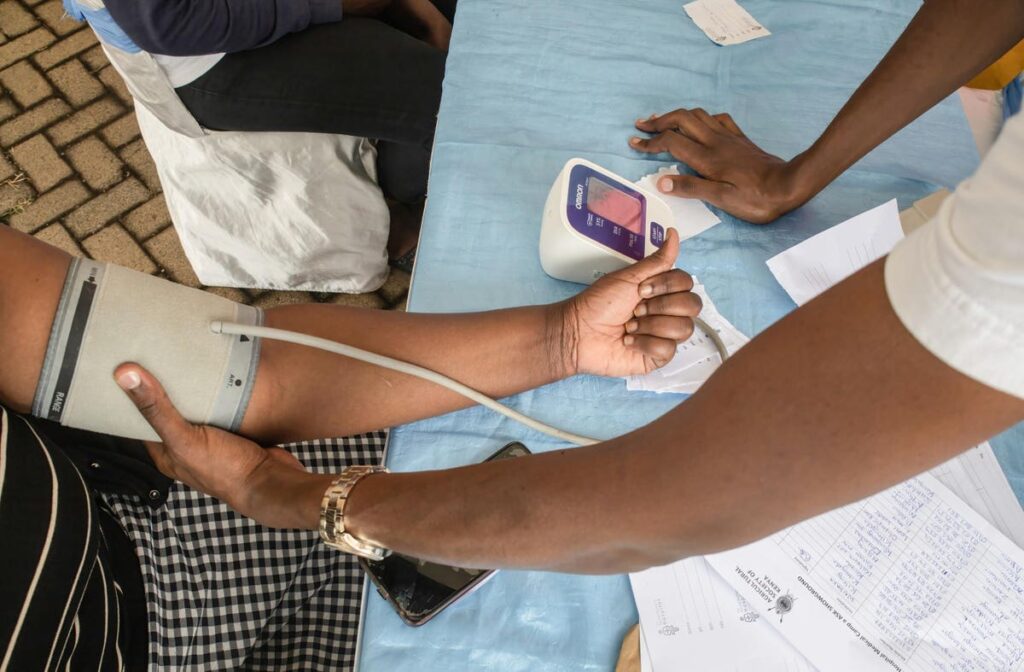

A nurse measures a patient’s blood pressure during a free breast cancer exam in Nairobi. (Photo by … [+]

You almost certainly know someone living with hypertension (high blood pressure). That person might be you yourself.

As noted in a new World Health Organization (WHO) stock-take report, its first on hypertension globally, fully one in three adults has hypertension. The number of people with the condition has doubled in the past 30 years, to reach 1.3 billion.

It’s so common that it may be taken for granted, or treated as fairly benign. Yet it’s the leading risk factor for mortality, often implicated in heart attacks and strokes.

The good news is that treating hypertension isn’t rocket science. Nor will it break the bank.

“Treatment is low-cost, safe, effective, and can be done by nurses, pharmacists, and community health workers,” stressed Tom Frieden, the head of the health nonprofit Resolve to Save Lives, speaking at a press briefing on September 18.

Dietary change is one useful tool. Lowering sodium and raising potassium is a proven formula for lowering blood pressure. This involves cutting back on highly processed foods and adding in more fiber, fruit, and vegetables. Using salt substitutes enriched with potassium has been proven to be effective (though the WHO doesn’t make any recommendations about potassium supplements).

“Too much sodium is a major risk factor and contribute to more deaths than any other dietary risk factor, but barely 6% of the world’s countries have effective measures in place to tackle excess sodium consumption,” explained Frieden.

Yet there is an established set of policies that have helped to bring down sodium consumption, Frieden commented: “Things like salt targets for packaged foods…healthy public food procurement and service policies, and front-of-pack warnings – as pioneered by countries in South America – all work.”

However, as the WHO report cautions, there are limits to the power of eating habits alone, even when combined with more exercise. Almost everybody diagnosed with hypertension will need the help of medications to control the condition. Lifestyle changes can complement medicines, but won’t replace them.

Yet medicine access isn’t always a given. One problem is highly inconsistent pricing of hypertension drugs, even though safe and effective medicines can be manufactured very cheaply. In Kenya, for instance, the markup on amlodipine can be over 340%.

“There is a huge access problem,” noted Bente Mikkelsen, the director of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) for the WHO, also speaking at the press briefing. “If you look at the prices of medicines it is…almost catastrophic. These are very cheap molecules.”

Lack of access to medicines is one reason for disparities in treatment. Frieden said, “For more than half a century, treatment of high blood pressure has been standard of care in higher-income countries. It’s way past time for it to become standard of care for every person in the world.”

He continued, “Ensuring regular supply of medicines and high-quality blood pressure monitors as little as $5 per patient per year. However, this has been more than many countries have been able to spend. And we’ve seen huge variability in the cost of medications among countries.”

“This is really value for money,” Mikkelsen agreed. “It is an immoral fact that we have off-patent medicines that are not still available.”

Frieden emphasized that “unless medicines are free, the poorest and most vulnerable patients may be forced to choose between food and medications.”

Free care has transformed the scale of hypertension treatment in Bangladesh, for instance. There, Frieden explained, “in partnership with the Bangladesh National Health Foundation, the government has increased the number of patients treated by 20-fold while at the same time more than doubling the control rate.”

While reducing sodium intake, air pollution, and lead exposure have all played a role, “One key to success is that clinic visits and medicines are free and accessible for patients.”

More broadly, Frieden reported, “we’re seeing treatment programs like those in Bangladesh, the Philippines, India, scale up in a very encouraging way. It shows it’s possible with government leadership and government ownership and a focus on effective programs.”

Governments need to ramp up spending on diagnosing and treating hypertension, including the basics like actually assessing blood pressure in primary healthcare clinics. “There is no excuse for any country not to measure blood pressure,” emphasized Mikkelsen.

But the global development community has a crucial role as well. It’s been ducking this role, with a traditional focus on infectious diseases that has led to blind spots about noncommunicable diseases.

“In some countries we only have primary healthcare facilities that have been set up for HIV or malaria,” Mikkelsen said. Integrating something as basic as blood pressure measurements into those facilities, without displacing the important work they’re already doing, would go some way to reducing deaths.

Frieden called it “unacceptable that the single leading cause of death in the world was less than 1% of global health development funding.”

Positively, “In the next 25 years, improved blood pressure control could prevent more than 70 million deaths and approximately 120 million strokes and 80 million heart attacks,” according to Frieden. But it requires the will and the funding.

Ultimately, Frieden said, “This is a pivotal moment. It’s a turning point.”