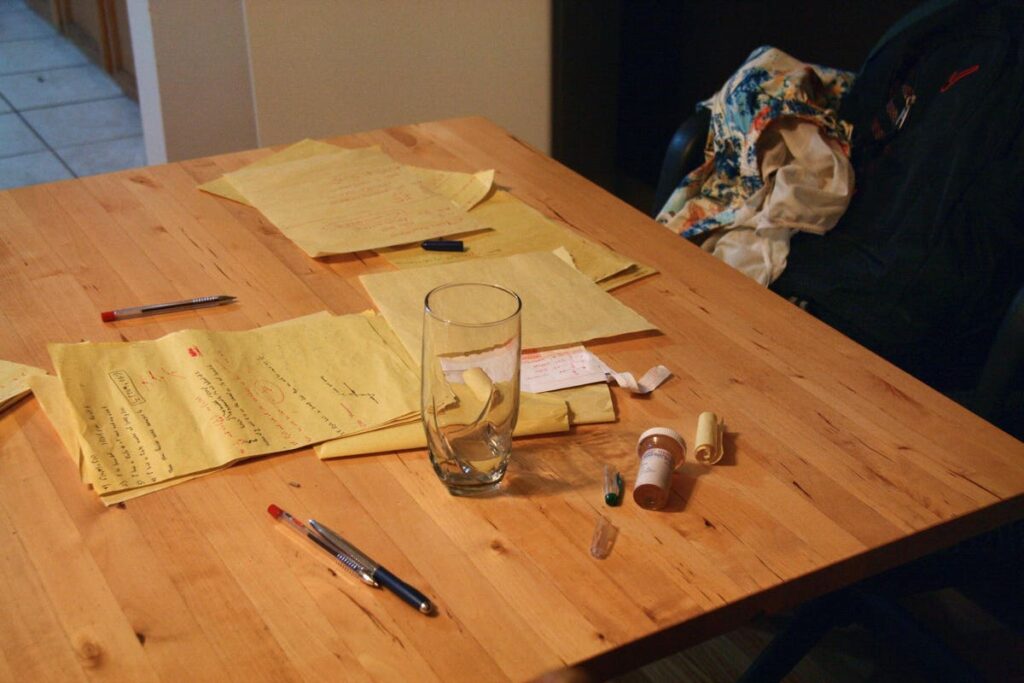

Empty pill bottle for the drug Aderall rests on the table by a university student’s exam study notes … [+]

A new JAMA Psychiatry study found no evidence that links the use of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder stimulant medication during childhood to a higher risk of frequently consuming alcohol, tobacco or marijuana in early adulthood.

To date, multiple studies have found that people with ADHD are far more impulsive than their neurotypical counterparts, which puts them at an increased risk for substance abuse disorder during adulthood. Stimulant medications that are specifically used to treat ADHD can help in reducing impulsivity. But some researchers and clinicians alike have raised concerns that prescribing stimulant medication to children with ADHD might make them more prone to harmful substance use later in life.

“Stimulants are the first-line treatment recommended for most individuals with ADHD — the drug class is an evidence-based treatment with few side effects,” said Brooke Molina, lead author of the study and a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh in a press release. “Because stimulant medications are classified by the Drug Enforcement Administration as schedule two substances with the potential for misuse, many people fear that harmful substance use could result.”

“We hope the results of this study will help educate providers and patients,” Molina added in her statement. “By understanding that stimulant medication initially prescribed in childhood is not linked to harmful levels of substance use, I anticipate that parents’ and patients’ fears will be alleviated.”

To investigate further, Molina and colleagues assessed 579 children with ADHD over a span of 16 years from their childhood to early adulthood. When the study began, the mean age of the children was 8.5 years old. Over 60% of them were white. The other 115 participants were African American (20%) or Hispanic (8%).

Following the 16-year long assessment, the researchers observed that 36.5% of them were smoking tobacco on a daily basis and 29.6% reported using marijuana every week. Around 21% of the participants indulged in heavy drinking at least once a week.

During adolescence, 60% of the participants were using ADHD stimulant medication like methylphenidate (minimum of 10 mg to a maximum of 53 mg a day). By early adulthood, only 7.2% of them were still taking methylphenidate.

“Results showed no evidence that stimulant medication use prior to study entry or its interaction with cumulative years of stimulants increased the likelihood of any substance use at a mean age of 25,” the researchers noted. “Our findings may differ from recent US commercial health care claims data because we examined more prevalent substance use behavior vs rare presentations to the emergency department.”

“Another long-standing hypothesis is that early, continuous stimulant treatment should protect children with ADHD from harmful substance use. Our analyses did not show that longer duration of stimulant treatment predicts less substance use in adulthood,” they added. “Even if stimulants were initiated before the mean age of 8 years, our results were not consistent with the hypotheses of protection or harm in relation to substance use or substance use disorders.”

The researchers further highlighted that while methylphenidate improves cognitive performance, those benefits disappear once someone with ADHD discontinues taking the medicine. “There still remain possible benefits to combined pharmacotherapy (including stimulants), psycho-education, and psychotherapy for individuals with current ADHD and substance use disorder,” they concluded.