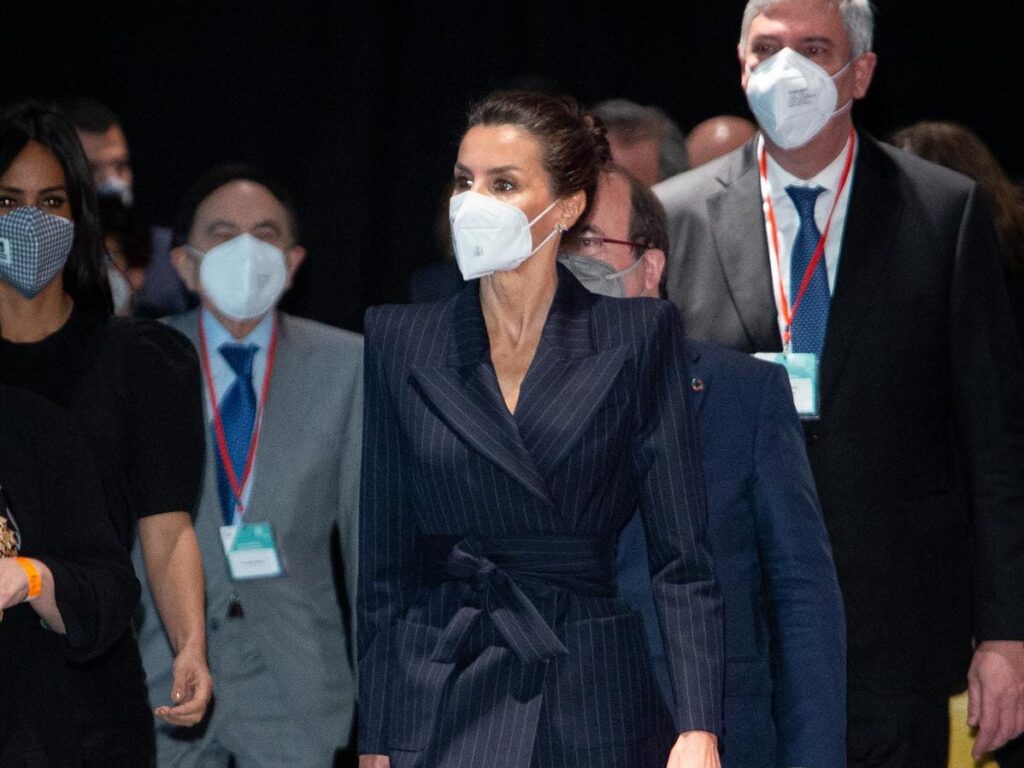

Throughout a fair amount of the Covid-19 pandemic, high profile individuals, such as Queen Letizia … [+]

For years and years, lots of people—such as surgeons, nurses, dentists, dental hygienists, carpenters, construction workers, actors, cosplayers, and Deadpool—regularly wore face masks, in some cases each and every working day. Yet, before the Covid-19 pandemic, did you hear of claims that face masks could somehow cause problems like stillbirths, cognitive problems, long Covid, or something that’s being called MIES (Mask Induced Exhaustion Syndrome)? Yet, now that some politicians and personalities have politicized the heck out of face mask use, suddenly such claims have emerged. And, oh MIES, most recently some folks and anonymous accounts on social media have been trying to push two recent publications, one in a journal called Heliyon and another in a journal called Frontiers in Public Health that have made such claims about face masks. But if you take a closer look and actually read this publication, you’ll find that both are examples of what’s become a popular sport of late: jumping to conclusions.

Indeed, both publications are deeply flawed and also as you’ll see linked together. Neither actually demonstrates that face mask wearing can cause such problems in humans. Instead, both publications employ more hand waving than someone doing jazz hands while trying to stand on a yoga ball. Both publications have some very fruity concerns as well, such as quite a lot of cherry-picking and comparing apples to oranges.

