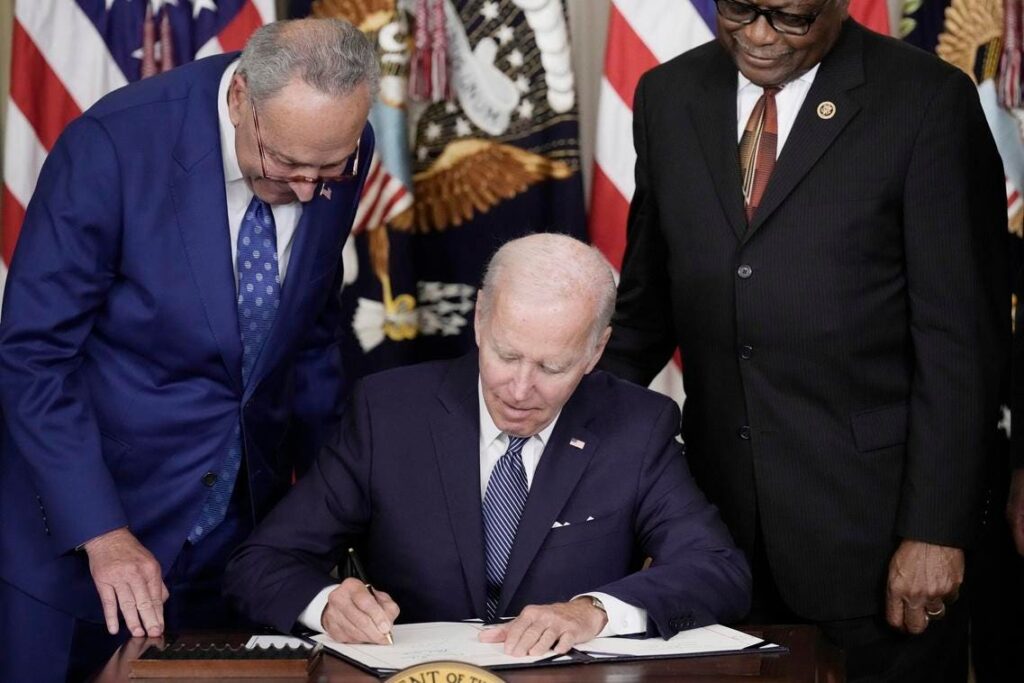

WASHINGTON, DC – AUGUST 16, 2022: U.S. President Joe Biden (C) signs The Inflation Reduction Act … [+]

The Inflation Reduction Act isn’t explicitly focused on curbing market entry impediments, but through actions taken by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services–specifically, its selection of certain biologics for the initial round of price negotiation, such as Enbrel and Stelara–it appears to be indirectly entering the fray.

Biologics account for more than 40% of current prescription drug expenditures, while only representing 2% of all prescriptions. So on a per prescription basis, biosimilars–which have active ingredients similar to those of a previously licensed reference biologic–can yield substantial cost savings.

Manufacturers of the reference or originator biologics often build so-called patent thickets around their products to ward off competition from biosimilars. Due to biologics’ complex structure and manufacturing processes, there are more patentable opportunities than small molecules drugs.

Extending monopolies has proven to be quite lucrative. Four blockbuster drugs—Humira, Avastin, Rituxan and Lantus—generated 56% of their overall revenue after expiration of their initial patents.

Among the drugs selected for Medicare price negotiation, the biologics Enbrel and Stelara are considered long monopoly products. When the Enbrel-referenced biosimilar Erelzi launches in 2029 it will have had to wait 13 years following its approval before entering the market. And a patient advocacy group suggested that the manufacturer of Stelara “makes an additional $18 million” in daily revenue by extending the product’s market exclusivity.

With the selection of Enbrel and Stelara CMS appears to be sending a message to manufacturers with long monopolies to accelerate the path towards competition or else face potential price consequences.

All told, patent litigation has postponed many companies’ ability to launch biosimilars. In fact, there are at least 15 biosimilars that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration but have yet to enter the market.

A frequently heard retort from originator biopharma companies is that they are simply defending their intellectual property to the full extent of the law, which technically speaking is true.

Nonetheless, originator drug manufacturers have been heavily criticized by Congressional lawmakers. Legislators recently advanced a proposal through the Senate Judiciary Committee which would restrict several of the legal maneuvers available to drug makers. Specifically, the bill would limit how many patents originator companies can claim that are applied for more than four years after the initial approval of their branded product or that protect manufacturing processes that aren’t actually used.

Notably, the same committee approved similar legislation last year, but it did not get a vote in either house of Congress. It’s unclear if the most recent proposed piece of legislation has a better chance.

Patent thickets are among the reasons why biosimilars have so far had a much smaller impact in the U.S. than in Europe, where there is less expansive use of patent laws. European authorities have also approved more than twice as many biosimilars–93 in total–as the U.S. And, across most therapeutic classes in which biosimilars have been approved there has been more rapid and extensive biosimilar uptake.

European reimbursement authorities’ purchasing practices invariably favor lower priced therapeutic alternatives. In deploying health technology assessment, for instance, entities such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK, advise healthcare providers to use the lowest cost treatments when given the choice between equally effective alternatives. This is not always the case in the U.S., as payers sometimes prefer higher-priced treatments. This is because the rebates accruing to payers and the entities who contract with them are higher.

Consider, for example, the mega blockbuster therapeutic, Humira. Its primary patents expired in 2016, but because of secondary legal protections AbbVie was able to forestall competition in the U.S. until this year when the first biosimilar competitor, Amjevita, was launched. Thus far, however, there has been minimal uptake of Humira-referenced biosimilars in the U.S.

Meanwhile, throughout Europe reimbursement authorities strongly favor Humira-referenced biosimilars, which have already been on the market for more than five years and have garnered 75% or higher market shares in many jurisdictions.

In short, originator biologic manufacturers have far less leverage across Europe than they do in the U.S.

Constructing patent thickets may be legal, but it isn’t consistent with a robustly competitive marketplace. Perhaps accelerating the timeline for biosimilar (and generic) market entry is what the IRA had in mind when it chose several long monopoly products as part of the first batch of drugs to undergo Medicare price negotiations.