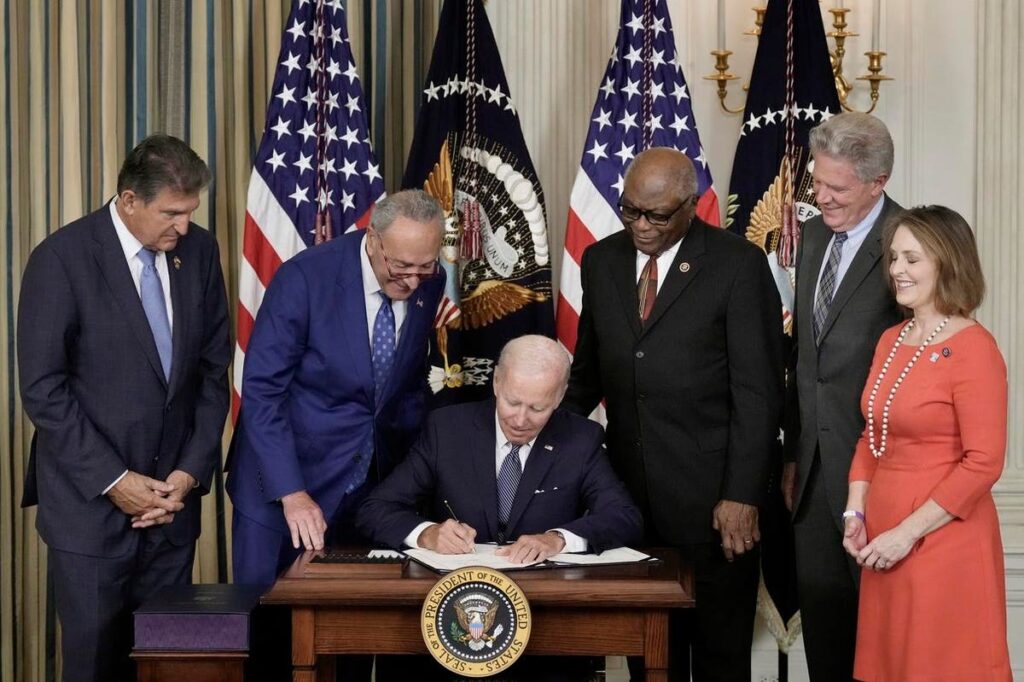

WASHINGTON, DC – AUGUST 16, 2022: President Joe Biden (C) signs the Inflation Reduction Act with … [+]

Last week, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced its selection of the first 10 prescription drugs that will be subject to Medicare price negotiations under the Inflation Reduction Act. Conspicuously, four of the drugs CMS included in the first batch of 10 face generic or biosimilar competition before or during 2026 when the “maximum fair prices” will get implemented. Another pharmaceutical which CMS chose is more than 25 years past its initial date of approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

Going forward the IRA may de facto alter the incentives pharmaceutical companies have to pursue evergreening strategies, as having generic or biosimilar competition can exempt a drug from selection for price negotiation. However, questions remain regarding CMS guidance on what is termed “meaningful” competition.

Though not explicitly stated in the IRA, lawmakers have expressed concern about some of the barriers to competition which originator drug companies have established. These includes strategies such as patent “evergreening. This term refers to the continuing extension of patent rights on a specific product which serves to block generic and biosimilar competition from entering the market.

A recently released study in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that between 2000 and 2015 there was a 200% increase in patents filed by originator companies, often involving relatively minor changes to dosages and formulations. Such patent “thickets” can delay generics and biosimilars from entering the market.

Among the 10 prescription drugs selected by CMS for price negotiation, Stelara (ustekinumab), Xarelto (rivaroxaban), Januvia (sitagliptin) and Entresto (combination of sacubitril and valsartan) have biosimilar or generic competition pending soon, though there is uncertainty regarding the exact timing of market entry. And then there’s Enbrel (etanercept), which is a special case. An Enbrel-referenced biosimilar, Erelzi (etanercept-szzs), was approved in 2016. But its U.S. launch has been delayed by patent litigation until 2029. By the time an Enbrel-reference biosimilar launches in the U.S. the originator product will have had roughly 30 years of exclusivity.

