NEW YORK — A nurse supervisor at Montefiore Comprehensive Health Care Center in the Bronx was delivering her start-of-shift updates and mantras — “Covid is not finished with us … clean, clean, clean!”— to the clinicians and administrative staff bunched up nearby. Hawa Abraham, not one or the other, stood among them.

It was going to be another busy day at the clinic, with 150 patients expected, and Abraham, a community health worker, would be seeing several herself. One was among her first patients when she started at Montefiore almost a year ago: a Guinean woman whose heart was set on getting a job as a bus attendant so her work hours would align with her children’s schedules.

Abraham’s presence in the huddle represents the leading edge of a movement to bolster the role of community health workers — frontline public health workers who use their life experience and deep knowledge of communities to bridge gaps between patients and medical and social services. Abraham tends to those gaps from her office, the room closest to the sliding-door entrance off 161st Street between Morris and Park avenues, in a district with a poverty rate twice that of the citywide average.

“There’s a lot of potential for CHWs,” said Jessica Haughton, the associate director of the Community Health Systems Lab at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore’s research arm. With so much money and waste wrapped up in health care, she said, “there is a little bit of change starting to happen, like more awareness about prevention and the importance of primary care, and how CHWs can have a role in that, both for social determinants of health but also just for health, education, and prevention.”

In most of the U.S., CHWs don’t work as full colleagues alongside clinical staff, but rather are contracted through nonprofit organizations. This was true even during the pandemic, when public health officials started to see how important they were to getting older adults vaccinated for Covid-19. Funded by federal grants, swaths of CHWs were hired for vaccination campaigns in hesitant and underserved communities in homes, the streets, and community hubs like churches — less so in hospitals or clinics.

By contrast, the Community Health Worker Institute at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, begun in 2021, incorporates CHWs directly into the Montefiore health system and is building a pipeline to sustain and advance these workers. Its goals mesh with a larger movement to solidify the CHW as a critical public health professional, whether employed by a hospital system or not. In 2018, the World Health Organization issued guidelines recommending that CHWs be integrated and supported within health systems. In the U.S., local CHW and promotora organizations came together in 2019 to form the National Association of Community Health Workers.

The association is campaigning for federal recognition and broader Medicaid reimbursement of CHW services. But the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CHW data does little to help, said Denise Octavia Smith, executive director of the NACHW. First, “CHW” is not always reflected in a person’s title, so it’s tough to know if an outreach worker, navigator, care coordinator, liaison, or worker in another role identifies as a community health worker. Health care payers or funders are also inconsistent about their use of “CHW.” So when they ask employers to hire outreach workers or other roles, “we don’t know who is really a trusted, frontline public health worker, who shares relationship, culture, and life experiences with the population being served,” Smith told STAT via email.

Since employers are similarly inconsistent in using the Department of Labor classification, the accuracy of CHW counts in the workforce is dubious. Moreover, nearly 30% of the CHWs Smith and her team surveyed nationwide said they don’t earn an equitable wage and 41% said they don’t get compensated for working overtime — calling into question the accuracy of figures like salary.

Regardless of their exact numbers, thousands are losing their jobs now that pandemic funding for CHWs has all but dissipated with the end of the Covid health emergency, Politico has reported. Experts say the most recent cycle of rapid attention and receding support for CHWs isn’t just tied to the pandemic. The murder of George Floyd in 2020 brought a sudden interest in addressing social injustices alongside health disparities.

“Community health workers became this momentary darling child,” said Daniel Palazuelos, the director of community health systems for the nonprofit Partners in Health. “It was wonderful that our CHW colleagues finally got the recognition that they deserve because they are so powerfully positioned to add unprecedented functionality to our health system. That this same system can so easily walk away from both the CHWs and the people they serve says a lot about the system, and its faltering commitment to equity.”

Despite the headwinds, community health workers say they are gaining ground in Washington and laying roots in programs like Montefiore’s.

A nationwide push for inclusion

For Smith, the longtime omission of CHWs in federal policy almost feels personal. Smith comes from a family of leaders in community health care. Her grandmother was a Stephen Minister, a layperson trained to give one-on-one care. She would have Smith gather eggs and other food for people in need. Smith’s mother was an HIV advocate who worked for the Connecticut Department of Health for years and brought Smith to rallies and protests.

In the 1990s, Smith was in San Francisco collaborating on an HIV theater education project with a friend who, like her, had lost a family member to AIDS. In developing the play, Smith partnered with people who were living with HIV as well as social workers, primary care doctors, and outreach workers.

“I knew at that moment that all of the art and all of the engagement that I could do couldn’t beat people who were making direct connections between the resources and services that people needed to live a long and healthy life,” Smith told STAT.

