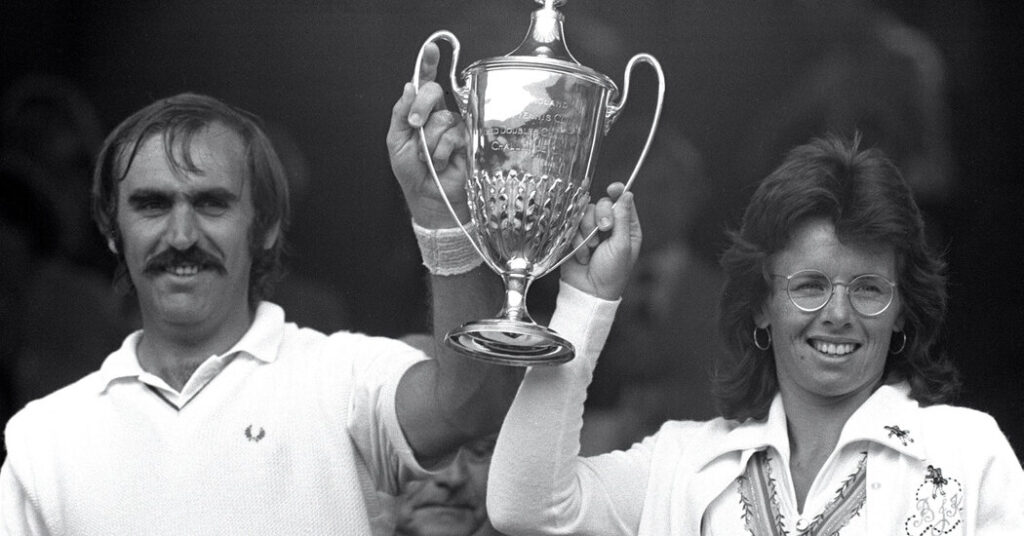

Owen Davidson, an Australian tennis player who formed a dominant mixed doubles team with Billie Jean King in the 1960s and ’70s, winning eight Grand Slam titles with her, along with five doubles titles with other partners, died on Friday in Conroe, Texas, a suburb of Houston. He was 79.

The cause was cancer, his longtime friend Isabel Suliga said.

Davidson came of age during a heyday for Australian tennis, with peers like Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, Roy Emerson, John Newcombe and Margaret Court.

Unlike those players, Davidson did not have significant success in singles tennis, never advancing beyond the semifinals of a Grand Slam tournament. But his congeniality, sportsmanship, lob-inducing serve and adroitness in volleys made him one of the sport’s strongest doubles players.

From 1965 to 1974, he won 11 major mixed doubles titles and two men’s doubles titles. In 1967, he swept every major mixed doubles event, winning the Australian Open with his countrywoman Lesley Turner Bowrey and then winning the French Open, Wimbledon and the U.S. Open with King.

Davidson and King trained together starting in 1964 in the suburbs of Melbourne with the Australian great Mervyn Rose. On her first day in camp, King felt sent around the court “like a pinball” fielding shots from Davidson, she recalled in her 2021 autobiography, “All In.”

“I’ve always said the Australian men made me No. 1, and those sessions were an important part of it,” she wrote.

The duo won their first Grand Slam in 1967 at the French Open.

“I played mixed with so many great players, but I couldn’t win with the others,” King recalled in a phone interview, mentioning leading men she had partnered with, like Newcombe and Dennis Ralston.

She and Davidson, conversely, struck a harmonious balance between her optimism and competitiveness and his steadiness and modesty. “He wasn’t Mr. Exuberant,” she said. “He’s more Steady Eddy.”

Davidson’s athletic strengths included his powerful overhead on his weak right side; his serve, which King compared to a cricket bowler’s delivery; and his team play at the net.

“He let me take a lot of volleys that most guys would not,” King said. “They would get in and try to take the volley first.”

That was particularly useful during the duo’s epic face-off against Court and Marty Riessen at Wimbledon in 1971.

Davidson and King lost the first set 3-6 and won the next one 6-2. The final set remained undecided after 27 games.

“We all four would be at net, just pounding away at each other,” King said.

Wimbledon’s rules then stipulated that a final set had to be won by two games. King saw the sun beginning to set, threatening to delay the conclusion of the match to the next day.

“I said to him, ‘Owen, we have to finish this, we cannot wait until tomorrow,’” King recalled. “I’m kind of the cheerleader. He said, ‘OK. Let’s go.’”

Davidson and King won the final set 15-13.

Owen Keir Davidson was born on Oct. 4, 1943, in Melbourne.

As a singles player, he won the first game of the so-called Open Era, when the major tennis tournaments welcomed both amateurs and professionals.

In that game, in April 1968 at the West Hants Tennis Club of Bournemouth, a town on the coast of southern England, Davidson, who was a pro, beat the British amateur John Clifton, 6-2, 6-3, 4-6, 8-6. He lost in the quarterfinals to Rosewall.

He also reached the Wimbledon semifinals in 1966, upsetting Emerson but losing to the Spanish player Manuel Santana.

Davidson’s first marriage, to Angie Davidson, ended in divorce. His second marriage, to Arlene Davidson, lasted about 20 years, until her death about a decade ago.

He is survived by his son from his first marriage, Cameron, and a brother, Trevor. He lived near Conroe in The Woodlands, a planned community whose country club Davidson had worked at as a tennis pro on and off since 1974.

With King lobbying on his behalf, Davidson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 2010.

Every time King called Davidson, he seemed to be watching Tennis Channel. “What do you think of this player or that player?” she recalled him asking. He had, King said, “a good eye for who was going to do well and who wasn’t.”