As one of the most primitive parts of our nervous system, the vagus nerve controls many aspects of … [+]

As one of the most primitive parts of our nervous system, the vagus nerve controls many aspects of the body that are outside our conscious control. From eating to breathing to making sure our hearts never miss a beat, the vagus nerve extends into every major organ. Understanding how the vagus nerve functions may offer new insights into treating chronic conditions. As part of our new series on the various functions of the vagus nerve, we will examine how devices that directly stimulate this nerve may be able to reverse chronic inflammation.

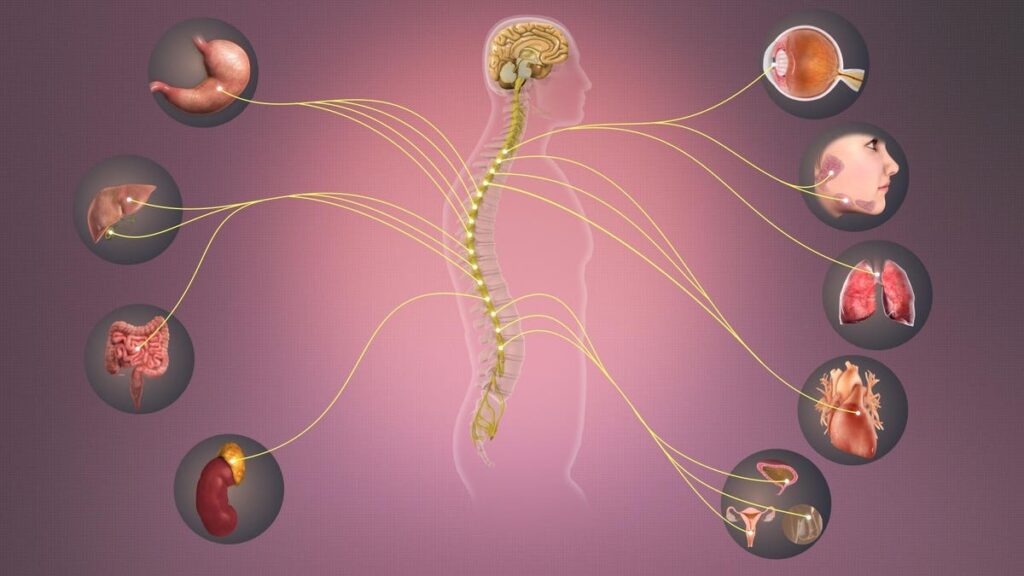

The vagus nerve does not consist of a single nerve, but rather a bunch of nerves that connect the brain to the rest of the body. Originating from a region of the brainstem known as the medulla oblongata, this bundle of nerves extends through the spinal cord and branches out into the chest and abdomen. The vagus nerve acts as a bidirectional highway through which the brain and body communicate with each other. Afferent nerves transmit signals from the body to the brain, and in response, efferent nerves relay instructions from the brain to our organs.

As a key component of the autonomic nervous system, the vagus nerve has four primary functions: sensory, special sensory, motor and parasympathetic. Many of the vital functions outside of our conscious control, such as heart rate, digestion, and breathing, are controlled by the vagus nerve. In response to stress, stimulating this nerve can decrease heart rate, lower blood pressure, and boost digestion.

Dr. Kevin Tracey and his colleagues at the Northwell Health’s Feinstein Institute were the first to find that the vagus nerve can also regulate inflammation. This nerve seems to be a key conduit of the inflammatory reflex system that recruits immune cells to fight infection. When a foreign pathogen invades the body, for example, the innate immune system responds by producing cytokines and other immune cells to localize the infection. These inflammatory cells stimulate the vagus nerve to tell the brain to direct more resources to the infection site. Once the infection subsides, the vagus nerve suppresses the immune system to return the body back to homeostasis. The intensity of inflammation seems to be controlled by the vagus nerve. When this nerve is severed, as studies have observed in mouse models, the body’s innate immune response can become too great and damage otherwise healthy cells.

Although temporary inflammation is good when the body is actively fighting an infection, chronic activation of the immune system can have devastating consequences. Dysregulation of the innate immune system has been shown to underlie several chronic diseases, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer’s, and gut-related disorders. Not to mention, many of the long lasting complications associated with COVID-19 infections result from a robust activation of the immune system.

Given its role in the inflammatory reflex, chronic inflammation seems to correlate with decreased vagal nerve activation. Without suppression from this nerve, the immune system continues attacking itself, making you feel worse. Using electrical impulses to stimulate the vagus nerve, therefore, presents a new opportunity for treating chronic diseases.

Vagal nerve stimulation can be applied using a small, electrical device that is surgically placed … [+]

Vagal nerve stimulation has already been tested in clinical trials and approved by the FDA for treating epilepsy and mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety disorders. For individuals that have not been responsive to other treatments, a small, electrical device can be surgically placed under the chest, similar to a pacemaker. A thin wire stretches up to the neck where mild electrical impulses can be transmitted directly to the vagus nerve throughout the day. The FDA has also recently approved newer non-invasive vagal nerve stimulators to treat cluster headaches and migrants without surgery.

Increasing studies now suggest that vagal nerve stimulation may be a viable treatment option for some chronic inflammatory conditions. An early clinical trial for treating rheumatoid arthritis, for example, confirmed that electrically stimulating the vagus nerve was not only well tolerated but also significantly reduced symptoms to a similar effect as pharmacological interventions.

In this study, a miniature vagal nerve stimulator was surgically implanted under the skin of 17 individuals with early and late stages of rheumatoid arthritis, 7 of whom had not responded to previous treatment. The device administered a 2.0 mA electrical current to the left vagus nerve for 60 seconds four times a day. This electrical stimulation was strong enough for individuals to feel but not cause any pain. Over the span of 84 days, the study participants underwent periods of active and inactive stimulation.

All individuals reported reduced symptoms while they were receiving daily electrical impulses to the vagus nerve. During withdrawal periods, however, inflammatory symptoms seemed to return. Koopman et. al observed that restarting the treatment remained effective in alleviating symptoms, further confirming that the vagus nerve plays a vital role in modulating the inflammatory system. Investigators also found the clinical benefits of vagal nerve stimulation correlated with a decrease in tumor necrosis factor (TNF), an inflammatory protein that exacerbates the immune system and damages the joints of individuals with arthritis. This was one of the first studies in humans to show that inflammation could be controlled by stimulating the vagus nerve.

Recent vagal nerve stimulation studies have also been successful in reducing the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, another chronic condition characterized by excessive inflammation. One study, for example, followed nine individuals with Crohn’s disease that underwent continuous vagal nerve stimulation over the course of a year. Six of these individuals were able to achieve “healthy” colon profiles that were no longer burdened by inflammation. The improvement of their symptoms correlated with decreased inflammatory biomarkers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and fecal calprotectin that disrupt the gut microbiome. Given that inflammation can affect multiple organs simultaneously, this novel therapeutic approach could be used to treat multiple conditions at once.

There are, however, considerable questions that remain unanswered. How long would an individual have to wear the device to maintain relief from symptoms? Do its benefits eventually wear off as the body habituates to the electrical simulation? And, can vagal nerve stimulation serve as a cure for some conditions or is it simply an immunosuppressant? The answers to these questions can only be answered by additional clinical trials. Understanding the many roles of the vagus nerve gets us one step closer to finding new therapeutic targets for a range of diseases.