Today marks the beginning of Bola Tinubu’s presidency in Nigeria. The incoming administration faces a daunting set of challenges, including persistent insecurity and an unstable economy.

One of the issues that continues to dog Nigerian politicians is medical tourism, or travel abroad to seek medical care. Nigerian elites spend huge sums on overseas healthcare – amounting to over US$ 7 billion between 2016 and 2022, according to the newspaper PUNCH.

It’s big business for the overseas medical facilities, some of which have dedicated international marketing and welcome units, including arranging transport and language services. Others work with medical tourism agencies to facilitate referrals.

The trade can also be lucrative for medical tourism facilitators in Nigeria. These may be doctors or other agents who refer well-heeled clients to healthcare providers overseas, receiving a commission. The ethics can be murky.

Olusesan Makinde, the managing director of Viable Knowledge Masters, a health and development consultancy, believes that “there’s high potential for abuse” in the system. He says that medical practitioners have an ethical obligation not to advertise medical tourism services. This can lead to “physician-induced demand” for unneeded services, as well as a mismatch between what is being advertised in glossy international campaigns and the actual quality of services.

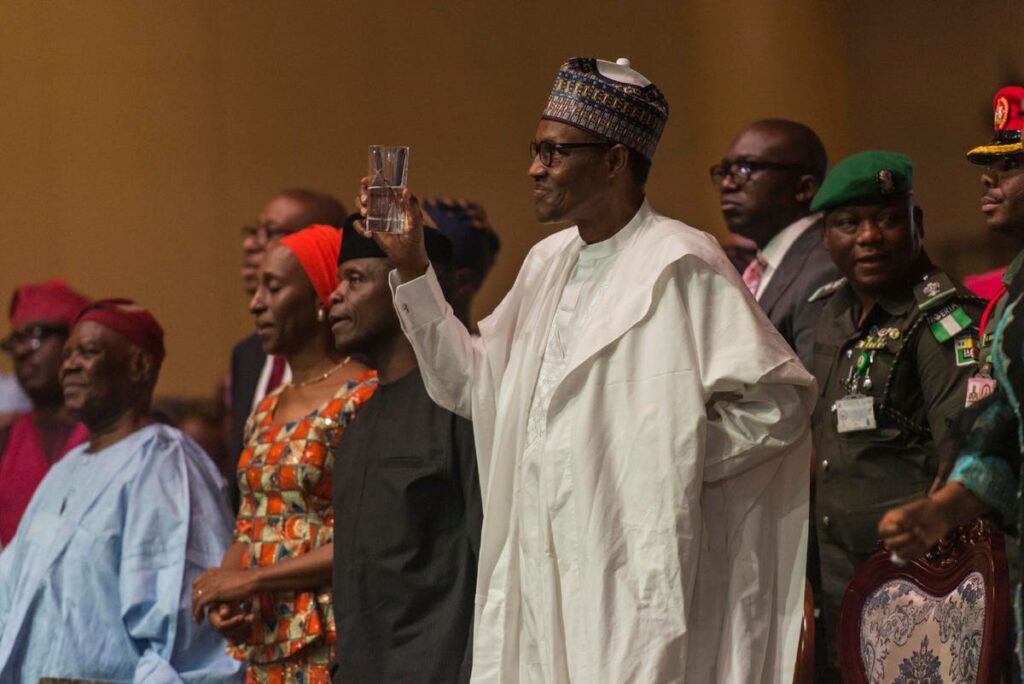

Outgoing Nigerian president Muhammadu Buhari toasts incoming president Bola Tinubu in 2018. (Photo … [+]

Common destinations for Nigerian medical tourists include India and the UK. One estimate is that for surgeries, 30,000 Nigerians went abroad in 2019. These include orthopedic, cardiac, and other surgeries.

Some tragic surgery cases involving Nigerian medical tourists have become international news. In 2005, Nigeria’s former first lady, Stella Obasanjo, died suddenly in Spain during a liposuction procedure in which a tube was mistakenly inserted into her abdominal cavity, puncturing her colon. Four years later, the plastic surgeon was convicted of negligent homicide.

Kidney transplant surgeries are also performed on Nigerians abroad. In a notorious 2023 case, Nigerian senator Ike Ekweremadu, his wife Beatrice, and the doctor Obinna Obeta were declared guilty of conspiracy in trafficking a 21-year-old street vendor from Lagos to the UK in order to harvest his kidney and transplant it into the couple’s sick daughter. The victim was able to escape after overhearing of the plot’s details.

Doctor Obeta, who housed the victim, arranged the transplant through a medical tourism company charging £10,000. He ran a private hospital in Nigeria and had previously received a kidney transplant in London himself. Obeta said that he had been afraid to have the transplant for the Ekweremadus’ daughter carried out in Nigeria or India, due to the high death rate of the procedure.

These are extreme cases, but they point to a link between Nigerian politicians’ families and medical tourism. It’s difficult to blame well-resourced individuals for making the choice for better care. As Chidiogo Akunyili-Parr writes in I Am Because We Are: An African Mother’s Fight for the Soul of a Nation, “To carry out an operation to remove the tumour in Nigeria, as opposed to a country with better medical facilities, was undesirable for anyone with any option.” The author’s mother, the revered drug regulator Dora Akunyili, received treatment for cancer in the US and India.

