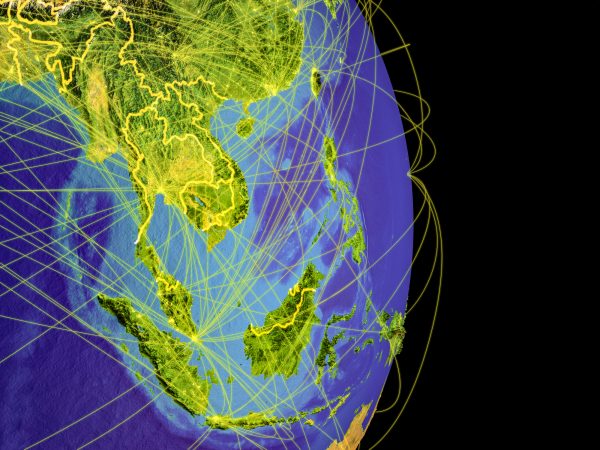

With nearly 700 million people and rapidly growing economies, Southeast Asia has become a pivotal region in the global geopolitical landscape. The technological revolution sweeping across its diverse nations is reshaping traditional industries and governance structures at an unprecedented pace. As digital innovation accelerates, Southeast Asian countries are strategically positioning themselves to maintain sovereignty over their technological futures while fostering vibrant innovation ecosystems amid intensifying global tech rivalries amongst states and their respective firms. At a time when a multipolar world order is characterized by intensifying strategic competition and fluid geopolitical realignments, the imperative for the region to develop autonomous technological infrastructure and digital sovereignty has never been more critical.

The total digital economy of Southeast Asia is projected to hit $1 trillion by 2030. This exponential growth is underpinned by the rapid deployment of advanced telecommunications infrastructure, including 5G networks, fiber-optic backbones, and edge computing nodes across urban and rural territories. The proliferation of machine learning applications, generative AI implementation, and cloud computing architectures forms the material substratum enabling unprecedented data processing capabilities throughout the region.

Southeast Asia has added tens of millions of new internet users in recent years, creating fertile ground for e-commerce, digital finance, and super-app ecosystems. Reports by the World Economic Forum further highlight that despite current challenges, Southeast Asia’s digital market is poised for transformative expansion as both public and private sectors collaboratively invest in digital infrastructure, regulatory frameworks, and cross-border data governance mechanisms to harness the region’s vast digital potential.

Critically examining the complex topography of this technological landscape and unravelling the socio-political implications of these digital transformations is imperative for understanding how Southeast Asia is navigating its technological future amid competing global influences.

The Planetary Regime of Data Extraction

Globally, 68 percent of data centers are controlled by U.S. and European giants. This list includes hyperscalers like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud from the U.S., alongside European providers like OVHcloud and Deutsche Telekom. By the same count, Asia, including China, accounts for 26 percent of global data center infrastructure. This concentration of digital capability and infrastructure has sparked warnings of “digital colonialism,” where immense data generated flows offshore to the old industrialized developed countries.

“Control over data is a question of national sovereignty,” Johnny G. Plate, Indonesia’s then-minister for communication and information technology, said in 2022.

The stakes are existential. Southeast Asia’s internet users are set to reach 402 million this year, generating vast troves of security, health, financial, and biometric data. Most of this data is stored in Big Tech’s global data infrastructure. Yet, under laws like the U.S. CLOUD Act, and Europe’s data protection regulations, U.S. and European countries can utilize this data through legal frameworks, while simultaneously being compelled to grant access to foreign governments upon official request.

In their book “The Cost of Connection: How Data is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating it for Capitalism” (2022), Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias affirm this asymmetrical structural relationship but tie it to the historical core-periphery dynamics in which Southeast Asia finds itself embedded. Their genealogy of this relationship demonstrates that colonial power structures are being reconstituted under the guise of digital innovation and AI advancement. Historical colonial relations that once extracted natural resources and labor from the Global South are now manifesting in the digital realm, with data extraction replacing physical commodities while maintaining similar patterns of value transfer and power asymmetry.

This technological neo-colonialism presents multiple threats to regional sovereignty. This includes economic dependency where the most valuable components of the digital value chain remain controlled by foreign entities and utilized for economic, social, military, and political gains. There is also the unprecedented surveillance capability giving U.S. and European governments and corporations access to sensitive information. Finally, this process undermines cultural and social sovereignty through algorithmic systems that prioritize Western cultural norms.

