In Phoenix, where daytime temperatures are topping 110 degrees Fahrenheit for the third straight week, emergency room doctors think of extreme heat as the public health emergency it has proved itself to be: In 2022, Arizona’s Maricopa County reported a 25% increase in heat-related mortality from the previous year.

“Heat is just something we know we need to be really worried about,” said Geoff Comp, an emergency medicine physician at Valleywise Health Medical Center. Protocols developed by Comp, who is also associate program director of the Creighton School of Medicine/Valleywise emergency medicine residency, include treating heat stroke victims with the latest standard of care: immersive cooling in a body bag filled with ice and zipped to about shoulder level.

The ED has two big freezers of ice at the ready, and can get more from the food service department.

Body bags are the ideal way to treat heat stroke victims because they are waterproof, cool a person about twice as quickly as traditional methods, and compactly contain both the person being cooled and the melting ice, Comp said, adding, “If you have a better name, ‘cause, you know, that makes people uncomfortable,” given their association with cadavers. The bags allow room for IV tubing, temperature probes, and even intubation if necessary, and they are capacious enough to allow doctors to perform some procedures: Doctors at Valleywise once successfully used a defibrillator on one patient who was suffering ventricular arrhythmia while cooling down in a body bag.

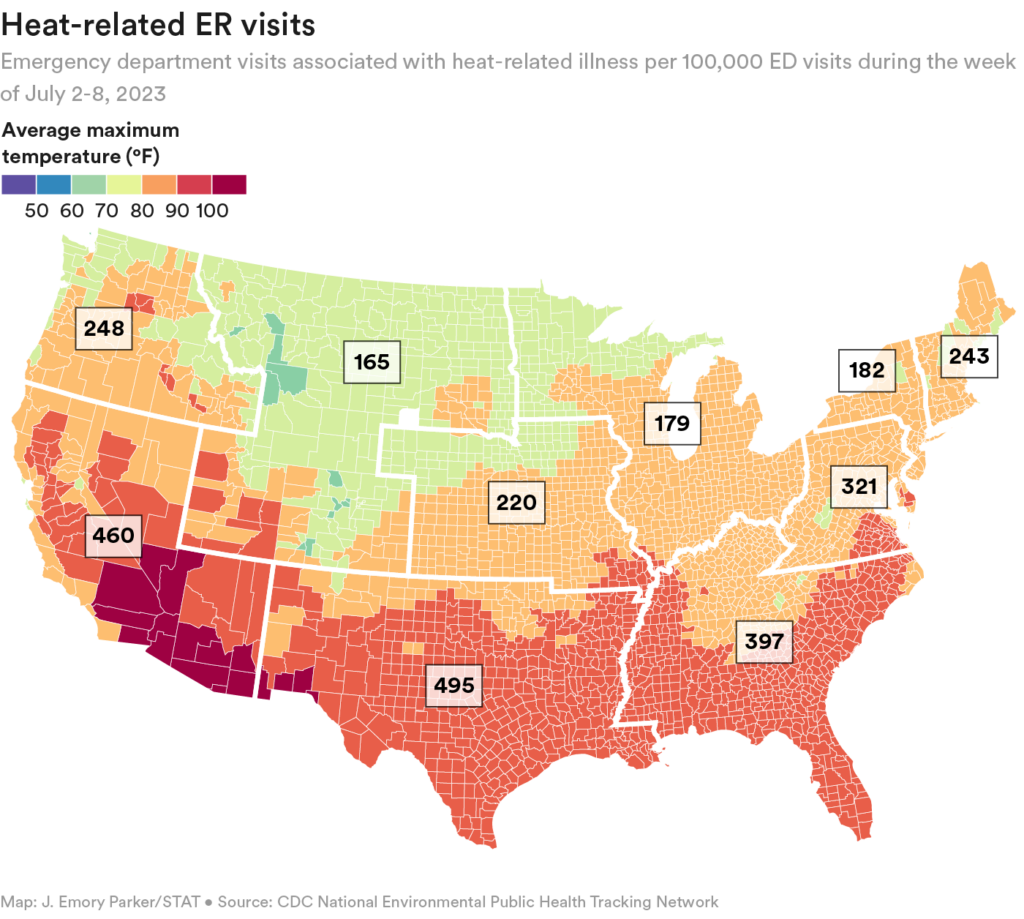

Finding a lifesaving purpose for body bags is but one way in which clinicians are thinking creatively about dealing with the growing threats from extreme heat. With each decade since the 1960s, heat waves across 50 U.S. cities have, on average, become more frequent, more intense, and lasted longer. Just as global warming and climate change have resulted in more extreme heat around the world, mortality attributable to heat-related illness has climbed in the U.S., not only in traditionally vulnerable regions such as Arizona and Texas, but also in historically temperate places like the Pacific Northwest, where 2021’s heat dome resulted in 650 deaths in the U.S. and the Canadian province of British Columbia. Experts believe extreme heat is also linked to higher all-cause mortality.