In one 2014 incident, family members even woke up the Indian ambassador to Nigeria to quickly obtain a visa for an emergency trip. The trip proved disappointing. The Bangalore hospital was dirty and dodgy; it had promised cutting-edge treatment but the family realized that this was just chemotherapy.

Of course, the vast majority of Nigerians don’t have the resources to travel overseas or pay private healthcare costs in another country (let alone a contact at the Indian embassy or access to a private jet). “The income gap between the ordinary people and the political class is so wide,” Makinde comments. Also wide is the gap in life expectancy between Nigeria and other lower-middle income countries. According to the World Bank, Nigeria has a life expectancy of just 53, compared to 60 for Nigeria’s neigbors Cameroon and Benin.

Since Akunyili’s tenure, medical tourism has remained rife among Nigerian politicians. Some detractors referred to the outgoing president, Muhammadu Buhari, as the medical tourist in chief, due to his unprecedentedly frequent journeys abroad to receive medical and dental care. These trips extended to the end of his presidency, notably toothache therapy in the UK on the heels of a coronation visit. One estimate is that his trips have added up to a staggering 5.4 billion naira (US$ 9.95 million). However, it’s impossible to know the exact expenses of Nigerian politicians’ medical tourism, as these are not disclosed publicly.

Though the exact amounts are unknown, the estimates are enough to make clear that significant government resources are enriching private healthcare providers abroad. Makinde believes that this represents wastage of public funds, in valuable foreign currency, that would be better channelled into supporting Nigeria’s ailing healthcare system.

“A lot of health facilities in Nigeria, they don’t even have power,” Makinde points out. Amidst Nigeria’s persistently unstable energy supply, there have been reports of medical staff using flashlights or even candlelight to work.

Politicians who don’t have to be exposed to the weaknesses of local health facilities don’t have as much pressure to reform them. A further issue is that people treated abroad can introduce novel microorganisms into their home countries, compromising other people’s health. And, of course, follow-up care for medical tourists is challenging once they’re thousands of miles away from the places where they received treatment.

Surgery in a hospital in Maiduguri, in northeast Nigeria. (Photo by Audu Marte)

Some politicians have proposed piecemeal solutions. A common one is investments in high-end medical technology and facilities. The outgoing First Lady, Aisha Buhari, has commented that her husband’s lengthy stay in a London hospital in 2017 sparked the idea for the recently inaugurated presidential wing of the State House Medical Centre. She didn’t want her family going to a hospital serving the public.

Nigeria is also developing its first cancer hospital, and other advanced facilities are being planned using Nigeria’s oil wealth. These new facilities would disproportionately benefit the wealthy, who of course are the ones who can seek out medical tourism. In general, lower-level health spending benefits many more people and is more cost-effective, but basic care isn’t the type that excites breathless ribbon-cutting.

In any case, without enough specialized staff, this infrastructure, no matter how impressive, won’t be used. And unfortunately medical staff have been departing Nigeria in huge numbers, given low salaries and poor working conditions. This has led to the sad irony of Nigerian elites leaving the country to receive healthcare abroad, where they are sometimes attended by Nigerian migrant staff. The main problem is not the shortage of Nigerian medical talent.

In fact, one proposal to curb the departures of Nigerian medical trainees has ignited furious controversy. A bill sponsored by a legislator from Lagos would require medical and dental health workers, trained at public institutions, to practice in Nigeria for five years before obtaining the full licenses that would allow them to move abroad.

The proposed bill has led to an angry response, including an argument to ban politicians traveling abroad for medical purposes for five years, rather than penalizing medical staff. The president of the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors, Emeka Orji, commented of the dispute, “The thing aiding medical tourism is because politicians and those well-to-do do not believe in our health system. So, they choose to go outside of the country and that is why they have not been able to upgrade the hospitals to international standards. If we are all using the same health facilities, the situation would have been better.”

“I feel like it’s not fair,” agrees Michael Sotomi, a third-year medical student at the University of Lagos. “Five years is a long time.” If the law had existed when he had been considering where to study medicine, he might have gone to a private university within Nigeria or studied abroad in Ghana.

“The main reason why people are leaving is the negative condition of the economy,” Sotomi says. If that improved, he might choose to stay and practice surgery in Nigeria rather than dreaming of moving to Scotland.

Makinde, who himself was a medical student about 25 years ago, remembers a very different situation. Then, medical tourists would come from other West African countries to receive treatment in Nigeria. Saudi royals even received care in Nigeria in the 1970s.

This could happen again, Makinde believes. Turning Nigeria into a destination rather than a source for medical tourists would require improvements to the economy and electrification, as well as larger health facilities and more specialty care. But one of the biggest changes needed would be a model of better accountability to the public, according to Makinde.

This is exactly what people are asking for from Tinubu as he takes office. Some have called on him to end medical tourism. Tinubu’s own recent travels to receive follow-up medical care in France suggest that it will be hard to set an example for other Nigerian politicians, but such example-setting would be one useful component of an ambitious overall package to improve health in Nigeria.