When European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen visited Beijing in April, Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed to her that “sound development of China-EU relations would not be possible if the principles of independence, mutual respect and mutually beneficial cooperation are not upheld.” He went on, saying that China and the EU need to “strengthen communication [and] foster a right perception of each other” while avoiding “misunderstandings” and “miscalculations.”

Judging from the EU’s relationship with Beijing in the past few years, Xi’s rhetoric may seem plausible. The COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with outlandish remarks by “wolf warrior” diplomats and the EU designating China as a “systemic rival,” have proven that European policymakers are increasingly wary of China’s economic and political influence. Any parties wishing to restore and maintain functional diplomatic and trade relationships cannot do so without trust and respect – as Xi has said. Yet, taking his words at face value is not only naïve but also neglects the known and hidden risks of trading with the world’s second-largest economy and largest authoritarian country.

Trading with China has proven to carry its fair share of risks, as Beijing is known to leverage its enormous market and trading powers for political gains. Despite growing China skepticism, China remains a key trading partner with the EU, and European trade with China has become even more prevalent. In 2012, the EU exported 132.2 billion euros worth of goods to China, which rose to 230.3 billion euros in 2022.

However, the relationship has become significantly unbalanced, with the trade deficit rising from 117.9 billion euros to 395.7 billion euros in the same period. Much of this imbalance is facilitated by China’s political agenda and state capitalism. Such unbalance prompted von der Leyen to comment in her speech that one “can expect to see a clear path and push to make China less dependent on the world and the world more dependent on China.”

This unfavorable footing is motivating policymakers to reexamine Europe’s trade relationship with China. The most used metric for this task is arguably bilateral trade, which is the easiest way to understand which countries China has the most influence upon. The trade volume between China and Germany in 2020 was 212 billion euros, followed by the Netherlands with a trade volume of 93 billion euros and France with 62 billion euros, according to data from the European Union’s statistics agency Eurostat.

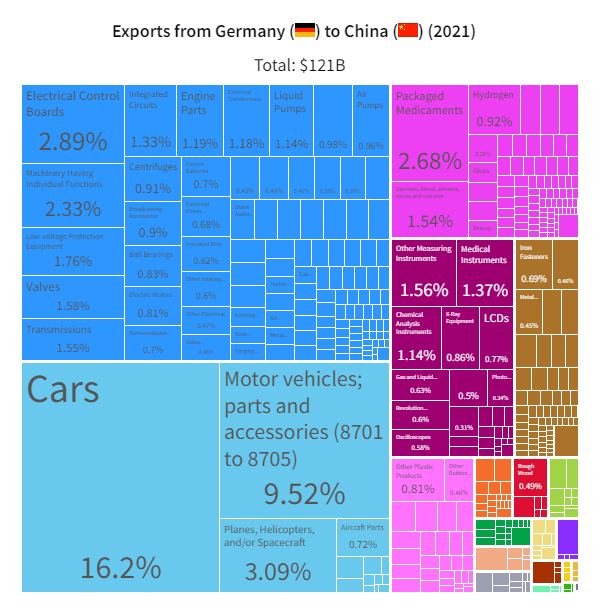

This data is certainly helpful to understand vulnerabilities. For example, considering that automobiles comprise over 16 percent of Germany’s exports to China – and with related sectors included, the total goes up to 25.7 percent, with a value of $31 billion in 2021 – it is not hard to understand why German automobile businesses, and some politicians are reluctant to upset their largest trading partner.

The breakdown of Germany’s exports to China in 2021. Data and visual from the Observatory of Economic Complexity.

While bilateral trade exposure is a time-honored way of examining business relationships and risks, it does not show the full picture. Some countries are heavily involved in the intermediary stages of the global supply chain vertical; their exports may likely be passed on through the supply chain to other countries. In this case, these countries are economically exposed not only to their exports’ immediate destination countries, but also to the final destination of the exported goods. This phenomenon creates a “final demand exposure” that, if overlooked, can grossly blur where a country’s economic risk is coming from and by how much.

