The World Health Organization ended the global health emergency for mpox on Thursday, saying that while the virus continues to spread internationally, steady progress has been made in controlling the outbreak.

The decision, announced by WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, came less than a week after the U.N. health agency announced the termination of the global health emergency for Covid-19.

Tedros ended the mpox Public Health Emergency of International Concern, or PHEIC, on the advice of a panel of independent experts, which met Wednesday. He said that although he was declaring the PHEIC over, mpox continues to pose significant challenges that require a long-term, sustainable response.

“I’m pleased to declare mpox is no longer a global health emergency. However, as with Covid-19, that does not mean the work is over,” Tedros said.

Though the PHEIC has ended and growth of new cases is far below its peak from last summer, Tedros stressed that the risk of a resurgence of transmission exists; he urged countries to be on the lookout for such a turn of the tide. Pride month and summer festivals attended by gay and bisexual men who have sex with other men could lead to increased transmission, public health experts have warned.

Still, Nicola Low, co-chair of the mpox emergency committee, said the group determined at this point, there was a need to focus on long-term efforts to end human-to-human transmission of the virus rather than the types of measures needed for an emergency response.

Mpox — formerly known as monkeypox — is a disease caused by a poxvirus that triggers pox-like lesions on the skin and the mucus membranes of people who become infected with it. The virus is a less severe cousin of smallpox, which was declared eradicated in 1980. Smallpox remains the only human pathogen to have been eradicated.

Smallpox could be eradicated because it had no animal reservoir; it only infected humans. Mpox, on the other hand, can infect a range of animals, including many species of small rodents. Though its name would imply that monkeys are its natural reservoir, that is untrue. Monkeys were the first species seen to have been infected with the virus, in 1958. But they are not its natural host.

Mpox lesions can be disseminated or focused in a particular part of the body. Some people develop many lesions, some only a few. Lesions are commonly found on the face as well as palms of the hands and soles of the feet. In this outbreak, where the virus has spread mainly through sexual contact, lesions have often been reported on the penis or around the anus, in the throat or the rectum.

Transmission can occur through respiratory droplets or through contact with infected skin. The virus can also spread through handling of items contaminated with the pus or scabs of lesions, such as bed linens.

It is not known how long the mpox virus has been circulating outside of the countries in Africa where it is endemic, though in recent years, there have been sporadic cases detected in people who were from or who had traveled to one of the endemic countries.

The world first realized international spread was underway last May, when the United Kingdom’s Health Security Agency announced four men had tested positive for the virus. None of the men had traveled outside of the U.K. None had had contact with known mpox cases. All four, though, were men who had sex with men.

It was quickly clear that the virus had spread to multiple parts of the world, fueled, it appeared, by the lifting of Covid-related restrictions on travel and mass gatherings.

In late July, Tedros declared mpox a global health emergency, even though the emergency committee could not reach a consensus that the event merited that designation. On Aug. 2, 2022, Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra declared mpox a public health emergency. That status was allowed to lapse at the end of January.

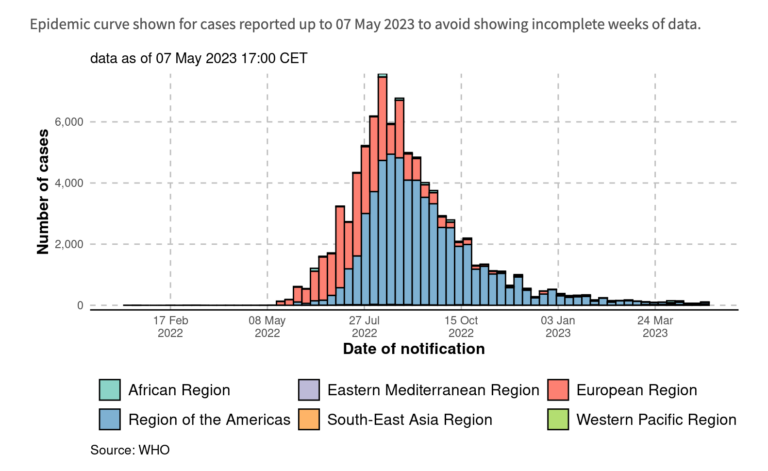

In the intervening months, 111 countries have reported nearly 87,400 confirmed and nearly 1,100 probable cases of mpox, 140 of which have been fatal. Most of the cases have been reported by countries that hadn’t previously seen mpox cases. Most of the infections have been in men who have sex with men.

The United States has reported the highest number of cases, more than 30,000; it has also amassed the highest death toll, 42.

The rise in confirmed cases globally peaked in the week of Aug. 8, 2022, when nearly 7,600 cases were registered. At this point, according to the WHO’s mpox tracker, new cases are being confirmed at a rate of about 123 per week.

The initial response to the outbreak was criticized at the time, with public health officials — worried their messaging could spur homophobia — were hesitant to overtly link spread of the virus to gay and bisexual men. Initial delays in testing and the slow rollout of limited supplies of mpox vaccines and the antiviral drug tecovirimat or TPOXX were also criticized.

But as the summer progressed, at-risk men reported making changes to their sexual lifestyles and vaccination increased.

While new cases are being detected at far lower numbers than they were at the height of the outbreak, one can now contract mpox in many more parts of the world in 2023 than was the case a few years ago. That reality is unlikely to change in the near future.