Emergency departments in places like Arizona and Texas have long experience in dealing with heat waves, and are generally well-equipped to handle the few heat stroke victims that may arrive each day during sporadic heat waves. In Phoenix, Comp said he and his colleagues have noticed that some people may already be adapting, staying home in the intense heat or going to the ER earlier, before they suffer heat stroke and require immersion in body bags: The ER has not used quite as many as they had by this time last year.

But extreme heat, especially in locales not accustomed to them, has the potential to become a “mass casualty event,” said Christopher Tedeschi, director of emergency preparedness at NYP-CUMC Emergency Medicine in New York. The greatest pressure on emergency care comes when temperatures stay high for several days, and brownouts or power outages occur.

“There’s a domino effect,” Tedeschi said. “When it gets that hot, more people present with cardiovascular events, more people present with respiratory problems, more people present with strokes. … Our emergency departments are dangerously overcrowded and that overcrowding is our biggest threat when dealing with a disaster. Hands down.” After Hurricane Sandy took out power in New York City for days in 2012, he added, “we had people coming in the door saying, ‘I need dialysis,’” because the centers they usually went to were dark.

The list of people who are vulnerable to heat-related illness is long: infants and young children; elderly people; people with chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, COPD, and kidney disease; pregnant people; people with dementia; people with mental illness; and people on certain classes of medications that increase heat sensitivity. Yet that vulnerability is mitigated by income and place of residence — the ability to stay out of the heat and cool down with the flick of a switch for air conditioning.

The people who suffer disproportionately from heat-related illnesses are people of color, people who have relatively low incomes, people who can’t afford AC (or the electric bill that comes with it), and people who have no choice but to work — and even live — outside during oppressive heat.

“Urban heat islands” in large cities, the product of decades of redlining, are “asphalt-rich and tree canopy-poor” danger zones, with much higher ambient temperatures than nearby tree-lined areas. In Portland, Ore., in June 2021, canopied areas of the city recorded a temperature of 116 F, while the mercury in heat islands in the city hit 130 F, and that was “absolutely catastrophic,” said Leah Werner, a family medicine doctor and researcher at Oregon Health & Science University.

Asphalt’s temperature climbs still higher. In cities like Phoenix, it can reach 180 F during heat waves, creating a risk in addition to that of heat stroke: serious burns from only brief contact such as falls. The Arizona Burn Center recently reported that it had 85 admissions from heat-related burn injuries last summer. Seven of those patients died from their injuries. Some of the individuals came to the hospital hyperthermic, with body temperatures of over 108 degrees, and 26% were unsheltered.

Heat stroke is the greatest health risk from extreme heat, with a mortality rate of anywhere from 10% to 65%, depending on factors such as length of exposure to heat, the level of internal body temperature when emergency care begins, and a person’s underlying health. There are two types of heat stroke — exertional, with an onset of a few hours (think of a student athlete at practice, or an agricultural worker), and non-exertional, or classic heatstroke, which develops over several days (think of an elderly person marooned in a stifling apartment with no AC). Both are characterized by an internal body temperature of 104 F (40 C) or higher and an altered mental state. Those who survive heat stroke are at increased risk of mortality from other causes, because of the potential for permanent acute damage to the heart, kidneys, and liver.

And, short of heat stroke, people can suffer heat exhaustion, characterized by fever, dizziness, and nausea, all of which stem from the body’s inability to cool itself. The prognosis for heat exhaustion is good with hydration and cooling, but if left untreated heat exhaustion can rapidly progress to heat stroke.

Planning for prevention

The huge risks associated with heat-related illness mean that prevention is paramount. The onus is on primary care doctors to educate and prepare people — especially those who are most at risk — so that they can take measures to avoid the heat, and thereby reduce the pressure on emergency departments.

A new pilot project for community health centers and free clinics serving underinsured and uninsured patients sets out to do just that. Since its initial rollout a few months ago, information from the toolkit Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics has been downloaded more than 10,000 times, and 54 clinics have participated in training sessions on using the resources. The project, which has resources on hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires, as well as heat, is a collaboration between Americares, a global health-focused relief and development organization, and the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment. (The biotech Biogen provided donor support.)

