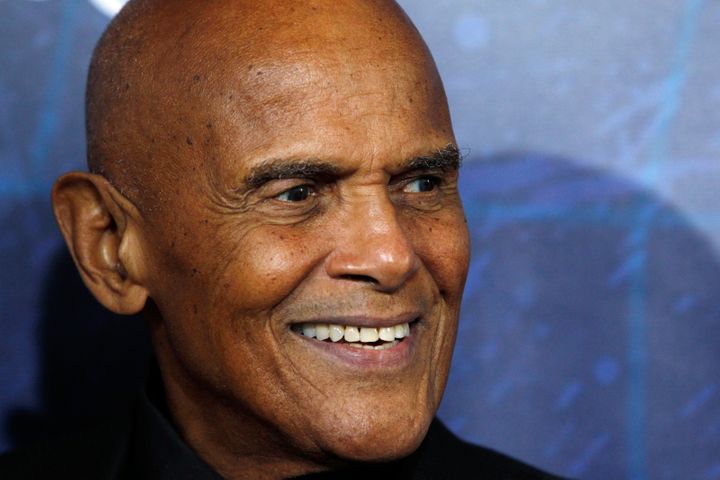

Harry Belafonte, a beloved singer, actor and activist credited with introducing the United States to Caribbean music and bankrolling the civil rights movement, died on Tuesday at 96, The New York Times reported, citing his spokesperson.

Belafonte first achieved fame in the 1950s with film and musical theater roles that broke new ground for Black Americans in the entertainment industry.

His career truly took off, however, when he recorded wildly popular renditions of Caribbean folk and calypso songs, including, most famously, “Day-O (Banana Boat Song).” The King of Calypso, as he became known, used the considerable wealth and publicity he earned to advance civil rights and other progressive causes right until his death.

The election of former President Donald Trump in 2016 reignited Belafonte’s passion for social justice anew. He served as a co-chair of the national Women’s March protests against the new president in January 2017.

“I’m playing a role that I feel equipped and I feel knowledgeable about,” Belafonte said in an interview at the time. “I’m going to be 90 years old in a couple of weeks, and I think that to be of mind and capacity to be able to still contribute to helping to make our union a better place, to help our country become a better place, is a joyous task.”

Jessica Rinaldi / Reuters

Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. was born to Jamaican immigrants on March 1, 1927, in Manhattan. His mother, who was not authorized to live in the U.S. until later in her life, eventually changed their family name to Belafonte to avoid detection by immigration authorities.

Belafonte, who spent part of his childhood in Jamaica, returned to Manhattan for high school. He dropped out, however, at age 17 to join the U.S. Navy during World War II. Belafonte’s experiences with racism in the military made a lasting impression on him.

Describing his decision not to reenlist, Belafonte wrote in his 2011 memoir, “My Song,” “I’d had enough of military service: not just the numbing routine and the mortal risks with munitions but the all-too-frequent incidents of prejudice that kept me in an almost constant state of simmering rage.”

As a young adult working as a janitor following his military service, Belafonte stumbled upon his love for acting when a tenant in the building where he worked provided him a ticket to attend a play at the American Negro Theater in Harlem. Enamored of what he saw, Belafonte volunteered there and eventually landed his first acting roles at the theater. It was also where he met his friend and fellow Carribbean-American trailblazer, Sidney Poitier, who went on to become an Oscar-winning actor.

With help from the GI Bill, Belafonte took acting classes at the Dramatic Workshop of New York’s New School, where he studied alongside Hollywood legends Marlon Brando, Walter Matthau and Tony Curtis. A singing role in a college play there led to nightclub appearances and a recording contract.

Belafonte’s fame rose steadily in the mid-1950s. Following his big-screen debut in “Bright Road” (1953), Belafonte starred in “Carmen Jones” (1954), a modern-day gloss on the tragic opera “Carmen” that was a critical and commercial success.

Although both Belafonte and his co-star, Dorothy Dandridge, were Black, his performance was so strong it convinced a censor in the Jim Crow South to green-light the film’s screening.

“I never saw a better tragedian than” Belafonte, an official on a Tennessee county censorship board said at the time.

20th Century Fox/Getty Images

Debuting on Broadway in 1953, Belafonte won his first and only Tony Award for a supporting role in the musical revue “Almanac,” where he sang the folk song “Mark Twain.”

