Joseph Maroon, a neurosurgeon, began working for the Pittsburgh Steelers as a consulting doctor starting in 1977 and over 46 years has examined and treated stars from the notoriously hard-nosed dynasty, including the Hall of Famers Terry Bradshaw, Mean Joe Greene and Lynn Swann.

Many of them, he said, worry about the health of their brains because they played when concussions were viewed as “dings,” full-contact practices were common and the most violent hits were still permitted.

“Certainly, everyone who has participated at that level has some concern,” Maroon said last week in his office at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Presbyterian Hospital. “But we haven’t seen the epidemic that one might anticipate from playing in that era with less protective helmets, less rules and harder fields. There’s just so many unknowns.”

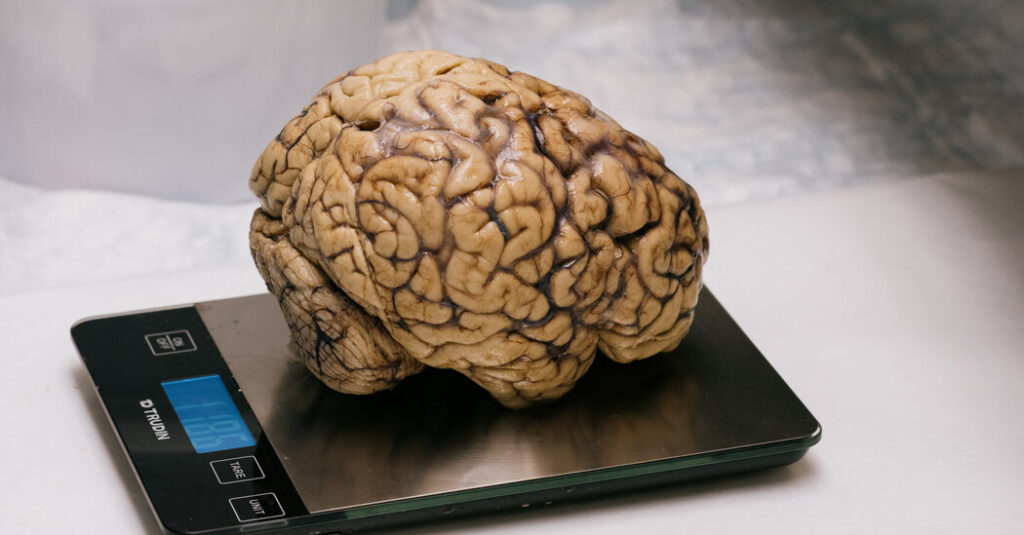

A growing number of scientific studies done over the past 15 years have found links between repeated head trauma and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a degenerative brain disease. Many of those have come via the C.T.E. Center at Boston University, which has examined the brains of hundreds of former N.F.L. players and other athletes and military personnel.

But Maroon, who in the past has called the rates of C.T.E. in football players a “rare” phenomenon and “over-exaggerated,” felt there needed to be more research on why some athletes have few or none of the symptoms tied to C.T.E., including memory loss, impulse control issues and depression, while others are overwhelmed by them.

So five years ago, Maroon and the Steelers’ owner, Art Rooney II, approached doctors at the University of Pittsburgh’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center to discuss starting a sports-focused brain bank that studies the roles that age, genetics, substance abuse, the number of head hits and other factors play in the development of C.T.E.

The result is the National Sports Brain Bank at the University of Pittsburgh, which will formally open on Thursday. After being delayed several years by the Covid-19 pandemic, the center has accepted pledges of brains from athletes including the former Steelers running backs Jerome Bettis and Merril Hoge.

C.T.E. can be diagnosed only after death, and doctors are still years away from developing a test to detect the disease in the living, so posthumous donations to brain banks are still the primary method of advancing the research.

The center will also begin recruiting volunteers — athletes from all levels of sports, as well as nonathletes to serve as a control group — to provide their health histories and be monitored in the coming years. That information will be compared to the conditions of their brains after they die to determine which, if any, factors played a role in their having or not having C.T.E.

“We don’t know where the threshold is for C.T.E.,” said Julia Kofler, the director of the neuropathology department at the University of Pittsburgh, who will oversee the sports brain bank. “You certainly see cases that had very minimal pathology that had symptoms, and that’s the question. I think we really need to have as many cases as we can to answer these epidemiological questions.”

The National Sports Brain Bank will rely on the infrastructure at the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, which already has more than 2,000 brains, though most are not from athletes. The Sports Brain Bank will use seed funding from the Chuck Noll Foundation, the Pittsburgh Foundation and the Richard King Mellon Foundation to find volunteers for the long-term study and people willing to pledge their brains.

Maroon, Kofler and others in Pittsburgh acknowledged the work of doctors at Boston University, who have been the undisputed leaders in C.T.E. research. Researchers there have more 1,350 brains not just from football players, but also from athletes who played hockey, rugby, soccer and other sports, as well as members of the military. So far, about 700 of those brains have been found to have C.T.E.

But Maroon said that some research produced by the Boston group was biased, because families had typically donated the brains of relatives who exhibited symptoms consistent with C.T.E. when they were alive. When asked to provide details of their loved ones’ head traumas, those families’ memories of the former players’ concussion histories might be imprecise.

The long-term study undertaken by researchers at Pittsburgh should “reduce, eliminate, obviate that kind of bias,” Maroon said.

Ann McKee, the neuropathologist who leads the C.T.E. Center at Boston University, said her group had for many years acknowledged the selection bias among families. She also said doctors at Boston University were already undertaking several longitudinal studies.

“We are doing all of this,” McKee said, adding that “it’s always great to have another group involved, and it’ll accelerate the research and accelerate scientific discoveries, especially concerning treatment. So that’s fantastic.”

Unlike Boston University, the National Sports Brain Bank is not shying away from ties to the N.F.L. The Chuck Noll Foundation for Brain Research, named for the former Steelers head coach who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease before his death in 2014, has provided seed money to the bank. The foundation was started in 2016 partly with a donation from the Steelers’ charitable arm and has provided more than $2.5 million in research grants to explore the diagnosis and treatment of brain injuries, primarily those that occur in sports.

“It was important for the Steelers that we get behind this,” Rooney said in a phone interview. “Obviously, we’re in the early stages of this, but we’re hopeful that it gets the kind of attention that it’s going to need to really be successful.”

Hoge, the former Steelers running back who has agreed to donate his brain, said he had chosen the National Sports Brain Bank because the University of Pittsburgh and other institutions in the city had been centers of innovation in brain health, including the development of helmet technology. He also noted that Noll, his former coach, had pushed for the development of a test to evaluate a player’s cognitive abilities that could be used as a baseline to identify concussions. It was a forerunner to the Immediate Post-Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Test (IMPACT) that has been used globally.

Hoge, who in 2018 co-wrote the book “Brainwashed: The Bad Science Behind C.T.E. and the Plot to Destroy Football,” added that he believed in the integrity of the research at the Pittsburgh brain bank.

“There’s so much misunderstanding and fear,” Hoge said. “Helping them find that right information and giving them other information and resources to help them with the thought process, I think, is very important.”

Gil Rabinovici, the director of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco, said that “this type of research is best conducted when the funders and investigators are free of any potential conflicts,” referring to the Pittsburgh group’s N.F.L. links.

He added that the researchers in Boston had done an “excellent job” in describing the pathology of C.T.E., “but in science, you look for independent replication with different groups studying the same scientific questions using different methods, and hopefully reaching similar conclusions.”