The Food and Drug Administration’s expert vaccine advisory panel on Thursday unanimously endorsed the idea of taking a strain of influenza viruses that no longer appears to circulate out of flu shots as quickly as possible, pressing the FDA and manufacturers to try to get the work done on an expedited timeline.

While a representative of vaccine manufacturers warned it may not be possible to remove the influenza B/Yamagata component from the flu vaccines that will be made for the Northern Hemisphere’s 2024-25 season, several members of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee suggested that should be a goal, at least for the U.S. market.

Arnold Monto, a veteran influenza expert from the University of Michigan, stressed that while there isn’t enough time left to recommend the B/Yamagata component be removed from vaccines soon to be made for the next Southern Hemisphere winter, it is possible manufacturers could clear the regulatory hurdles in time for the formulation of 2024-25 flu shots for the U.S. market. VRBPAC is scheduled to meet next March to vote on the 2024-25 winter flu vaccine composition.

Thursday’s meeting was called to vote on this question, as well as on what strains should go into the 2024 Southern Hemisphere shot. Two flu vaccine manufacturers — Sanofi and Seqirus — make Southern Hemisphere vaccines in the United States and export between 10 million and 20 million doses to 10 Latin American countries, explained David Greenberg, a Sanofi executive who represented the flu manufacturing sector at the meeting.

While a couple of members of the committee appeared to be leaning toward recommending the change immediately, Greenberg and Monto stressed that would threaten supplies of vaccine that Southern Hemisphere countries are already negotiating to purchase. In the end, the committee voted unanimously to recommend a formulation of the 2024 Southern Hemisphere vaccine that includes the B/Yamagata component.

“It would be quite disruptive to move ahead with removal right now in the Southern Hemisphere formulation,” said Monto. But he did not side with Greenberg’s suggestion that the industry may need two-full cycles — one for the Southern Hemisphere and one for the Northern Hemisphere — to effect the change.

“I feel uncomfortable at promising that B/Yamagata lineage would be included in the Northern Hemisphere formulation [for 2024-25],” Monto said. “I think we need to try to see if it’s possible to do it in the United States at least by the time we meet next March.”

Greenberg warned, though, that it is not clear all U.S. manufacturers could meet the timeline the committee appeared to be favoring, noting decisions are already being made about the Northern Hemisphere vaccine production for 2024-25. “At the end of the day, when it comes to filling and packaging the product to ship starting in July [2024] in the U.S., those decisions are made really in the next few months,” he said. “And so if we were to take that risk, I’m really worried that we would have a major shortfall in vaccine distribution next summer and fall.”

The VRBPAC vote followed a recommendation last week from the World Health Organization that the B/Yamagata component that is in some — though not all — flu shots made globally should be removed because that lineage of viruses no longer appears to be circulating. B/Yamagata was being outcompeted by the other flu B lineage, B/Victoria, even before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the committee was told. The social distancing, masking, and dramatic reduction of global travel that followed the start of the pandemic appeared to have sounded a death knell for B/Yamagata. No confirmed viruses of this lineage have been spotted since late March 2020, David Wentworth, the outgoing director of the WHO Collaborating Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza at the CDC, told the committee.

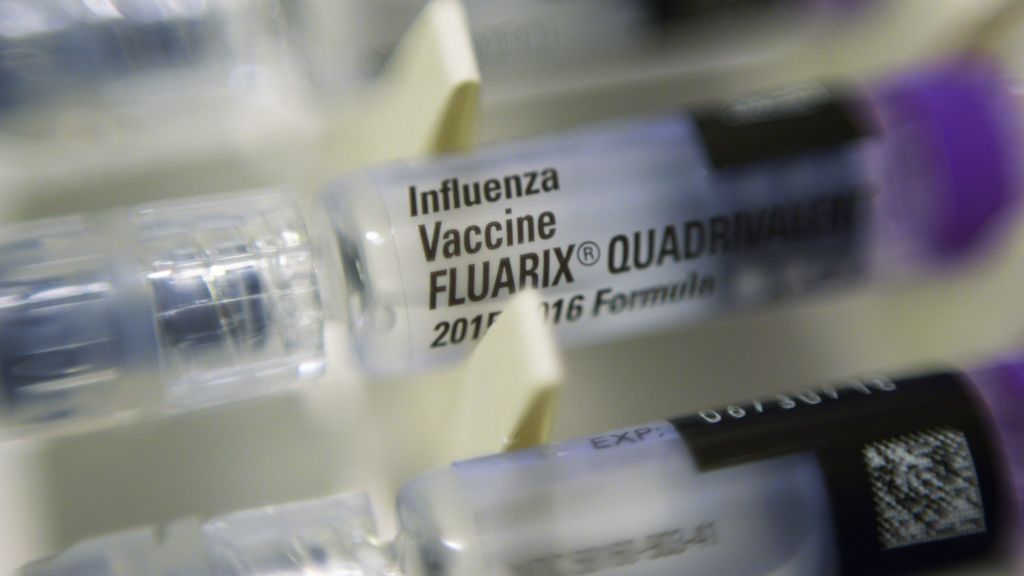

While the move to drop B/Yamagata from the flu shots is logical, Greenberg and the FDA’s Jerry Weir, director of the division of viral products at the agency’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, noted it took some years to move from previous trivalent (three-in-one) formulations of flu shots to quadrivalents (four-in-one shots) when it was decided in the late 2000s that adding a second lineage of flu B to the shots would increase the effectiveness of the jabs. After years of work, the first quadrivalent shots began to roll out in 2012.

Not all countries use quadrivalent vaccines; the four-in-one shots are mainly used in affluent countries. The U.S. flu shot supply at this point is exclusively quadrivalent vaccine.

A number of the previous trivalent licenses manufacturers of quadrivalent vaccines held still exist but have been discontinued, Weir told the committee. Procedures to remove them from the “discontinued products” list exist here. But procedures may be different in other countries, he said, warning it’s unlikely there could be a synchronized global switch to drop B/Yamagata from all flu vaccines.

The committee also discussed the idea of using the space in the vaccine that would be freed up by removing the B/Yamagata component to try to improve the performance of flu shots some other way, either by increasing the dose per component, or adding a second influenza A/H3N2 strain, to try to broaden protection against this particularly difficult family of flu viruses.

Weir said the FDA was keen to hear VRBPAC members’ thoughts on how this could be done, saying the burden of disease from influenza remains high and there is substantial room for improving the available vaccines. “And that, I think, presents us with an opportunity to ask ourselves whether this is a chance to make a vaccine that is somewhat better,” he said.

But Monto warned that while the influenza research community is intrigued by a number of ideas for improving flu shots, there is no consensus at the moment about the best path to do so and little research has been done to lay the groundwork for such a change. Greenberg noted that while individual flu shot makers are exploring ideas for improving the vaccines, they would need to conduct clinical trials before they could apply for licenses for reformulated quadrivalent vaccines. “I think as an industry we’re sincerely interested,” he said.