With the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 came a push to make health systems more accountable to outcomes, and policymakers “started to look more upstream,” said Palazuelos, who is also an assistant professor of global health at Harvard Medical School. Early health intervention gets the best return on investment, and CHWs are one of the key mechanisms for it, he told STAT.

Connecticut took part in the Obamacare Medicaid expansion, and Smith was called upon to develop training and certification for hundreds of CHWs and related professions.

“People don’t think that we are leaders because we don’t have academic credentials, or we’re not doctors,” Smith said. “The reality is not the case at all.”

The commitment of CHW leaders and allies led to the founding in 2019 of the National Association of Community Health Workers. It was a space to unify diverse voices across factors like race, ethnicity, gender, geography, and title. Much of the foundation had been built behind the scenes: CHW and promotora organizations had existed all over the country for years, some of them for decades, partnering at the local level and advocating for policy changes.

When COVID came, the time was ripe for collaboration at the national level. The newly established organization released its national policy platform in March 2021, calling for federal recognition through accurate tracking, greater inclusion of CHWs in workforce decision-making processes, and setting up permanent streams of funding for CHWs. It demands protections like a living wage and equitable benefits and building a sustainable pipeline. The platform also urges partnerships to ensure direct reimbursement and investments in community-based organizations that employ CHWs.

Support for the national platform is bipartisan, Smith said. When the NACHW visited the Hill in March, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle — from Democrats to conservatives like South Carolina senators Lindsey Graham and Tim Scott — met with CHW leaders, even if they didn’t fully endorse the platform. And back in 2019, Republican governor Greg Abbott declared a community health worker day for Texas. The NACHW is continuing to advocate in and out of Washington, launching its national awareness week in August.

The all-in Montefiore model

Closing out the huddle at the Montefiore ward, the nurse supervisor pulled out a Norman Cousins quote.

“‘The human body experiences a powerful gravitational pull in the direction of hope,’” she said. “‘That is why the patient’s hopes are the physician’s secret weapon. They are the hidden ingredients in any prescription.’”

At Montefiore, the prescription for patients who indicate certain social needs is a warm hand-off to a CHW — emphasis on the “warm.” Abraham makes sure to praise patients for every small step they take to secure a resource.

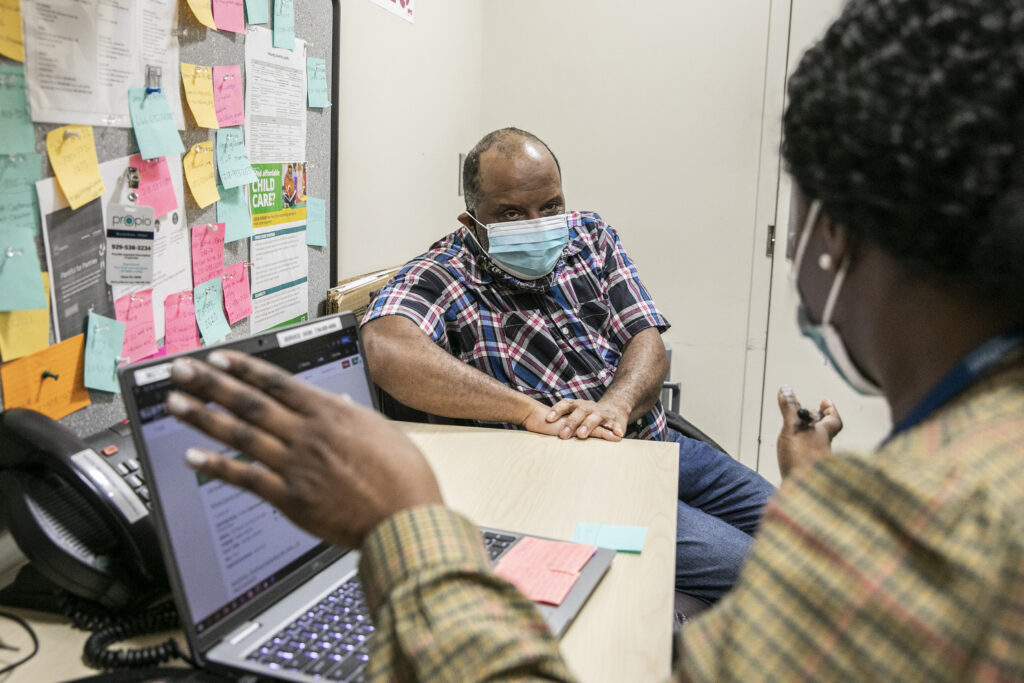

After the staff huddle, Abraham zipped back towards her office. She had a follow-up call with a 38-year-old patient, Calvin Saunders, who had suffered a stroke and heart attack last April and May. When they had first met, Saunders was in bad shape, speaking only with great difficulty and lacking a place to sleep or access to food. Social-needs triage was in order.