Clinic administrators and providers receive special weather alerts and can refer to a detailed and evidence-based array of resources, in both English and Spanish, to help them deal with heat emergencies. The provider info sheet for protecting pregnant patients from heat-related illness, for example, notes that high temperatures can lead to numerous poor outcomes, such as low birth weight and stillbirths, and that “heat stress may trigger uterine contractions or lead to placental inflammation, either of which may promote preterm labor.” The mental health info sheet for providers states that, “Individuals with psychotic conditions may be at particularly high risk from heat exposure owing to impairment in judgment,” and warns that some psychotropic medications may impair thermoregulation.

Administrators at clinics can find guidance for setting up a heat alert plan and checklist, and for facility preparedness ahead of a heat wave. And info sheets can be distributed to clinic patients. The toolkit’s heat guidance is coupled with alerts from Climate Central, sent two days ahead of expected high temperatures. The customized advance warnings make it easy for providers to warn patients to prepare themselves, said Gaurab Basu, a Harvard School of Public Health professor who is using the toolkit and alerts in his primary care practice at Cambridge Health Alliance. “I agree with the sentiment that in medicine our interventions are too reactionary,” said Basu. “We need to be more proactive in communicating public health risks.”

At the San José Clinic in Houston, practice and quality director Erlee Rodriguez received the first heat alerts from the system in late June during an early summer heat wave, and immediately relayed the information to practice providers and readied materials for providers and patients. The charity clinic, which last year served 3,619 patients via 30,020 visits, relies on a network of volunteer providers. While the clinic’s patients and providers alike are generally familiar with extreme weather and its consequences, the “neatness about this program is we have been able to incorporate the virtual element and also have the alert system that gives us accurate data,” said Rodriguez. Providers and staff have been trained on information in the toolkit, and patients — 80% of whom are Spanish-speaking — are getting the information, either online or printed for them, in Spanish and English. Even the front desk staff know to look for tell-tale signs of heat exhaustion when patients arrive for appointments, he said.

Rodriguez added that providers are using the toolkit’s resources — one told him the detailed information about heat-related exacerbations of certain chronic diseases exceeded what she had learned in medical school. And doctors at the clinic are working with their patients prior to a heat event to develop a “heat action plan.” Appropriate guidance, according to the toolkit, should be based on assessment “of the severity of their disease, co-morbidities, occupation (especially if outdoors), access to air conditioning at home, and excess heat exposure from an urban heat island or the home environment.”

One critical part of any such plan: getting air conditioners and air purifiers to those who don’t have them in their homes, and directing those residents, as well as unhoused people, to cooling centers if they can’t otherwise secure a cool spot. This summer, New York City offered a “cooling assistance benefit” of up to $800 for a window or portable air conditioner or fan to eligible residents. And in the wake of the 2021 heat dome, “Cooling Portland” distributes and installs portable heat pump/cooling units for low-income residents. Numerous localities offer low-income home energy assistance programs, supported by federal funds, to help reduce energy bills.

Ideally, the day will come when a provider can simply write a “prescription” for an air conditioner that can be readily filled, said OHSU’s Werner. She and colleague Jennifer DeVoe are advocating a “precision ecologic medicine” approach that would not only incorporate social and economic risks and other “community vital signs” in a patient’s electronic medical record, but would also enumerate climate-related health risks — if their residence is an urban heat island, for instance, or their occupation is one that keeps them outdoors.

In their frontline clinics, clinicians are doing a lot of that assessment informally right now. But Werner argues that community vital signs, including climate risks, need to be measured and imbedded in the medical record in such a way that with a mere push of the button, a doula can be lined up during a heat wave, for instance, to help a pregnant Black woman who lives on a heat island. In Portland, said Werner, many family care clinics are “built to do this already; we just have to add a few more tools to our toolbelt and continue to refine. We’ve got to build a flow where this is seamless,” said Werner.

As summer segues into fall, the greater climate threat in the U.S. is likely to be posed by storms and hurricanes and the potential flooding that can follow. Climate threats have been with us since the dawn of time, noted emergency physician Caleb Dresser, who’s leading Harvard’s effort in the Americares-Harvard climate resilience project. But as their frequency and intensity grow, a body of health research has also grown that demonstrates the risk and potential for harm from extreme climate events. Some clinicians have a familiarity with the health consequences, but “haven’t made it a systematic part of their practice,” said Dresser. Others, up until recently, may not have received training in climate health risks. But with climate change, such knowledge is becoming critical. All clinicians, he said, need easier ways to translate information into meaningful action — and the care that the most vulnerable of their patients need.

This story is part of ongoing coverage of climate change and health, supported by a grant from The Commonwealth Fund.