For all his athletic prowess, all the heft he brought to his social activism, Jim Brown’s power sprang from his unyielding resistance to the narrow definitions imposed by American society on its Black citizens and, in his case, Black male athletes.

The resounding power of no. That is what Jim Brown embodied.

Brown, who died Thursday at 87, lived a life that became an ode to self-determination in the face of stinging racism. He refused to be limited by what others said he could become. He demanded to be seen in his fullness, as a complete human being, with all sides of himself recognized. In keeping with that wish, paying homage to his achievements cannot be adequately done without noting his deep faults.

But we start here with Brown’s life in sports, for his career as an athlete was truly unique.

In college at Syracuse, Brown dominated on the football field as few ever have. But that is not all. He lettered in track and basketball. And in lacrosse, he became an all-American and was considered one of the greatest to ever play the sport.

As a running back for the Cleveland Browns, he racked up mind-bending statistics. In his nine seasons, Brown never missed a game. He won three league M.V.P. awards and an N.F.L. title. His average of 104.3 rushing yards a game is still a record.

Statistics tell only part of his story. His style of play — aggressive, hard-nosed and canny — made a singular demand on defenses. He was not going to do the job for them. Instead of stepping out of bounds when veering near the sidelines, he turned upfield and dared defenders to bring him down, forcing the opposition to deal with every bit of his strength, speed and 230-pound body.

He made similar demands on America, refusing to be boxed in, resisting society’s impulse to flatten his humanity. Such boldness ended his football career.

In 1966, as he pursued a budding career as a Hollywood actor during the off-season, he was filming “The Dirty Dozen” in England when poor weather slowed production.

This was an era in which team owners in professional sports regularly sought to exert dominance over players. That such aggression so often fell on Black players with extra force was part of the reason that most did not push for their rights. But Brown was not like most players. When Art Modell, Cleveland’s owner, found out that the film delays would cause Brown to be late to training camp, he threatened to dole out fines to his team’s star running back for every day missed.

Brown did not take well to that threat. He considered it an insult so severe that he decided he would not allow Modell to benefit any longer from his services. He was still well in the prime of his career at age 30, coming off an M.V.P. season in which he had rushed for 1,544 yards and 17 touchdowns. But he refused to be treated like just another cog in the machinery of the N.F.L., which was rising in the mid-1960s into a new era of popularity. He called a news conference and retired. He was not going to be pushed around or disrespected.

Brown’s insistence on resisting power extended far beyond making demands merely for himself. He was at the forefront in the wave of athlete activism that helped define sports in the 1960s.

There Brown was, in the winter of 1964, on the evening Cassius Clay defeated Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title, meeting after the fight with Malcolm X, the singer Sam Cooke and Clay, who later became known as Muhammad Ali. The four men spent the night discussing the ways they could best battle racism.

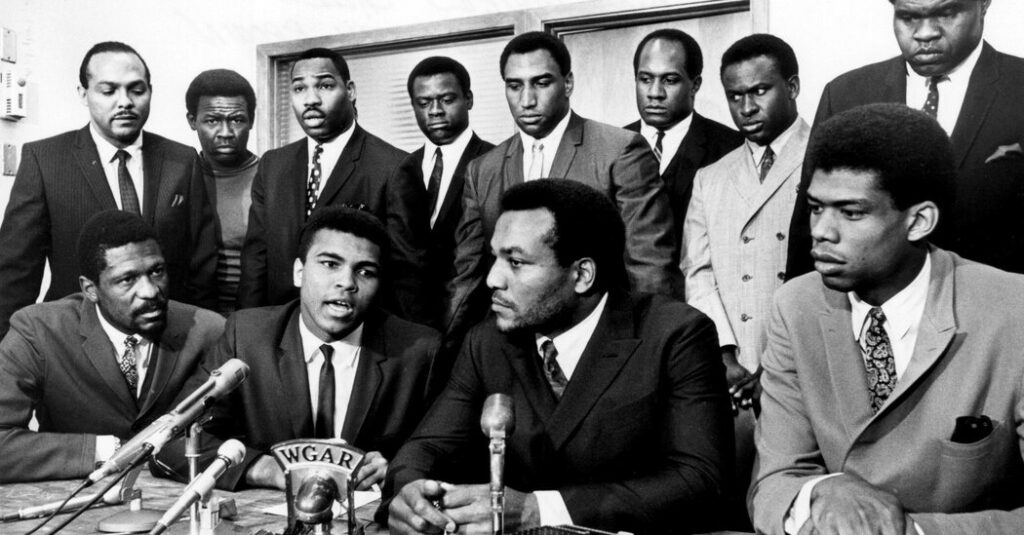

There he was, in the summer of 1967, summoning Ali, Bill Russell, Lew Alcindor (the future Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), and other prominent Black athletes to Cleveland. Ali had lost his heavyweight title and faced imprisonment for protesting the Vietnam War by refusing to be drafted into the military. Brown and the others listened to Ali explain his intentions, and then bathed the boxing champion in support.

Brown became a well-known spokesman for Black uplift. He founded an organization promoting Black economic mobility, which he saw as a more powerful way to make change than street protests. He started the Amer-I-Can Foundation, which helps people in gangs and in prisons straighten out their lives.

What a life. And what a statement made with that life. But there are no perfect heroes. For all the times he refused to bend to power and all of his athletic conquest, Brown was also a flawed man. From the 1960s to the 1990s, he was arrested several times for violent behavior, with some of those cases involving allegations that he battered women.

He was never convicted of a major crime, but the accusations pointed to problems that shadowed him. “I can definitely get angry, and I have taken that anger out inappropriately in the past,” he told Sports Illustrated in 2002, before adding to the admission in a way that only underscored his faults. “But I have done so with both men and women.”

Amid the hosannas, the troubling aspects of his life should not be glossed over. Through his resistance, he demanded to be seen as fully human, all parts of himself acknowledged, and that is how we must view him in death.