“I said, ‘you know what, let’s get you some food, because you need that to survive,’” Abraham recalled. “And he begged me that he didn’t want to go into the shelter system, so if there’s any way I could help him to get his own place.”

Abraham had made no promises other than that she’d do everything she could. Meanwhile, she applied for SNAP benefits on his behalf with AccessHRA, an online tool to upload supporting documents. She sent him to soup kitchens and food pantries while waiting for full approval. She sent an application to Montefiore’s Housing at Risk Program.

During the follow-up call, she asked if he’d gotten support from HARP yet. He was still without shelter but had heard from a HARP representative, he said. That’s a good sign, she assured him — it meant he’d been approved for housing assistance and the process was moving forward.

Saunders’s speech was still stilted, sentences punctuated by pauses and labored breathing, effects from the stroke. He knew it better than anyone, telling Abraham, when asked about his health, that his “condition got worse, heart very very weak, speech not well … going to therapist … after surgery.”

Abraham, safeguarding his energy, drew the call to a close with a review of the resources she’d be emailing him, the text he should watch for, and the call she’d be making within a week. Before they hung up, Saunders served up a thank you: “You’ve … been helping me so much. … No one helped me before accident. So I appreciate you very much.”

The model Abraham is working in is a forward-thinking one, social medicine experts told STAT. Part of what makes it relatively unique is how embedded community health workers are with clinical professionals in the clinics and in data systems, and how Montefiore is tracking their care for research with Albert Einstein College of Medicine. What’s more, collaborative partnerships with a community college and one of the largest healthcare unions in the nation, 1199, help create a sustainable pipeline of CHWs.

It’s new, too, within the Montefiore health system. Despite housing a social medicine program that dates back to 1978, Montefiore has long partnered with community-based organizations to employ CHWs to work outside their clinics. It wasn’t until July 2021 that Kevin Fiori, Montefiore’s director of social determinants of health at the Office of Community & Population Health, and his team established the Community Health Worker Institute. And it wasn’t until August 2022 that CHWs employed under this model first started seeing patients in their primary care and OB-GYN clinics.

This was two decades after Fiori had first been exposed to the power of CHWs’ expertise during his time in Togo as a Peace Corps health specialist volunteer. Working among CHWs, like a woman named Rose, who were living with HIV and sitting on a bench chatting up others with HIV about antiretroviral therapy, he said, was a “career-changing moment.”

Fiori saw that “even if you had the best-trained clinical personnel there, them saying those words would mean something very different than when Rose said those words because she actually had a shared lived experience with the patient,” he said. “And that’s something you can’t train. You can give her tools. But having that kind of expertise on what it really means to walk in that person’s shoes, and to empathize on that level — I think that is a lot of what’s missing sometimes in our clinical care.”

The idea behind the Institute was to embed and integrate CHWs within health service operations, rather than employ them in some side program, and to use internal data to drive the program’s design and direction. The Community Health Systems Lab at Albert Einstein has primarily worked with CHWs in Togo to look at programs’ effectiveness on the ground. Now the CHS Lab has fresh research ground to cover in the Bronx.

The Community Health Worker Institute was also built as a professional pipeline for CHWs. At its most basic, it’s a place to get free training and college credit towards an associate degree and certificate as a CHW at Hostos Community College in the Bronx. It’s a pathway to get accredited as a CHW through an apprenticeship recognized by the New York State Department of Labor. It’s also a way to become, if desired, something else.

Abraham’s initial dream, after coming to the U.S. from Sierra Leone, was to continue on the nursing track she had started in Guinea when her family fled home. Then Covid came, and Abraham couldn’t unsee the disparities wrought by information gaps.

“I want to be that person on the front line to help the less privileged navigate the system,” she said.

Sharing lived experiences

Abraham knows all too well what it’s like to navigate confusing systems for accessing food and housing in the Bronx. With patients in similar situations, she often relays her own anecdotes of figuring things out after migrating to the U.S. more than 12 years ago.

Speaking French is an additional way in which Abraham, like Fiori, connects with some Senegalese and Malian patients, who reflect a solid demographic at Montefiore. In Abraham’s case, French wasn’t her native tongue in Sierra Leone — English was — but she learned as a refugee in Guinea, she told a patient in her office. The patient, an Ethiopian woman named Mabuba Abafita, had been taking ESL classes and smiled when complimented over her English, kohl-lined eyes crinkling.

But she was antsy. Abafita needed a stable job so she could bring her kids to the U.S. She had been working on a time-limited work authorization. She was open to training as a cashier or as a home health aide, so Abraham pulled up two training sites near her and asked Abafita to check her phone for an alert.

Abafita was more hesitant about the immigration legal assistance Abraham offered. It’s free and won’t affect your process, Abraham reassured her. She broke down steps in the application system, sensing this information was her best shot at debunking Abafita’s belief that contacting the immigration help center meant her application would start again at zero. But the hesitation held. Abraham left it at “It’s up to you.” Even among confidantes, for patients with a certain immigration status or who are otherwise marginalized, shared lived experiences might not be enough.