Let’s first look at the publication in Heliyon, which is still a rather new journal that was established in 2015 and has not been focused on public health. Just because Heliyon calls itself an all-science, open access journal doesn’t mean that you should automatically say, “Hell, yeah,” to anything published there. The lead author for this publication is someone named Kai Kisielinski, described as “Independent Researcher, Surgeon,” which doesn’t mean much. Heck anyone can call themselves that. It’s unlikely that anyone would call themselves a “Highly Dependent Researcher.” Remember the name Kisielinski as it will come up again soon.

OK, moving on to the actual publication itself, which is self-labelled as a “scoping review.” Now, a scoping review does not mean that you review something while gargling mouthwash. But it is not yet completely clear what a scoping review is supposed to be. It’s not really a thorough, comprehensive review of what studies have been done around a particular topic. In fact, a scoping review of scoping reviews published in Research Synthesis Methods in 2014 indicated that “The scoping review has become an increasingly popular approach for synthesizing research evidence. It is a relatively new approach for which a universal study definition or definitive procedure has not been established.” This raises the risk that a scoping review can end up cherry-picking whatever studies may support a particular point-of-view.

The Heliyon scoping review listed some studies that showed that wearing a face mask for more than five minutes could potentially raise the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) that you are breathing by a few percentage points. The argument posed by the authors of this scoping review is that when wearing a face mask, you are breathing back in more air that you’ve just breathed out rather than fresh air. The authors then cite some studies in non-human animals such rats and guinea pigs that have shown that chronic exposure to CO2 was associated with an increased risk of stillbirths and problems in offspring like irreversible neuron damage and “reduced spatial learning caused by brainstem neuron apoptosis and reduced circulating levels of the insulin-like growth factor-1.” The authors also pointed to studies of rat testicles when they claimed that “there is also data indicating testicular toxicity in adolescents at CO2 inhalation concentrations above 0.5%.”

Throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, some people have also politicized the heck out of face mask use. … [+]

You’ve got to be careful about extrapolating what’s been found in studies of other animals to what may happen in you. That could be like comparing apples to oranges or Tim Apple to someone who uses orange spray tan. They are not necessarily the same.

And what happens in rodents may not happen in humans. Your body and rodent bodies are not identical. For example, speaking of spherical objects, presumably rat testicles are not the same as your testicles. If you don’t believe this to be the case, try posting on your dating profile that you have rat testicles and see what reaction that gets you. Plus, chronically exposing rodents to higher levels of CO2 is not necessarily the same as getting them to wear face masks. Of course, getting a rodent to wear a surgical mask or an N95 respiratory could be challenging. That rodent may not wear it properly and could yell things like, “Freedom. They’ll never take our freedom!” Nevertheless, it’s quite a jump to say that wearing face masks may increase the CO2 levels that humans are breathing in by a few percentage points, say that chronic CO2 exposure under lab conditions has been associated with problems in rodents, and then claim that face mask wearing may cause such problems in humans.

Yet, the authors did insist on making such a big jump. Look at the conclusions that they wrote without really providing adequate supporting evidence: “There is a possible negative impact risk by imposing extended mask mandates especially for vulnerable subgroups. Circumstantial evidence exists that extended mask use may be related to current observations of stillbirths and to reduced verbal motor and overall cognitive performance in children born during the pandemic. A need exists to reconsider mask mandates.”

At the same time, the authors did not fully acknowledge the limitations of what they had put together. And they did not present the abundance of scientific evidence that has supported the use of face masks to prevent Covid-19 transmission. They also failed to mention the fact that again people like surgeons, nurses, dentists, dental hygienists, and others have been wearing face masks for years. Are Kisielinski and his co-authors now trying to say that those professions should stop using face masks? By the way, isn’t Kisielinski listed as a surgeon? Wonder if he’s worn face masks in the operating room all these years.

