Prince Harry is returning to Netflix.

“Heart of Invictus,” produced by the Duke of Sussex’s Archewell label within the streamer, presents a view of Harry’s advocacy work. Director Orlando von Einsiedel and producer Joanna Natasegara — past Oscar winners for the 2016 documentary short “The White Helmets,” and nominees for the 2014 feature “Virunga” — knit together the stories of multiple participants in the Invictus Games, the athletic competition Harry founded for wounded veterans around the world. It’s a five-episode docuseries with uplift that can also be at times startlingly raw: Among the participants in the doc is a veteran in Ukraine, trying to move into civilian life; as Russia invades, she’s drawn back into the conflict.

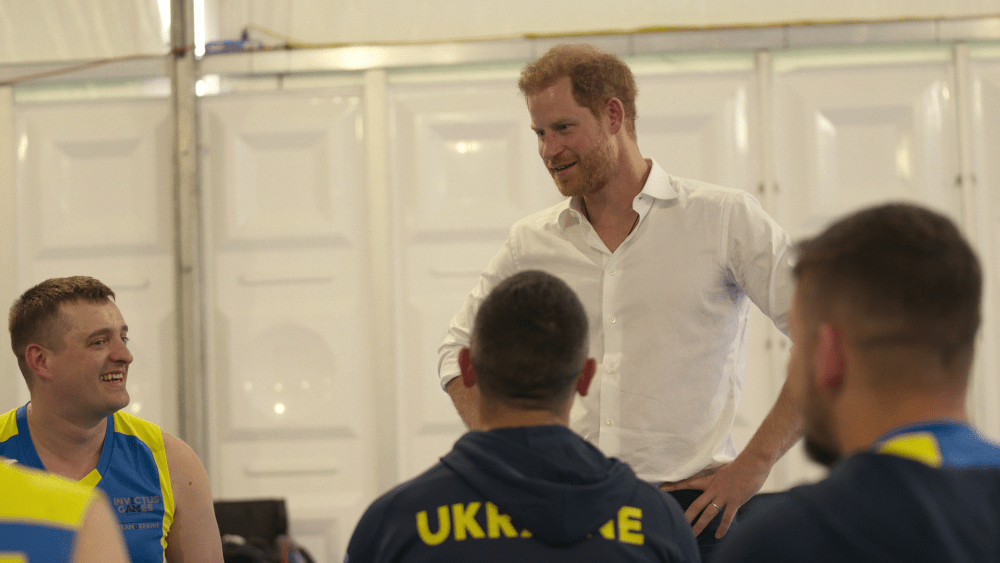

For Harry — who is one among von Einsiedel’s and Natasegara’s subjects, and gets equal time, but not star treatment — this is a chance to do advocacy work for his most passionately held cause (and, perhaps, to turn the page from projects like last fall’s docuseries “Harry & Meghan,” which was more closely focused on his personal life and family conflicts). But for the director and producer, the project was in line with the work they’ve done throughout their careers — and, von Einsiedel says, a chance to reframe their thinking about disability. Ahead of “Heart of Invictus” dropping on Netflix on Aug. 30, the filmmakers spoke with Variety.

What about this project appealed to you?

Orlando von Einsiedel: Jo and I, we’ve worked together for over a decade. And in that time, we’ve covered stories about the challenges of mental health; we’ve done a lot of work in countries experiencing conflict. And this was a project that brought together a lot of our past work. It was an opportunity to tell a story in the aftermath of war, about people on a journey of recovery.

There’s a slight Trojan-horse effect at work here: I suspect many people will watch because of Prince Harry’s name and reputation, but the preponderance of this documentary focuses on far less famous figures. It must have been an interesting challenge to balance both sides of the story.

Joanna Natasegara: For us, Prince Harry’s commitment to the Invictus community was very clear, and very obvious. He is in and of that community — and so you see that within the show. I don’t mind how people are attracted to the show, but I really hope they take away what we took away, which was a universal message of hope and resilience.

I was really struck by how nimbly the production responded to the war in Ukraine. Taira, one of the people you follow, wears a camera to record her volunteer work at a hospital near the front lines in Mariupol. That seemed, among other things, like a huge production challenge.

von Einsiedel: When we started filing, it was a long time before there were even rumblings of the conflict — we started following Taira on this journey to become a civilian again, from her injury after almost a decade of being a volunteer paramedic. All of us watched with horror at the Russian invasion. That was not the kind of series we were trying to make. But Taira was documenting her work in a way that she might have done anyway, and sharing that material with us.

In general, I found the people whose stories you told really open and candid — which surprised me, because I might have expected a sort of stoicism. What went into convincing your subjects to share their stories?

Natasegara: We had a very mindful casting process — for want of a better phrase, as it really isn’t about casting. It was about meeting people who are open to the process of documentation, and we spent quite a long time talking to them about what that feels like. We all know as documentary makers that’s not an easy thing that you’re asking people to be in with you. So we wanted to make sure that people were really sure that they wanted to do that.

People wanted to do that for all sorts of reasons. Very often, a common theme was the same as military service: Service to others, to share stories that might help someone else. We worked very closely with a production psychologist to ensure that people were filming in a way that was comfortable and appropriate for them.

von Einsiedel: At its most simple, the way that Jo and I have made films over the years is we tried to do them really slowly. That’s building these relationships of trust, doing it step-by-step with all of the contributors, and making sure everybody’s comfortable along the way.

What did that process look like with Harry in particular?

Natasegara: We treated the Duke as we would any other contributor — the same process, the same duty of care, the same respect. And the same questions. It was really important to see him in the same way as the others, and I think he comes across in the same way, as an equal, to the others in the show. You have to be respectful and work slowly to gain people’s trust, and when they feel there’s a shared agenda, that trust is more easily won.

Much has been written and reported about Harry as a producer. I wonder if you could speak to your experience working with him as a creative collaborator on this project.

Natasegara: Unsurprisingly, he’s very engaged with this project. He cares deeply about the community, cares deeply about how those people are presented. He cares deeply about mental health, and about sport as a tool for recovery. So he was a great partner. We really enjoyed making this series, top to bottom.

Has this project reframed how you’ll think about your work going forward?

von Einsiedel: I’m going to give a really simple example. We were filming with Prince Harry in California, with JJ Chalmers and David Wiseman, who were two of the early Invictus competitors. JJ, who was injured in a bomb attack in Afghanistan, said, “Look, my injury has changed the way I look at the world. It’s made me a more understanding and empathetic person.” I probably had a very naive, ableist outlook on what an injury might do to you, so it really blew my mind hearing him say that. A lot of people working on this show learned an enormous amount abou their own prejudices and blind spots.

I wonder if you could speak to the challenge of integrating a global celebrity into a story about so many other people who are less well-known. Harry has spoken about his struggle with PTSD, and that’s the subject of the film — but he also has a pre-existing public image that people are familiar with.

Natasegara: I think what we’ve learned is that everybody has a story. We sort of knew that, but this series, and this community, brings that home more than most. Looking at the fact that people have different needs, they have diverse bodies and minds, but what are those needs? Everybody is on their own journey, and all you can look at is their journey, and supporting them on that. It doesn’t matter where somebody comes from. That has been completely transformative for us: It makes every playing field level.

This interview has been edited and condensed.