Ever since fentanyl came to dominate the U.S. illicit drug supply, doctors and patients have found buprenorphine, a key addiction-treatment medication, increasingly difficult to use.

All too often, fentanyl’s potency has meant that patients transitioning to buprenorphine, a far weaker drug, experience excruciating symptoms known as “precipitated withdrawal.” Often, the discomfort is so severe that patients give up on buprenorphine altogether.

But a trio of West Coast doctors is reporting a buprenorphine breakthrough thanks to an unlikely-seeming medication: ketamine, an anesthetic used both medicinally and recreationally and that has hallucinogenic effects at high doses. Giving tiny doses of ketamine as patients begin buprenorphine treatment, they say, has all but eliminated their withdrawal symptoms.

“People were coming in having been traumatized by precipitated withdrawal experiences, and very wary about getting onto buprenorphine,” said Cindy Grande, an addiction doctor in Washington state who has used ketamine to help over a dozen patients transition onto buprenorphine. For those patients, she said, the addition of ketamine is “like a miracle.”

The discovery of ketamine as a potential addiction-treatment aid highlights a current crisis. Currently, there are only two drugs approved to treat withdrawal symptoms and opioid cravings: methadone and buprenorphine. And with more than 80,000 Americans dying of opioid overdose each year, there has never been a greater need for medication-based treatment.

Methadone, however, is only available at specialized clinics. And while buprenorphine — often referred to by a common brand name, Suboxone — can be prescribed by any doctor, it is increasingly associated with painful withdrawal symptoms. Sometimes, that discomfort is so severe that patients give up on buprenorphine altogether and resume using illicit drugs, despite their desire to stop.

“Standard approaches to buprenorphine in the fentanyl era can leave patients feeling like we’re throwing penicillin at a superbug,” said Thomas Hutch, a Seattle-area addiction doctor who has collaborated with Grande to offer patients ketamine as they begin addiction medication. “Getting onto bupe is rough, but it shouldn’t be so rough that they feel like our concern for their comfort is in question. That’s where the ketamine comes in.”

The ketamine approach is just the latest example of doctors getting creative with the process of beginning buprenorphine treatment, also known as buprenorphine “induction.”

In response to fentanyl’s potency and seemingly precipitated withdrawal, some doctors have begun giving buprenorphine doses far larger than they did a few years ago. Others have employed the opposite approach: “microdosing” buprenorphine over the course of several days in an effort to reduce discomfort while encouraging patients to slowly reduce illicit drug use. Some have even offered patients the bold, painful approach of using naloxone, the drug used to reverse opioid overdoses, to intentionally begin withdrawal — then using a large buprenorphine dose to end it.

Ketamine’s advocates, however, say that the medication offers a simpler means of beginning treatment. So far, the medical community has responded with enthusiasm.

Grande, Hutch, and Andrew Herring, an Oakland, Calif.-based addiction doctor, received rave reviews after presenting the ketamine approach last month at the American Society of Addiction Medicine’s annual conference.

The trio, Hutch said, came together naturally. Herring, who is also an emergency physician, had experience using ketamine to help with buprenorphine inductions in inpatient settings. Grande had previously used ketamine to treat pain and depression. And Hutch, the medical director of an opioid treatment program, had a large pool of patients who stood to benefit from ketamine, and sent many of them Grande’s way.

While promising, positive results from the ketamine-buprenorphine combo are limited to a tiny population. The doctors’ findings are largely observational: No randomized trial has been conducted, and there is little existing medical literature on the practice. (One 2021 paper, on which Herring is listed as a co-author, detailed a single instance of a patient whose severe withdrawal symptoms were alleviated with intravenous ketamine.)

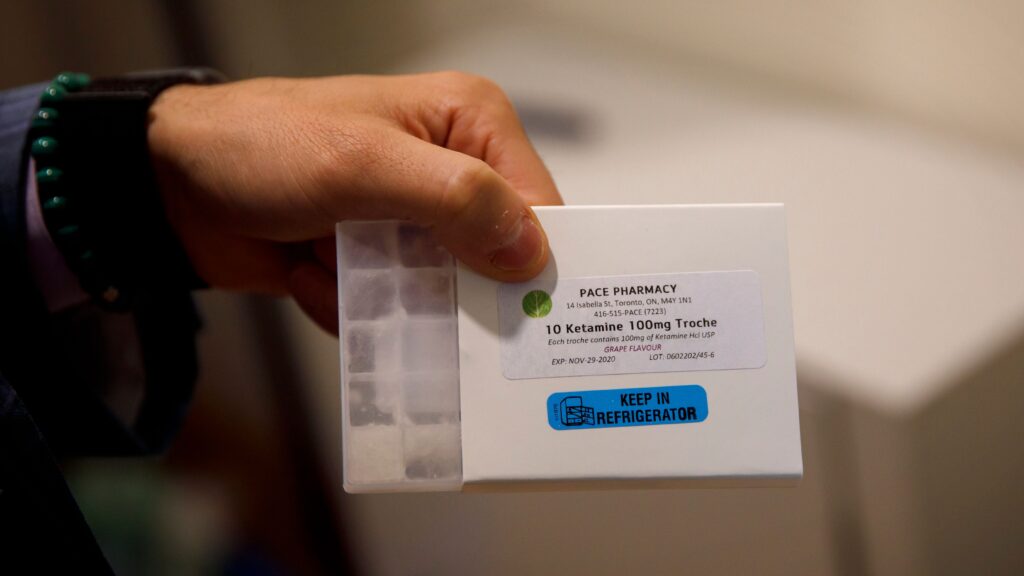

Still, the approach is highly promising. Ketamine is not an experimental medication, and doctors are largely free to prescribe it to any patient. Moreover, Grande said that the dosage of the ketamine lozenges she uses to aid buprenorphine treatment are tiny — between 1% and 2% the size of what she called “a typical anesthetic dose.”

The strategy is so new, however, that the doctors are still divided on exactly why it’s so effective. One straightforward theory is that ketamine has anesthetic and sedative properties — the perfect treatment for withdrawal. Hutch, however, is skeptical, arguing that the dose is simply too small to have any pain-alleviating effect.

Hutch’s theory centers on the incredibly high opioid tolerance that fentanyl users often develop, which results in once-standard buprenorphine doses feeling inadequate. But ketamine, he said, essentially magnifies buprenorphine’s effect — making a once-inadequate dose sufficient.

“You could think of it like a buprenorphine amplifying agent,” he said.

The doctors also have not yet settled on a consistent protocol for ketamine’s use: In some instances, ketamine is used to treat withdrawal symptoms after an initial buprenorphine dose, while in others, it’s taken as a preventive measure, meant to prevent withdrawal symptoms entirely.

But in either scenario, Grande said, the results have been astonishing.

“The very first patient I treated with this had been in precipitated withdrawal for 18 hours,” she said. “I provided her 16 milligrams, but she and her mother were nervous about taking the whole thing. So she took a quarter of it, 4 milligrams, and that was all it took. She felt fine within five minutes.”

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.