it is small, that also affects the number of diverse images that we see out there. So my idea is, why not train more people who are willing to do the same thing so we can have more Black illustrations?

You are still pursuing training as a physician. How do you plan to combine your practice with your work as a medical illustrator?

I had to still pursue my dream of being a doctor, because that’s where I find my ultimate joy and my ultimate fulfillment. And also to improve my skill in illustrations, I needed to go to medical school. They’re not like two different things entirely. I am a doctor-to-be and I am also drawing things that are medically inclined. It is a beautiful experience that you can use your art to change lives, and use illustrations to change the perspective of people.

As a doctor, my life wouldn’t just be centered around the hospital; I would have some free time and I can make drawings of my daily cases, so I think there is really going to be a good balance there.

From a diagnostic perspective, what is the benefit of your body of images?

Medical students will one day become doctors and it matters what they are being trained with. It matters what kind of resources they get exposed to. Imagine here in Africa, if medical students aren’t exposed to — let’s say — skin conditions on Black people, how do you expect them to treat patients that come to them with that skin condition? An accurate representation ensures that the patients are treated accurately.

And I think ultimately it also helps patients to feel seen, because as much as they’re trying to improve health care outcomes, you also want to ensure that patients feel confident coming to the doctor.

Are your images being included in textbooks?

I don’t have access to organizations that publish medical textbooks globally, but I believe that people who have access to my illustrations do. So this is where collaboration comes in and people are like, “So can we review our textbook and what we’re doing? And can we ensure that more diverse images are being included?” I’m also aware of physicians who have printed my illustrations and hung them on their offices. That is really a great approach. That’s really fantastic. But I’m looking forward to seeing these images in textbooks.

And you have your own book.

I published my book, titled “Beyond Skin.” The idea behind the book is that if only physicians could look beyond the skin of patients, we would have an equitable health care system. So it’s a moral call to physicians to treat every patient fairly and rightly. And it is also the book that contains my journey as an illustrator.

What do you think is the ultimate goal of your illustration work?

It is to ensure that these images are in textbooks, and see that we do not use the skin as a basis for treatment, and this can be a result of accurate representation. And also, I long to see more people doing the same thing that I do, because it’s not about me, I want to see people be passionate about issues like this.

You were initially drawn to medical illustration as an artist. Do you still do other types of art?

I don’t do any other type of art anymore. This is obviously now my art.