Some of these interactions in medical settings are often initiated by social workers. But when the role of a CHW is to help connect patients to social services and navigate housing and other applications, it frees up social workers to focus on clinical therapy, said Renee Whiskey-LaLanne, associate director of the Community Health Worker Institute. Case managers or care coordinators typically focus on a smaller group of patients for a longer period of time, while a CHW is focused on the community at large, she explained. Whiskey-LaLanne herself is a former CHW whose days were once spent in barber shops and the homes of pregnant women, embedded in communities in Philly and New York to educate on topics from hypertension to the toxicity of Raid sprays.

When clinicians instead treat CHWs like glorified administrative assistants, their expertise as trusted messengers and system navigators gets wasted. Hyper-professionalization embedded in the U.S. medical education plays a role, experts said.

“It bothers me when I hear health care providers saying, ‘Oh, yeah, we could use CHWs to remind [patients] of their appointments, and we could use them to go and do health education,’” said Sonya Shin, an associate professor of medicine and Department of Global Health and Social Medicine affiliate at Harvard Medical School. “They think of them as these sort of workforce multipliers, without realizing that actually they’re on par with what I can do as a doctor, but just a totally different skill set.”

Shin and other experts pointed to studies showing improved health outcomes or health utilization cost-saving for systems where CHWs interact with patients. In Peru, where Shin has worked, CHWs have been around for a long time, ensuring that people with tuberculosis are taking their pills. Studies suggest that it helps — researchers found a link between home visits by these workers who have community and family context and patients’ access to medication and compliance.

“The irony is that there’s tons of data around the evidence base … and yet there’s something in the United States that’s missing, in terms of a tipping point,” said Shin.

What’s missing, she said, is a shift in the culture — and operations — of health systems in the U.S. A 2017 study, of which Shin was an author, looked at a program that better integrated Navajo Nation CHWs into the local health care system. The community workers were given training, access to patients’ electronic health records, and culturally appropriate health promotion materials for home visits. Researchers found that CHWs felt more validated by both clinicians and the people they served; and patients with diabetes had better lipid and diabetes control and saw their providers more regularly.

Montefiore is a health system where social medicine models were adopted early on, Fiori said. Still, not all of his colleagues grasped the value of the CHW Institute from the start. But bit by bit, he said, they became some of the institute’s biggest believers. They had glimpsed how patients responded to CHWs and how the latter responded to these patients’ problems.

Fiori often meets Montefiore patients with complex housing issues, like a mother with five children, two of whom were newborn twins. She had had mold and water in the bathroom and bedroom for months, and her apartment building super wasn’t lifting a finger.

“The idea of having these new twins come home to this was just terrifying to her,” said Fiori. “So we had got her hooked up with one of the CHWs, and — you know, we haven’t totally resolved the problem. But we’ve gotten a lot closer… She just mentioned how much it matters … feeling cared for.”

Closed cases and new chapters

For other patients, the case does get closed. The woman who first came to Abraham for help securing a bus attendant job, Fatoumata Camara, had racked her brain trying to figure out how to apply. She longed to spend more time with her boys, and the health insurance that would come with the position was a major plus.

On her off-hours, Abraham said, she’d stand in the street and check for buses. She’d ask bus attendants how they had gotten the job. At last, a computer search turned up the right number for Camara to call. The week before starting her new job, Camara stopped by the clinic to see Abraham, give her thanks and pass on something a tad more concrete.

“She brought me a copy of the application,” recalled Abraham, breaking out in a grin. “She said, ‘I’m gonna give it to you if you use it to help other people.’” She accepted the condition.

She also recently accepted an offer to follow this fervor to help her community through a different path. In a research internship with the CHS Lab last semester, she wrote a literature review and learned how colleagues co-designed surveys, to “know what people are about … ‘cause you can’t just assume.” Abraham now plans to study epidemiology at Columbia University in the fall – aided by a Hostos Community College scholarship she won – and pursue a masters in public health. Her ultimate hope is to return to Sierra Leone and help people back home meet their social and health needs.

It’s a testament to a goal of the CHW Institute and the national CHW movement: to empower community health workers to go farther than they imagined for themselves — or than the U.S. medical system designed for them. With the proper support, advocates suggest, community health workers can choose whether their work lies in leading large-scale movements like Smith or Whiskey-LaLanne do, or in working directly with communities alongside clinicians, brokering trust in a system where that currency is hard-earned. Experts in the in-betweens, they might choose to be cheerleaders navigating systems, educators at churches or barber shops, or service sleuths whose patients approach with an offer they won’t refuse.

“Sometimes I’m even excited more than the patient,” Abraham said. “I just want to do anything that can help the public, my community, people like me.”