Time for a quick breathing exercise. Close your eyes and, while you breathe slowly, focus on your belly and chest. Feel those areas expand and contract, concentrate on the air moving through your nose and windpipe, filling your chest.

I did not do a great job of describing it, but mindful breathing is a technique designed to draw people’s attention, in a non-judgmental way, to thoughts, feelings, and sensations without interference from thoughts about the past or future. When practiced regularly, mindfulness reduces stress, improves mood; in my case, it has helped me get ahead of chronic pain.

But has mindfulness made me selfish?

On one hand, many mindfulness practices have emerged out of Eastern cultures, where there is a relative emphasis on social interdependence and a relative de-emphasis on the selfish individualism of many Western cultures.

On the other hand (and there’s always another hand, in the world of rhetoric), what happens when mindfulness collides with Western independence? Will a fiercely independent person like me become less generous if I practice mindfulness? Will all that focus on self and present drawing me away from other people’s concerns?

Here is how a research team led by Michael Poulin answered the question.

First, Poulin’s team randomized a group of undergraduates to either undergo a mindfulness breathing exercise or to let their minds wander. Then the team had all the students read a story about a local charity. Next, they asked students if they would stay for a little while longer and stuff envelopes for the charity. Finally, they measured how many envelopes the students stuffed before they left the lab.

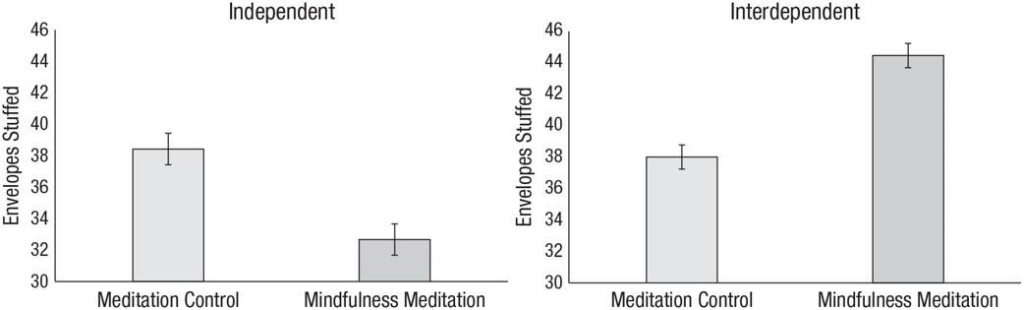

Pretty straightforward research design: randomize people to two groups, and see if mindfulness alters their charitable motivation. By that measure, the answer is no. Students in both groups stuffed an average of about 38 envelopes.

Here’s where things get more interesting. Earlier in the semester, Poulin’s team had measured where people saw themselves on a continuum running from independent to interdependent. How much do their close relationships, for example, define their identity.

Poulin’s team found that mindfulness changes charitable intentions in different ways for people who are either independent or interdependent. I am super independent, for example. If I were a participant in Poulin’s study, the mindfulness exercise might have made me stuff fewer envelopes. By contrast, interdependent people would have probably been influenced to stuff more envelopes after practicing mindfulness. Here’s a picture of that finding:

MIndfulness Reduces Charitable Actions for Independent People

I now have a new goal in my life. I need to simultaneously practice mindfulness while trying to increase my charitable motivation. How mindful any of us are is not fixed in our genes nor is it determined by our culture. Many of us can benefit from practicing mindfulness. At the same time, our level of independence and interdependence is not fixed, either. With practice, all of us can work to be mindful of the present while still caring about our communities.