But this hegemonic relation and process is slowly being questioned if not rejected. A few examples serve to demonstrate the region’s “desire to be self-reliant.” In 2022, Vietnam’s government quietly passed a law requiring Facebook, Google, and other foreign tech firms to store user data locally. Similarly, Indonesia’s digital nationalism policies aim to retain data within national borders, while the Philippines has established a national AI strategy explicitly designed to prevent foreign dependency. Malaysia has also invested in sovereign cloud infrastructure.

These policies are emblematic of the region’s response to fears of foreign surveillance, political control, and economic exploitation. They underscore a growing realization in the region that data is the oil of the 21st century, and that Southeast Asia risks pumping its reserves into foreign tanks.

Yet despite these efforts, no Southeast Asian country has successfully broken free from the digital and economic dependency established under Big Tech’s oversight. The immense capital requirements for building sovereign digital infrastructure, combined with technical expertise concentrated in Silicon Valley and Shenzhen, have created structural barriers that perpetuate digital dependency across the region, despite growing awareness of its sovereignty implications. But there are signs that this may change in certain pockets in the region.

Building Fortresses: Southeast Asia’s Data Center Boom

The region is experiencing a decisive shift toward data localization and native digital infrastructure development. This strategic recalibration of digital governance frameworks reflects growing recognition of data sovereignty as a cornerstone of national security and economic autonomy. The region’s policymakers are increasingly implementing regulatory mechanisms that mandate territorial control over critical information assets while simultaneously cultivating domestic technological capabilities to reduce dependency on foreign digital infrastructure.

As part of this movement recently, Singapore, long a regional tech hub, has emerged as a pioneer. Its AI Singapore initiative, launched in 2017 with $500 million in funding, pairs cutting-edge research in healthcare and finance with strict data residency rules. Public sector data must be stored in local centers, a policy that attracted companies like Google Cloud to build infrastructure while complying with Singapore’s privacy laws.

Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, took a tougher stance. Its 2022 Personal Data Protection Law mandates that public data reside domestically, a rule that pushed Amazon Web Services to open a Jakarta data center last year. The law is part of Indonesia’s “Making Indonesia 4.0” strategy, which uses AI to tackle challenges from crop failures to disaster response.

Smaller economies are following suit. Vietnam’s Decree 53, enacted in 2022, requires social media platforms to store user data locally – a move that forced TikTok to lease server space in Hanoi. Thailand, meanwhile, is collaborating with Japanese firms to build hyperscale data centers in Bangkok, aiming to become the AI hub of the Mekong region.

Even Malaysia, which has historically relied on foreign cloud providers, is pivoting. A $15 billion initiative called MyDigital is migrating government data to local servers, while a partnership with Nvidia aims to develop homegrown AI tools for manufacturing. “This isn’t about rejecting foreign investment,” said Malaysian Digital Minister Gobind Singh Deo. “It’s about ensuring our data generates jobs and innovation here, not just in Silicon Valley.”

Big Tech and large firms in the region have sought to misrepresent this trend toward self-reliance, autonomy, and digital resilience as regulatory processes that will “damage innovation.” This is far from the case. Most of these initiatives strengthen national security by preventing unauthorized access to critical data, reduce latency for local users, and create high-skilled jobs in the domestic technology sector.

These policies enable greater regulatory compliance with local cultural values and legal frameworks while allowing countries to retain the economic value of their citizens’ data rather than seeing it extracted by foreign entities. Data localization also empowers governments to implement AI solutions specifically tailored to regional challenges like disaster management and agricultural productivity without dependence on external decision-making.

A Future Forged Locally

The message from Southeast Asia’s leaders is clear: Data is power, and power must remain at home. Indonesia’s minister for communication and information technology emphasized in a 2022 speech that “digital sovereignty is a key step in strengthening the country’s independence.”

As China-U.S. tensions fracture the tech world into competing blocs, Southeast Asia has a narrow window to chart its own course. Building data centers alone isn’t enough; the region must cultivate talent, craft ethical guardrails, and demand fair terms from global giants. The alternative – ceding control of the digital future – is a risk no nation can afford. As Vietnam’s Minister of Information Nguyen Manh Hung bluntly stated: “If you don’t own your data, you don’t own your destiny.”

Couldry and Mejias’ analysis has proven prescient. Today’s data extraction perpetuates historical patterns of colonialism, only now with algorithms and data centers instead of armies and barracks. The region recognizes that breaking free from this digital dependency requires not just infrastructure, but reimagining the entire relationship between technology, sovereignty, and regional cooperation.

For Southeast Asia, technological independence isn’t merely an economic strategy – it’s the foundation of true sovereignty in the digital age.