In early performances like those, Belafonte drew acclaim for his unadorned yet passionate singing style.

“He cares about what he is doing, and his furious conviction is like a jolt in a show dedicated largely to light entertainment,” a New York Times critic wrote of Belafonte’s Tony-winning role.

Belafonte’s musical career took off shortly thereafter, becoming what he was known for.

“Calypso,” Belafonte’s third studio album, made him a breakout star in 1956. With hits like “Day-O” and “Jamaica Farewell,” it was the first album from any artist to sell more than a million records, and it topped the Billboard charts for 31 consecutive weeks.

In the wake of the record’s monumental success, Belafonte packed concert halls and stadiums, making calypso trendy with a mainstream American audience.

“Handsome young Harry Belafonte, folk singer, motion-picture star and night club entertainer, drew the largest crowd in the thirty-nine-year history of the Lewisohn Stadium concerts last night,” raved a Times review of his June 1956 concert in Manhattan. “Clad in black slacks and scarlet open-neck shirt, Mr. Belafonte quivered with emotion in the spotlight as he sang ‘Water Boy.’ And more than 25,000 fans quivered with him.”

CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

In the 1960s, Belafonte continued to perform live and recorded several more successful albums, including two that won Grammys: 1960’s “Swing Dat Hammer” and his 1965 collaboration with South African artist Miriam Makeba, “An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba.” His 1961 recording of “Jump In the Line,” from the album “Jump Up Calypso,” is another enduring favorite.

That same decade, Belafonte became the first Black television producer, presiding over numerous musical productions.

As Black Americans’ fight for basic freedoms heated up in the ’50s, Belafonte struck up a close friendship with Martin Luther King Jr., becoming a leading voice of the civil rights movement and one of its biggest benefactors.

He spoke at the March on Washington in 1963, and financed the efforts of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a civil rights outfit led by then-activist John Lewis. In 1964, Belafonte, together with Poitier, traveled to Mississippi carrying a doctor’s bag stuffed with $70,000 to help fund voter registration as part of the Freedom Summer campaign.

But it was Belafonte’s platform as a beloved celebrity, rather than his wallet, that arguably proved to be his most potent contribution in the fight for civil rights. He enlisted stars like Marlon Brando, Paul Newman and Tony Curtis to join him in the final, successful voting rights march in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery in March 1965, just weeks after state police brutally beat civil rights leaders in the incident that became known as Bloody Sunday.

As a guest host of “The Tonight Show” for a week in February 1968, Belafonte cast a national spotlight on some of the leading artists, activists and liberal politicians of the moment, including Poitier, King and Robert F. Kennedy, who had begun his historic presidential run. Of the 25 people Belafonte interviewed, 15 were black.

In the 1980s, Belafonte’s attention shifted to Africa. He helped found the organization USA for Africa, which, in 1985, conceived of the hit song “We Are the World” to raise money for famine relief in Ethiopia. He was one of the many celebrity singers who joined in the chorus of the star-studded song written by Michael Jackson and Lionel Ritchie.

At the same time, as a head of Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid, Belafonte played a key role in the successful movement to get American and European celebrities to boycott apartheid South Africa.

“To speak out against an unjust war was treasonous, to speak against the treatment of Blacks made you a Communist dupe,” Belafonte said of his efforts. “But if you feel in your heart that you have a responsibility because of your good fortunes to advance justice and human rights, then you hang in.”

Belafonte expressed his sometimes-radical views freely and consistently throughout his life, regardless of the controversy they elicited.

He opposed the Iraq War as vehemently as he had the Vietnam War decades earlier. In a 2006 interview with Venezuela’s then-President Hugo Chavez, an authoritarian leftist, Belafonte called then-President George W. Bush “the greatest terrorist in the world.”

In recent years, Belafonte has shown a preference for progressive Democratic politicians, such as former New York Mayor Bill De Blasio. After the 2016 presidential election, Belafonte regarded thwarting Trump as his top priority.

“Just as the Republicans and the Tea Party made Barack Obama’s term ungovernable, I think we, citizens of the union, have the capacity and the responsibility to make sure that Trump’s philosophy and his view of life and fellow beings does not endure,” he said in January 2017. “And I will spend what time I have left on this good earth to make sure that I have contributed all that’s at my disposal to make him unworthy.”