Beta blockers have long been widely prescribed for patients with heart issues, but two new studies this week question the benefit of the therapies in certain patients with strong heart function.

One study, published Tuesday in Heart, looked at people who experienced a heart attack but didn’t develop heart failure or dysfunction in their heart’s pumping. Researchers found that long-term beta blocker use wasn’t associated with improved cardiovascular outcomes in this group.

The other study, published Wednesday in JACC: Heart Failure, focused on people with heart failure who had mildly reduced and normal ejection fraction, which is a measure of a heart’s squeezing function. The authors found that beta blockers were linked to a greater risk of hospitalization in patients with higher squeezing power.

Beta blockers lead the heart to beat more slowly and are meant to lower stress on the heart. Doctors have been prescribing the medications based on data from decades ago before recent advancements in cardiovascular care, and patients also often have comorbidities that lead doctors to prescribe beta blockers. While the two studies are both observational, and the authors stressed the need for more research that follows patients over time, the findings still suggest that the longstanding practice of prescribing beta blockers merits reassessment.

The data are “all pointing to a similar direction that not all patients that we used to historically reflexively put on beta blockers benefit from beta blockers,” said Lakshmi Sridharan, an advanced heart failure and transplant cardiologist at Emory University who wasn’t involved in the studies.

“Now is the time to be personalized and individualized in our decision-making” on patients’ treatment plans, she said.

The study in Heart analyzed health records from over 43,000 adults in Sweden who experienced a heart attack but didn’t have heart failure or pumping dysfunction. While there’s research supporting the use of beta blockers shortly after a heart attack in these types of patients, there’s little data looking at longer-term use, so the researchers focused on beta blocker usage one year after a heart attack.

Of the patients studied, a majority of them — 79% — were on beta blockers a year after a heart attack. After adjusting and weighting for factors such as demographics and comorbidities, the researchers found no difference in the risk of death and cardiovascular incidents between people who were and weren’t on beta blockers during a median follow up of 4.5 years.

Gorav Batra, the senior author and consultant cardiologist at Uppsala University in Sweden, said the care and treatment of patients with heart attacks has vastly improved over the last three decades. That means patients experience less injury to their heart muscle from heart attacks, and so they may not need beta blockers long term to help them.

Sridharan noted that since the study was conducted in Sweden, its findings may not be generalizable to the U.S. population.

Still, she said, it’s important to examine the use of beta blockers since heart attack care has advanced and since the drugs can come with side effects that affect patients’ quality of life, such as fatigue and depression. “That’s when the question of the risk-benefit ratio really comes into play for these patients,” she said.

The other study published in JACC: Heart Failure looked at over 400,000 people in the U.S. over the age of 65 who had heart failure with mildly reduced or normal squeezing function, described as an ejection fraction greater than 40%.

While studies have consistently shown the benefit of beta blockers in heart failure patients with significantly reduced squeezing power, measured as an ejection fraction less than 40%, there’s limited data on use of the drugs in people with stronger squeezing function.

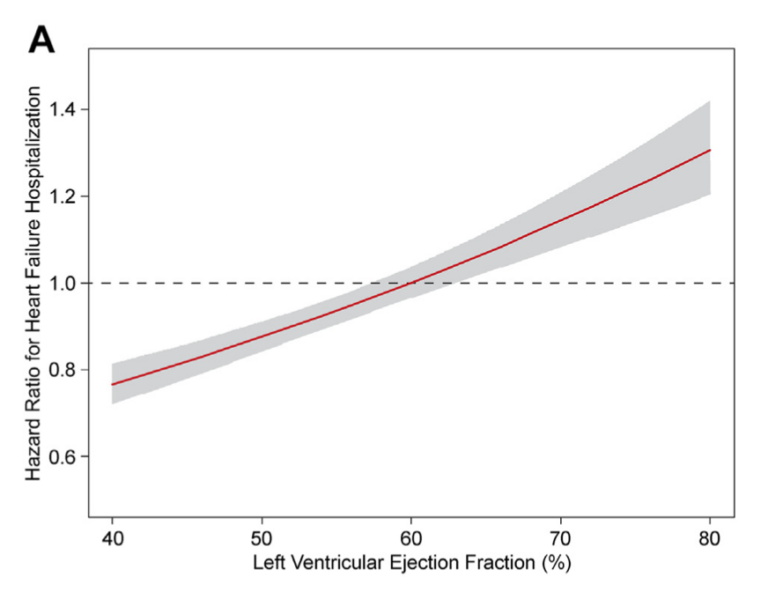

Yet again here, most patients studied — 66% — were on beta blockers. After adjusting for factors like comorbidities and health history, and in a median followup of 38 months, the researchers found that as the ejection fraction number increased, the risk of hospitalization for heart failure linked to beta blocker use also increased.

Among patients with a mildly reduced ejection fraction, beta blockers were associated with a lower risk of hospitalization and death. But among patients with greater squeezing function, particularly those with an ejection fraction over 60%, beta blockers were linked to higher hospitalization rates.

The researchers also found that this trend held whether or not patients had hypertension, an irregular heartbeat, or coronary artery disease — which are three comorbidities that currently lead doctors to prescribe beta blockers.

The study suggests “you really have to pay attention to what the ejection fraction is” when treating heart failure patients, said Suzanne Arnold, the lead author and a professor of medicine at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Michelle Kittleson, director of heart failure research at the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, said the studies show the importance of reviewing the medications each patient is on and justifying their need.

While beta blockers have been around for a long time, there hasn’t been much research probing their utility for various patient groups.

“That’s inertia in medicine — it’s very hard to stop a medicine, it’s very hard to say no, it’s very hard to backtrack,” Kittleson said. “It takes a lot of activation energy to do a deep dive and figure out if something is needed.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.