Eleni Tsigas likens her first experience with preeclampsia to a plane crash. She was in the midst of what she thought was a healthy first pregnancy, with low risk for complications. But at 29 weeks, she was rushed to the emergency room with what she now knows are classic signs of preeclampsia: very high blood pressure, a pounding headache, nausea, blurred vision. She lost her first child while being transported between hospitals.

“When they debrief plane accidents, there’s usually 13 different things or 15 different things that led to the accident. It’s rarely just one,” said Tsigas, now the CEO of the Preeclampsia Foundation, a patient advocacy group.

To equip both clinicians and patients with the tools to prevent these tragedies, a group of experts including Tsigas have developed a new, evidence-based preventive care plan for those who are at moderate to high risk of preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication that can drive blood pressure dangerously high and is a leading cause of maternal and infant deaths. The care plan, published Friday in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, recommends a range of interventions to lower a patient’s risk, including at-home blood pressure checks, treatments like low-dose aspirin, and continuing to take any other needed heart medication, which people are often wary to do when pregnant. The plan also includes lifestyle recommendations for patients like eating a Mediterranean diet, exercising, and getting at least 7 hours of sleep per night.

Those aren’t novel recommendations, but the authors say it’s the first time such a comprehensive plan has been put together. “Believe me, no patient is going to go scouring the literature and assemble 25 different papers and say, ‘Okay, based on this, this is what I need to do to prevent preeclampsia.’ Frankly, no providers are going to do that either,” said Tsigas.

Preventing preeclampsia — which affects about 5-7% of pregnant people worldwide every year — has benefits that stretch beyond pregnancy. Even if a pregnancy ends safely in a healthy birth, people with preeclampsia have more than twice the chance of developing cardiovascular disease later in life than those without it. Doctors can reasonably predict a patient’s risk of preeclampsia based on their medical history and some basic information about them. Someone might be at high risk if they have chronic high blood pressure, are over 40, carrying twins or multiples, have obesity, or are Black. But it’s trickier to consider moderate risk: if it’s somebody’s first child with their current partner, or first child in over 10 years, that’s considered a factor. And still, there are some people like Tsigas who will develop preeclampsia without any easily identifiable risk factors.

Tsigas’ first pregnancy was over 20 years ago, but she still often hears stories that echo her own. Experts know more about preeclampsia than they did back then, but thorough risk evaluations are still not happening across the board.

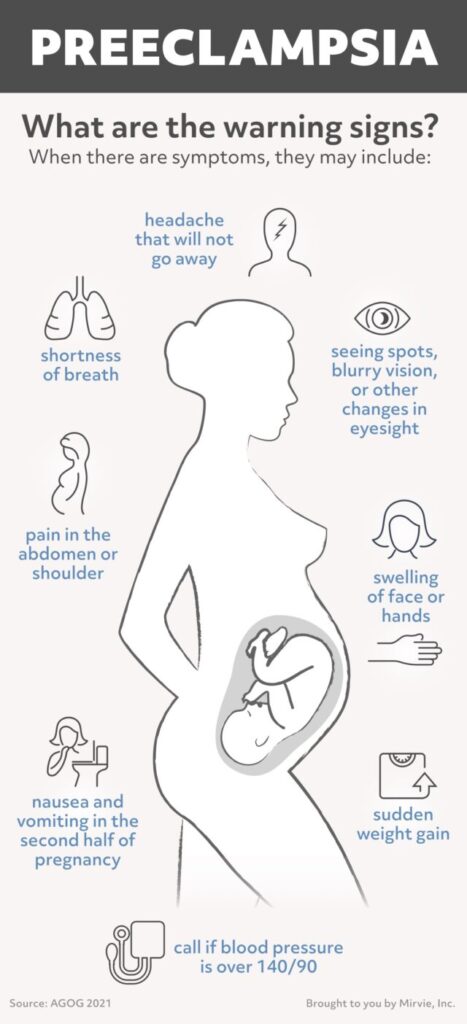

Patients are also more familiar with the condition, but they aren’t as educated on signs and symptoms to look out for. And when they do tell their doctors about concerns, Tsigas says that providers don’t always respond with appropriate urgency.

Experts stressed, in particular, the need for increased blood pressure monitoring during pregnancy. When Tsigas went to the emergency room, she hadn’t had her blood pressure taken in almost a month. That’s still typical for most pregnant people — blood pressure is taken at prenatal appointments that are monthly at the beginning of pregnancy, then every two weeks. Only for the last month of pregnancy are prenatal visits weekly. For moderate and high-risk patients, the plan recommends checking blood pressure much more frequently: every other week until a patient is 20 weeks pregnant, and then weekly after that.

With at-home blood pressure cuffs and broader uptake of telehealth, clinicians and patients can now more easily keep a closer eye on blood pressure between appointments to catch any early signs that intervention may be needed.

“Covid, if nothing else, convinced us that telemedicine can really work,” said James Roberts, a maternal-fetal medicine researcher at the Magee-Womens Research Institute and lead author of the report. In June 2020, the Preeclampsia Foundation began providing at-home blood pressure cuff kits to at-risk women through their providers. To date, they’ve delivered about 25,000 kits.

The report also includes guidance on taking aspirin during pregnancy for those at moderate or high risk of preeclampsia, in line with the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force as well as the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, all of which recommend a dose of 81 mg per day. Patients should start taking aspirin between weeks 12 and 28 of pregnancy, though ideally before week 16, according to the report. The team noted that “reasonable data” show that taking 100 mg per day or higher may also be beneficial, but did not go so far as to officially recommend that higher dose.

Each recommendation is classified as either strong or qualified, and the level of evidence for the recommendation is labeled on a scale from very low to high. Some of the recommendations, particularly increased blood pressure monitoring, are based on the expert opinions of those in the group because there isn’t yet definitive clinical research to support them.

“When there are not good clinical trials, we turn to the people who are doing the work in that space and understand all the biological plausibility and understand the disease,” said Erika Werner, the physician-in-chief of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Tufts Medical Center. Werner was not involved in the report. “The group that put together these recommendations, many of them are the leading researchers in preeclampsia prevention.”

The work was funded by Mirvie, a biotech company working to use RNA sequencing to predict preeclampsia from blood samples before symptoms begin to appear. Researchers are hopeful that technology combined with the care plan could prevent some preterm births, maternal and infant deaths, and other complications due to preeclampsia.

“It’s a complex disorder and it has complex interventions to prevent it. There isn’t one magic pill,” said Alison Cowan, a physician and Mirvie’s head of medical affairs.

Werner hopes that the plan will spur action in creating greater access to resources like at-home blood pressure monitoring tools. The care plan hinges on communication between clinicians and patients, and asks clinicians to evaluate how social determinants of health may affect somebody’s risk of preeclampsia. Because they may be juggling other responsibilities or health concerns, many patients may not be able to reduce their risk by getting a solid seven hours of sleep every night, or exercising regularly. And not all people have access to regular medical care during pregnancy.

Werner believes the plan may be helpful to those patients, too.

“The best care is the most flexible care,” Werner said. “Part of what this care plan does is provide a lot of educational resources and highlights what are the best educational resources, and then empowers patients to use what’s in this tool kit to know their own symptoms and know when to call a clinician.”