March 15 (Reuters) – With just six days to go before Federal Reserve policymakers sit down in Washington, exactly what decision they’ll make on interest rates now and in coming months has become pretty much anyone’s guess, and investors and Wall Street economists are doing just that.

Over the past year, Fed leadership has gone out of its way to signal its intentions on interest rate hikes aimed at quashing hot inflation, relying on a steady stream of economic data inputs to guide its actions.

But now Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues find themselves needing to respond in real time to turmoil in the banking system after the collapse of two large regional U.S. banks and Swiss regulators having to pledge assistance to Credit Suisse, developments that are reshaping domestic and international financial conditions on a daily – or even hourly – basis.

In one of the most vivid – and relevant – examples, on Monday the yield on the 2-year Treasury note , among the top traded securities in the world that also stands as a proxy for Fed policy expectations, plummeted by more than half a percentage point, the most since the day after Black Monday in October 1987. It then recovered roughly half that on Tuesday only to drop by another third of a point on Wednesday.

And it is all unfolding during the central bank’s premeeting blackout period that prevents officials from offering public clarity on their assessment of the situation, and its effect on monetary policy decisions

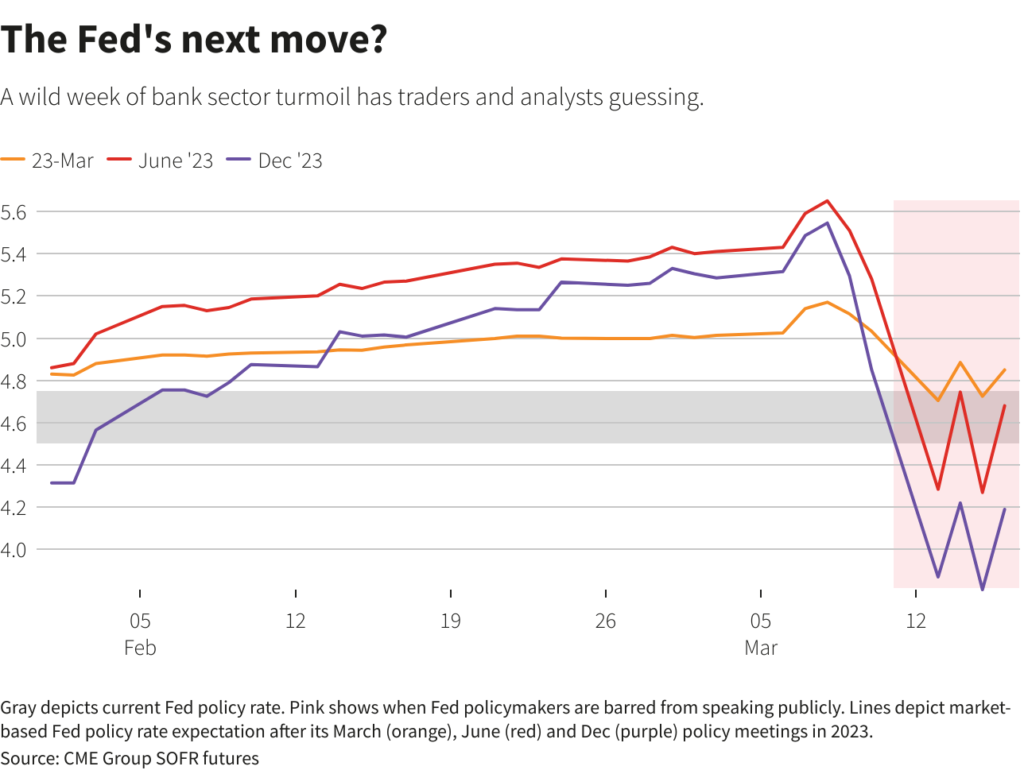

It was only last week that Powell signaled the central bank might accelerate its interest-rate-hike campaign in the face of persistent inflation. Traders moved to price in a half-point hike in the benchmark interest rate at the Fed’s March 21-22 meeting, from its current 4.5%-4.75% range, and further rate hikes beyond.

Traders now see next week as a tossup between a smaller quarter-point hike and a pause, with rate cuts seen likely in following months as the turbulence at Credit Suisse renewed fears of a banking crisis that could cripple the U.S. economy.

Analysts also sought to make sense of fast-moving events, including Friday’s failure of Silicon Valley Bank, the creation over the weekend of an emergency Fed backstop for the banking sector, fresh data showing slow progress in the inflation fight, and a renewed banking stock swoon on Wednesday.

“I think they do indeed hike 25 bps next week,” said Jefferies’ Thomas Simmons. “They need to keep up the fight on inflation to maintain credibility, and a pause here at these levels isn’t going to stop the bleeding in the markets.”

A pause, he argued, risks undoing the work of the Fed’s 4.5 percentage points of rate hikes since last March.

“They’d also risk sending a signal to the market that the macroeconomic impact of these microeconomic phenomena is worse than we think,” he said.

Former Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren took the opposite view.

“Financial crises create demand destruction,” Rosengren said on Twitter. “Banks reduce credit availability, consumers hold off large purchases, businesses defer spending. Interest rates should pause until the degree of demand destruction can be evaluated.”

WILD SWINGS

At heart, the uncertainty over the Fed’s next move comes down to difficulty knowing how swiftly and deeply the current turmoil in the banking sector will filter through to the real economy.

After all, the Fed’s rate hikes are designed to slow the economy, and for months some policymaker have expressed puzzlement over why after such aggressive policy tightening there was so little of that to see beyond the sharply-hit housing sector.

After the bank failures in recent days, “We’re getting a better sense of who’s suffered due to the Fed’s aggressive tightening,” JPMorgan’s Michael Feroli wrote. Slower growth in lending by mid-size banks will sheer off a half to a percentage point of economic growth overall, he predicted, “broadly consistent” with the view that higher interest rates will trigger a U.S. recession that will in turn slow inflation.

But the Fed’s work in Feroli’s view is not yet done.

A key inflation report earlier this week showed a 6% rise in the consumer price index last month from a year earlier.

“A pause now would send the wrong signal about the seriousness of the Fed’s inflation resolve,” Feroli said.

The Fed next week will publish new projections for the future path of the U.S. benchmark rate. In December policymakers had seen it topping out at 5.1%, and as recently as last week traders expected it to rise above 5.5%.

Now, they are looking for one more Fed rate hike if that, and then a string of reductions to bring the target range down below 4% by year end.

“The Fed has a very difficult policy decision to make at next week’s meeting,” said Paul Ashworth, chief North America economist at Capital Economics, which for now still leans towards the Fed raising interest rates by a quarter percentage point. “It is a very close call… the risk of a full-blown contagion remains, and a lot can happen in the week until the announcement.”

Reporting by Lindsay Dunsmuir and Ann Saphir; Editing by Chizu Nomiyama, Andrea Ricci and Dan Burns

: .