Pat Furlong was sitting in her home office in Middletown, Ohio, last Thursday, refreshing a Food and Drug Administration web page ad nauseam, when the phone rang. She answered and burst into tears.

The FDA had just approved the first gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, her friend and the therapy’s architect, Jerry Mendell, told her. It was a culmination of advocacy work Furlong began 39 years prior, after her own sons were diagnosed with the fatal muscle-wasting disease.

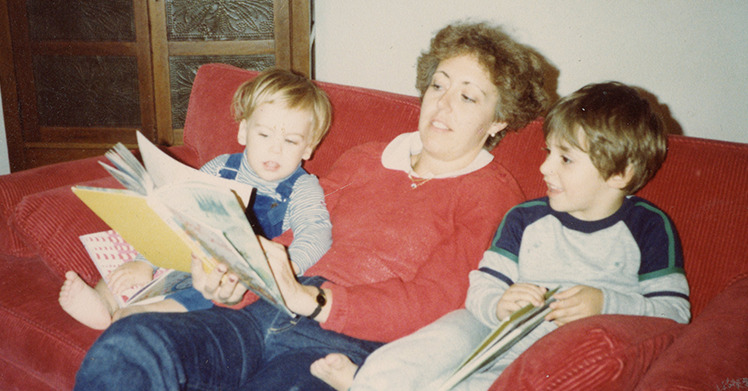

She thought back to them, Christopher and Patrick, and trips they had taken in 1992 to Memphis, where researchers were experimenting with implanting immature muscle cells into Duchenne patients. She was full of hope then. One of that year’s radio hits was Marc Cohn’s “Walking in Memphis,” and Furlong kept hearing the song’s central line in her head: You’ve got a prayer in Memphis.

Then the study failed. The cells did nothing. Within four years, Furlong had buried both sons, both still teenagers.

“And then yesterday, my thoughts went back there, too,” Furlong said in an interview the morning after the approval. “We have a prayer. You know, it’s not Memphis, but we do have a prayer.”

For Furlong and an entire generation of parents, the approval of Sarepta Therapeutics’ gene therapy, Elevidys, is an ecstatic moment, but one laced with pain. They mobilized for years to lay the groundwork, raising money for basic research, meeting with lawmakers, lobbying the FDA and educating biotech CEOs. Their sons participated in study after study, establishing foundational knowledge both Sarepta and regulators relied on.

Yet largely, those sons will not benefit. Some, like Furlong’s, have died. Others are now in their late teens and twenties and have already lost most of their muscle function.

Sarepta’s gene therapy might help preserve muscle, but it can’t rebuild what’s lost.

“It’s heartbreaking,” said Jennifer McNary, the mom of two men with Duchenne, both of whom rely on wheelchairs.

McNary, whose 2016 lobbying for an earlier, controversial Sarepta drug shifted the agency’s attitude toward rare diseases, calls this group the “legacy moms.” Mindy Cameron, the mom of a 21-year-old man living with Duchenne, calls these older boys and men the “lost heroes.”

“It’s a lot of joy, a lot of pride,” said Cameron, describing her emotions. “But I didn’t pay the ultimate price, my son did. And life is getting hard for him.”

They know there are limits to Elevydis. The $3.2 million drug, designed to deliver a miniaturized form of dystrophin, the gene broken in Duchenne, is not a cure and is only approved for (most) 4- and 5-year-olds, with a broader approval possibly coming for other ambulatory patients next year.

Yet they know it means that if a young boy is diagnosed today, his family will likely not receive the same punch-in-the-gut prognosis they all did: There’s no treatment, take them home, love them, come back when they need wheelchairs.

Their efforts over 30-plus years are a case study in the profound power and limits of modern disease advocacy. Beginning with Furlong, they created one of the most powerful disease movements since the AIDS crisis. That movement birthed a gene therapy for one of the most common rare diseases, something most regarded as science fiction. But science-fiction still came too slow, the pace of drug discovery always trailing the pace of Duchenne.

Nevertheless, many stayed involved through the decision, working with the younger, less experienced parents to help convince the agency they needed access to this treatment.

“This is perhaps the beauty and the pain and all of that of advocacy, right?” said Furlong. “You learn a diagnosis, you join a group that you didn’t want to join, that you didn’t know about, that you’d hope, in retrospect, that you never learned about. And then you become part of that community that wants the best not only for your children, but for someone else, because you’ve seen this.”

Each started in search of a cure for their son, believing they could beat the predictions textbooks laid out for the hundreds of children diagnosed every year.

When Furlong began, there were no treatments. There weren’t even clinical trials. She was a former nurse, though. She knew medicine. So she tracked down the scientist behind an old research paper and convinced him to start one. She offered funds from a loan she took out and assured her sons were included.

It failed. Almost everything did. After Memphis, she founded a nonprofit, Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy, to bring the field’s top minds together — and raise the kinds of funds required for better research. She wheedled, pleaded and occasionally lied, telling scientists a top luminary was coming to a conference to make sure they showed up.

And then, in a seven-month-span in 1995 and 1996, both Christopher and Patrick died. She was left in her Middletown home stewing in grief, angry at the world. She was broken, she said. A nurse whom medicine had failed.

The phone rang. It was Lee Sweeney, one of those scientists Furlong had lobbied. Stay, he said, you can do something important.

“It can be your get even strategy,” he told her.