Notably, besides the manufacturer of Enbrel, the makers of Stelara, Xarelto and Entresto have also pursued legal action in connection with holding off the potential launches of biosimilar or generic competitors.

Ambiguity in CMS guidance

At the time a drug is selected for Medicare price negotiation a small or large molecule must be at least seven or 11 years, respectively, removed from its original FDA approval. But after this CMS guidance—which operationalizes the IRA—becomes ambiguous.

Current guidance states that the availability and “bona fide” marketing of a generic or biosimilar will exempt the originator drug from selection for Medicare price negotiation. However, the determination of marketing on a bona fide basis is far from clear. It is not based on a quantitative definition or a numeric threshold. Rather, CMS uses the phrase “totality of circumstances” which entails examination of unspecified utilization and sales data, assessment of whether the generic or biosimilar is “readily available for purchase” and ascertainment of the existence of any agreements between makers of the brand and generic drug which might limit availability of competitors. In turn, CMS will evaluate whether “meaningful” competition exists.

The phrases “bona fide,” “totality of circumstances” and “meaningful” are subject to interpretation.

CMS guidance further compounds the problem of lack of clarity by introducing more ill-defined language when it states that originator manufacturers of biologics may seek a “delay” in selection of their drugs for negotiation if there is a “high likelihood” of biosimilar market entry “within two years of the publication date of the selected drug list.”

To illustrate how problematic the ambiguity is, Stelara was chosen for price negotiation last week despite a high likelihood of biosimilar market entry by January 2025, which is before the two year delay window ends. This raises the question why Stelara was picked. Did the sponsor not apply for a delay? Or, if an application was submitted, is it the case that perhaps CMS wants to first ensure that there will be “meaningful” competition. But this in turn begs the questions, what is meaningful and how much influence Stelara’s sponsor has on biosimilar uptake.

Is it sufficiently meaningful when Janssen (Stelara’s sponsor) simply allows for biosimilar competition? Or does meaningfulness indicate a numeric threshold in terms of numbers of competitors or actual market share figures? CMS guidance is silent on this.

In the cases of Xarelto and Januvia, generics won’t be available until at some point in 2025 and 2026, respectively. This implies that it’s very likely that the two pharmaceuticals’ maximum fair prices will only apply for one year, unless of course the issue of meaningful competition crops up and CMS determines that it isn’t sufficient.

Accompanying these problems is CMS’s apparent presumption that the power to exert influence on generic or biosimilar uptake mostly resides with originator drug manufacturers. CMS appears to ignore the important role that payers and pharmacy benefit managers have as it’s their formulary decisions which affect adoption of generics and biosimilars. Moreover, biosimilar sales depend on considerations such as physician and patient trust regarding interchangeability of originator and biosimilar products. In most instances, it takes multiple parties besides originator drug makers to impact generic and biosimilar uptake.

Branded drug companies fearful of net price erosion from CMS negotiations will be faced with a calculus in which the pros and cons of pursuing litigation will be weighed against being exempt from Medicare price negotiation.

Firms may well decide that seeking legal action to preempt competition isn’t worth it. As such, the threat of Medicare drug price negotiations could indirectly lead to a shorter period to generic and biosimilar competition.

But to facilitate such decisions there would need to be better clarity in CMS guidance around generic and biosimilar competition. This implies the use of unambiguous language to avoid (possibly legal) conflicts around terms like “totality of circumstances,” “bona fide,” “meaningful” and even “high likelihood.” In this context, maybe adopting more straightforward and simpler language is better.

For example, a branded medicine could be exempted from price negotiation once it’s known that a generic or biosimilar is on the market (or in the case of biosimilars will be within two years) and exclusionary rebates or contracting that forecloses such competition isn’t in play.