Applying this model to the EU, we can see that some member states have significantly underestimated their exposure to China’s influence. For example, while Lithuania has a very low proportion of exports to China, the picture changes drastically once supply chain activity is considered: China takes up 3.9 percent of Lithuania’s exports instead of a mere 1.1 percent if one only considers direct trade figures. A similar trend can be observed in many EU member states, especially those from Central and Eastern Europe, where the discrepancy between bilateral export data and final demand exposure to China can be as high as 250 percent.

This underestimation of exposure led to Lithuania’s woes in 2021, when it faced economic pressure from Beijing after allowing Taiwan to open a representative office in Vilnius.

Tensions between Lithuania and China appeared as early as 2016 as Beijing’s relations with Europe deteriorated. After the 2020 elections, Lithuania’s foreign policy gradually shifted toward Taiwan to better align democratic values. Things came to a head with Lithuania approving the opening of a “Taiwan Representative Office” in Vilnius.

Beijing regarded the name “Taiwan” as violating its One China principle. In retaliation, Beijing blocked Lithuania’s exports to China. It also warned that firms that sourced products from Lithuania could be barred from the China market. As key EU economies like Germany and France have relied on Lithuania for their export supply chains, Beijing found the ideal strike spot.

German business entities like Continental AG, which sourced automobile parts from Lithuania for its China-bound vehicle exports, found themselves caught off guard, with the great risk of losing the China market. The fear was strong enough to pressure the German-Baltic Chamber of Commerce to urge Vilnius to craft a “constructive solution” – an euphemism for complying with Beijing’s policy wishes.

In the end, the EU stood up for Lithuania with 41 members of the European Parliament urging a united response against Beijing’s coercion. Even so, this episode unveiled the risks of over relying on an authoritarian market that is eager to change its terms for political needs.

That said, given the globalized nature of today’s trade economics, a full and abrupt decoupling with questionable partners will disrupt each country’s economy to the point that it would certainly cause more harm than good. A nuanced and sustainable approach, instead, is to manage and mitigate the risk. As NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg cautioned: “We should continue to trade and engage economically with China…but our economies and our economic interests cannot outweigh our security interests.” This more nuanced approach has been dubbed “derisking.”

While the amount of derisking Europe needs to do to meaningfully reduce its reliance on China may differ according to the individual member state’s circumstances, there are several policy directions that countries can identify and use.

First, to manage and mitigate risks posed by economic relations with authoritarian regimes, EU member states should comprehensively analyze economic relations with a global scope. These analyses should include mapping exposure, quantifying and tracking indirect relationships, identifying impacted industries and firms, and considering both benefits and risks of outward and inward investment in China. This kind of analysis must have a global scope, as relocation of supply chains, investments or trade activities away from China may create new dependencies elsewhere.

Second, EU government agencies should regularly communicate with the largest firms engaged in foreign trade to strengthen public-private dialogue on supply chain risks. The key is establishing dialogues on the importance of supply chain resilience, educating firms about the latest developments and best practices, and identifying critical industries and materials for mandatory disclosure of supply chain issues and exposures.

Third, governments must promote a corporate culture of transparency, corporate social responsibility, and accountability among companies engaged in business relations with authoritarian states. Companies should also promote such a culture among their employees to encourage them to blow the whistle when they come across illegitimate or illegal behavior connected to authoritarian coercion.

One caveat remains that amid the United States’ intensifying rivalry with China, European countries may find themselves trapped in the middle. While trying to balance security and business interests in China, politicians would understandably not want to be seen in lockstep with either Washington or Beijing (see, for example, French President Emmanuel Macron’s controversial comment on “strategic autonomy”). In these cases, the derisking framework will come in handy, letting EU member states react to risks as they arise while leaving legitimate trade frameworks unaffected. There is one condition for this model to be successful – as member states implement their derisking strategies, they need to signal a clear and unified commitment to deter malicious trade behavior.

An ideal trade relationship with China balances risks while future-proofing trades and political interactions. With new trends such as the green economy becoming more prominent and the EU naming copper and nickel as strategic materials, now is the time to ensure the EU’s overall supply chain and trade mappings will not be turned against the bloc, and instead, will become sustainable and mutually beneficial for the long run.