In years that followed, PPMD secured hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for care centers and research, including some of the earliest work on gene therapy. They met with the FDA repeatedly, running surveys and writing guidance documents to explain what the community needed and the risks they were willing to take. When Jerry Mendell was ready to begin testing what would become Elevydis around 2016, Furlong raised the $2.4 million he needed for the trial.

Other moms traced similar arcs. Before Debra Miller started CureDuchenne, a venture philanthropy group, she was just trying to cure her son Hawken, now 26. But as a public charity, they couldn’t focus solely on Hawken and his particular mutation.

“The integrity issue takes over — that I’m not just here for my son, I’m here for all the families,” she said. She’d meet those families and “fall in love with those kids too.”

They grew used to disappointment, to being left behind by companies that shifted focus or concentrated on younger patients. CureDuchenne invested in or gave money to companies developing treatments for Hawken’s mutation. Then they’d pivot to different mutations for business or chemistry reasons and Miller would have no recourse.

Nostrums such as shock therapy and stem cells rose and fell, dividing the community in their wake.

Research trials generated hope but came with strict criteria. Companies wanted patients with the most muscle left to save. Mindy Cameron’s son, Christopher, enrolled in observational studies to help researchers understand the disease for future generations. But he was often just slightly too sick to be eligible for treatment studies.

In 2018, he was rejected from a trial testing a different gene therapy in older boys, and Cameron left Duchenne advocacy.

“It was like getting the whole diagnosis over again,” she said.

She did HIV work for a year and came back.

“I knew too much to do anything else,” she said.

When Sarepta started a trial on a mutation-specific drug in 2011, Jennifer’s McNary’s younger son, Max Leclaire, was eligible for treatment studies. Her older son, Austin Leclaire, wasn’t.

“This has been the theme of Austin’s life,” said McNary.

By 2020, McNary had stepped away from Duchenne work. Her efforts in 2015 to secure approval for that drug despite limited evidence — after she watched Max benefit in a trial, while Austin continued to decline — stoked tremendous backlash but altered the agency’s attitude toward patient demands. Afterwards, she consulted for companies and nonprofits hoping to do the same in other diseases. (She has also consulted for Sarepta.)

She returned after hearing chatter about a Sarepta gene therapy trial for older boys, the earliest in an ongoing effort to obtain wider approval. Per usual, Max was deemed eligible. Austin was not.

When it became clear FDA reviewers were skeptical of the company’s data, noting the only placebo-controlled trial failed (Sarepta attributes it to a study anomaly), she and Furlong worked with parents of younger kids to help the new parents communicate to the FDA how much they believed the treatment benefited their sons.

In May, those parents showed videos at a hearing of outside advisers: Boys with Duchenne walking up stairs with relative ease, riding bikes, playing sports. McNary thought of Austin, who has never once jumped.

“It’s a little bit of a kick in the gut,” she said. At the same time, “you’re so happy for the people who are you? Right? These are younger me. These are people who, you know, deserve all of the happiness.”

Their lobbying and those videos, combined with early data, persuaded FDA biologics chief Peter Marks to overrule his own reviewers and give the drug accelerated approval for a limited age group. Technically, it can be taken off the market if a confirmatory study delivers negative results later this year.

If that study is positive, however, and the agency both keeps the current approval and expands it to older ambulatory boys, advocates expect the community and their movement will change.

Cameron wonders if it’ll fracture. The pre-gene therapy population and the post. She wonders if the next generation will understand what they went through, what they did.

The face of the advocate community will likely change, too, becoming more and more the boys and men themselves.

“Is it still going to be called CureDuchenne? Is it still going to be called Parent Project?” asked Cameron.

That process has already begun, as a broadly improved standard of care has allowed many patients to live into adulthood. For them, knowing a next generation may face different odds has been heartening.

“It’s a whole new world,” said Buddy Cassidy, a 33-year-old man with Duchenne who served as the patient rep on the FDA advisory hearing, adding that he hopes it will help usher in therapies for other rare diseases as well.

At the same time, he has also been working on supporting patients as they transfer into adulthood, assuring they can go to college and receive the services and accommodations they need to live an independent life.

Austin Leclaire, who lives with Max in an apartment attached to McNary’s house, hopes to get the treatment eventually, if Sarepta can secure wider approval. But they know its benefits may be minimal. McNary thinks it might have helped stabilize Max, allowing him to lift groceries and cook.

At 21, Christopher Cameron, needs round-the-clock-care and lacks the muscle strength to blow his nose, but he’s a college student and an aspiring screenwriter and just this month, he and his family got back from an Alaska cruise, as part of his goal to see all 50 states. Mindy doesn’t know if he would get the therapy if it’s ever approved for the non-ambulatory, given the risks it might hold for sicker patients, but she’s glad it’s his decision now, not hers.

Some of the legacy moms are ready to hand off the baton to the next generation of parents and men. The next fight “will take new, less exhausted people,” McNary said.

Others aren’t slowing down. The Parent Project Muscular Dystrophy’s annual conference began Thursday. There is still so much to be done, Furlong said, ticking off a list.

How do they ensure everyone who is eligible gets access to the therapy, particularly boys who will soon turn 6 years old? How do they make it available to people who are currently ineligible because they have antibodies against the virus used to deliver the gene? How do they make it available around the world? How do they make even more effective drugs?

“It’s full speed, full speed, we can slow down when we’re assured that we have treatments for every single individual touched by a dystrophin-related disease,” she said. “Then we can slow down. But I don’t see that happening anytime soon.”