A few hours before some of the world’s fastest runners would run a few hundred meters very quickly, they were invited to walk some 30 meters very slowly.

The walk-in, organized by Noah Lyles, came with a dress code.

“If you’re warming up in it, it’s wrong,” Lyles, an Olympic and world championship medalist, said ahead of the N.Y.C. Grand Prix, a U.S.A. Track & Field meet held on Saturday at Icahn Stadium on Randall’s Island.

Lyles, one of the biggest names in the sport, is on a mission to add track to the list of sports that have transformed an unremarkable walk to the locker room into a red carpet photo op.

The idea came to him as he was scrolling through Instagram last year after GQ magazine posted some of the best outfits worn by professional athletes as they walked into stadiums around the world.

“Why aren’t there any track and field people in here?” Lyles wondered.

“Obviously it’s not happening because we aren’t doing it,” he said, answering his own question. “But why aren’t we doing it?”

His mind works as fast as his feet. Surely he could make it happen. Maya Bruney, a former sprinter, was right there with him. In November 2022, she created Track and Fits, on Instagram, and it has become the sport’s equivalent to the popular LeagueFits, a place where, that site says, “hoop and its lifestyle collide.”

The New Balance Indoor Grand Prix in Boston on Feb. 4 would be a testing ground. Lyles arrived to the track wearing what he described as a “Men in Black” outfit, one that garnered flame emojis on Instagram from a who’s who of the world’s top runners. The sprinter Trayvon Bromell walked in wearing snakeskin pants. The American Olympian Aleia Hobbs showed up wearing Louis Vuitton sunglasses and a white puffer coat.

Lyles organized another walk-in at the Millrose Games in New York City a week later. A few athletes signed on again, and he fielded a lot of questions from those intrigued by the idea, if not intimidated by it.

“I had to explain what the idea was to a lot of athletes, which I thought was going to be the easiest part, because everyone watches the N.B.A. and N.F.L.,” he said. “But I guess I’m the only one that pays attention.”

By the time the Atlanta City Games rolled around in May, Lyles was a one-man event planner. He organized a location with meet directors, secured proper changing areas, directed photographers to their spots and made sure vehicles — no team vans, only black cars, he said — dropped athletes off in the right spot.

Lynna Irby-Jackson, Gabby Thomas, Freddie Crittenden, Noah Williams and Anna Hall entered the venue wearing clothes that were decidedly not for warm-up drills.

“It’s really good for the sport,” Thomas, a two-time Olympic medalist, said. “Any time you can do something that can support and promote track and field as a whole, I’ll be there to do it.”

This month, at the Diamond League event in Florence, Italy, Hall, Joseph Fahnbulleh and Tara Davis-Woodhall followed suit. Both the U.S.A.T.F., the sport’s governing body in the United States, and World Athletics have lent their support.

So why is this happening now, especially in a sport that has long sought to attract attention in non-Olympic years?

“It’s social media,” Sanjay Ayre, a retired sprinter, said on Saturday at the N.Y.C. Grand Prix. He strode up to a V.I.P. tent wearing an oversize Balenciaga raincoat, Balenciaga shoes and a bucket hat. It was not like this when he competed for Jamaica in the early 2000s, he said.

Indeed, the crossover was seen on Paris Fashion Week catwalks a few days before the New York meet. Wales Bonner chose the Ethiopian distance runners Yomif Kejelcha and Tamirat Tola to model a spring 2024 collection called Marathon.

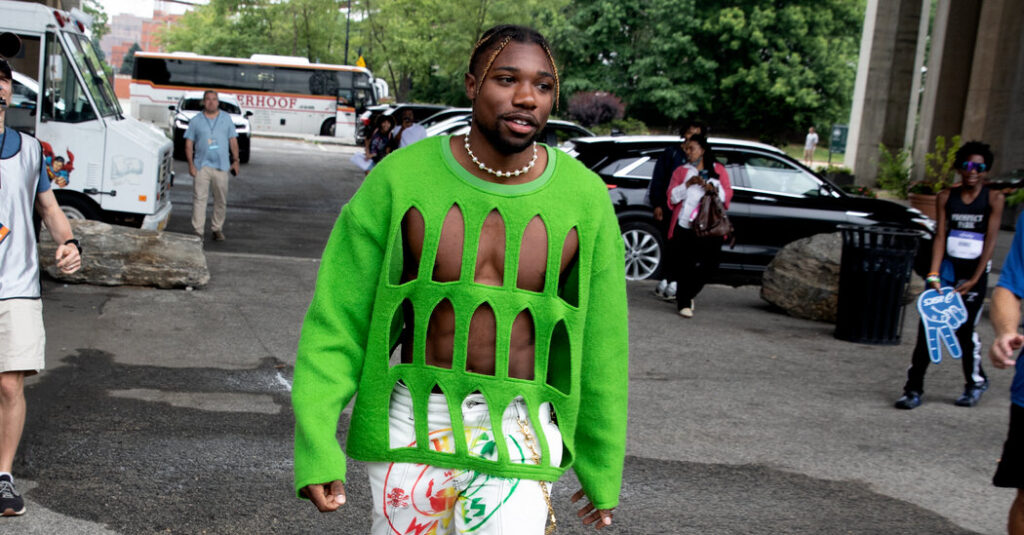

On Friday afternoon, Kwasi Kessie, Lyles’s stylist, brought a few outfits to his Midtown Manhattan hotel. Lyles quickly chose a Who Decides War top, a green sweater with windowlike holes throughout the silhouette — because nobody’s bold enough to wear it, he said. He scoffed at a suggestion of wearing a shirt underneath it. “I work out 365 days for a body like this,” he said. “We don’t need no shirt.”

Lyles and his agent, Mark Wetmore, had already invited a handful of athletes to join them for the walk-in at the N.Y.C. Grand Prix. They expected a mix of some of the biggest names in the sport to participate: Christian Coleman, Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone, Athing Mu, Thomas and Devon Allen.

But in the hours before the event on Saturday, it became clear that Lyles would be the only athlete doing the 30-meter walk-in. Media obligations and scheduling conflicts were blamed for the no-shows.

When the other athletes saw what happened when Lyles arrived, they might have wished they had adjusted their schedules.

About noon, a handful of men with walkie-talkies and earpieces started organizing a growing crowd of fans with foam fingers and notepads ready for autographs. “His E.T.A. is now 12:21,” one said to the other as two security guards took their places.

Right on cue, a black S.U.V. appeared next to an ice cream truck. Lyles stepped out of the car wearing Who Decides War pants, featuring palm trees and waves, and Timberland boots. Dozens of fans craned their necks to get the best view and squealed at the sight of him. Cameras recorded every step. Fans pressed pens and posters into his hands and jumped in delight when he signed them. Completely wrapped in adulation, he could barely take a step forward.

In a few hours, Lyles won the 200 meters with a time of 19.83 seconds.

But in this moment, he had already arrived. He was just working to bring his sport along with him.