Speaking of Kisielinski. Guess who was the first author for the Frontiers in Public Health publication. Yes, you got it: Kisielinski. In fact, many of the authors (Susanne Wagner, Oliver Hirsch, Bernd Klosterhalfen, and Andreas Prescherare) were on both publications. With Kisielinski as the first author and Prescherare as the last author on both publications, essentially the same group of folks produced both publications.

Therefore, it’s not surprising that the Frontiers in Public Health publication had some of the same flaws that the Heliyon publication did. The Frontiers in Public Health publication described what the authors called a systematic review of any study that may have shown “adverse effects of face masks on metabolic, physiological, physical, psychological, and individualized parameters.” This meant that they searched the literature for controlled intervention studies and observational studies that measured thing such as “peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), carbon dioxide levels in blood, temperature, humidity, heart rate, respiratory rate, tidal volume and minute ventilation, blood pressure, exertion, dyspnea, discomfort, headache, skin changes, itching, psychological stress, and symptoms during the use of face masks.” Of course, one immediate issue is that such an approach throws apples and oranges together. Different studies looked at different things and circumstances. For example, in some cases, these measurements were taken while people were exercising strenuously, which is not the same as wearing a face mask in the grocery store, assuming that you don’t regularly do burpees in the produce section or pant heavily when you’re in front of the melons.

Not surprisingly, the collected studies did show some differences in certain measurements when taken with and without face masks. After all, things aren’t completely the same between wearing a face mask versus not wearing one just like things aren’t completely the same between wearing underwear and not wearing underwear. If you are not wearing underwear or anything else, your heart rate, respiratory rate, and other things are likely to go up, or down depending on what you are talking about.

But the big question is not whether any measurements changed, but how much they changed and whether such changes would actually make a difference to your health. Eric Burnett, MD, a hospitalist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, posted a Twitter thread, that—how shall we say it—tore this paper and Jeffrey A. Tucker, the founder of the Brownstone Institute who has been pushing this paper, a new one:

From Twitter

In the thread, Burnett asked Tucker, “If statistically significant differences = clinically significant differences,” after summarizing what the Frontiers in Public Health publication did:

From Twitter

Burnett then pointed out the relatively small differences in blood oxygen and CO2 levels found between those wearing masks and those not:

Burnett also emphasized that the authors of the Frontiers in Public Health publication heavily weighted a study that had focused on 97 patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is known to already cause severe breathing problems:

Isn’t studying face mask use among those with COPD sort of like studying the use of peanut brittle among those with peanut allergies? Burnett went on to highlight how the authors also included a very flawed study in their analysis:

Meanwhile, Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, an epidemiologist who calls himself a “Health Nerd”, described in a blog on Medium the Frontiers in Public Health publication as being “absolutely filled with basic errors.” Meyerowitz-Katz showed how the authors had on multiple occasions pulled the wrong numbers from the studies that they reviewed. For example, Meyerowitz-Katz wrote, “For one trial, Goh 2019, the authors said that the value for blood C02 was 27.1 in the no mask group and 32 for those wearing masks — actually, the first number should’ve been 28.2. The authors accidentally took the pre-exercise number from the surgical mask group, rather than the number from the control group who weren’t wearing masks.”

All in all, the errors, the comparing apples to oranges, the inclusion of a flawed study, the small degrees of changes found, and leaps to conclusions meant that the Frontiers in Public Health publication just did provide enough evidence to support the claims that it made. The authors claimed that face mask wearing can lead to something that they are calling MIES and asserted in an unfounded manner that MIRES may resemble long Covid.

Just because a publication somehow made it through the editorial process at some journal doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s completely legit and mistake and B.S. free. And in this case, B.S. doesn’t stand for Bachelors of Science. You can’t mask the fact that many other studies have shown the benefits of face masks in preventing the transmission of airborne viruses like the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). You also can’t mask the fact that many people in different professions have been regularly wearing face masks for many, many years long before the Covid-19 pandemic.