The Drug Enforcement Administration is holding off on making sweeping changes to the way certain drugs can be prescribed via telemedicine — for now.

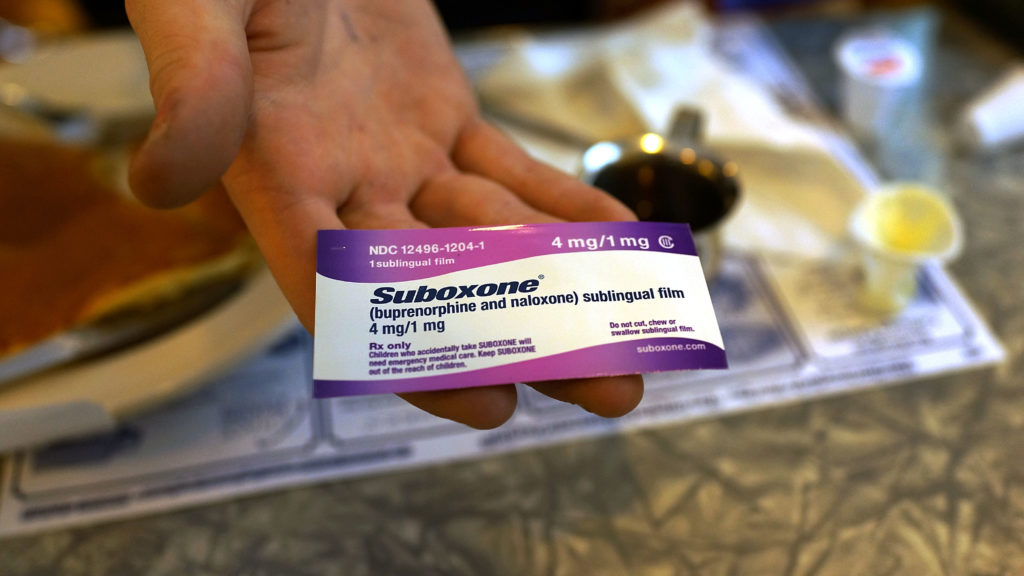

The DEA announced Wednesday that it was temporarily extending its Covid-era emergency telehealth policies, allowing doctors continued leniency in how they prescribe some controlled substances. The affected medications include buprenorphine, the most common medication used to treat opioid addiction, and stimulants like Adderall used to treat ADHD.

“We recognize the importance of telemedicine in providing Americans with access to needed medications, and we have decided to extend the current flexibilities while we work to find a way forward to give Americans that access with appropriate safeguards,” Anne Milgram, the DEA administrator, said in a statement.

The DEA has not yet announced a decision about its future policies. A draft proposal released in February, however, generated widespread criticism in addiction medicine circles. The pushback included 38,000 public comments to the DEA’s proposal, which the agency said was a record.

In particular, doctors, advocates, and even Democratic members of Congress warned that reimposing restrictions on buprenorphine could cause a spike in opioid overdose deaths, which are already at record levels.

Milgram said in a statement then that the rules were aimed “at ensuring the safety of patients.” Opponents, however, warned that it would create an instant access crisis for thousands of patients who were able to access buprenorphine during Covid-19 thanks to the new telehealth rules.

Buprenorphine is one of just three medications approved to treat opioid use disorder, and the only drug that treats withdrawal symptoms and can be prescribed directly by a physician to a patient. While buprenorphine is a controlled substance, it is far less potent or risky than opioids used to treat pain, and carries a vastly lower risk of overdose.

Under the emergency pandemic-era policies, doctors could write buprenorphine prescriptions to patients who they had only evaluated by phone or by video. Previously, patients needed an in-person examination before receiving buprenorphine.

The DEA’s new policies for buprenorphine would still allow doctors to prescribe buprenorphine after a telemedicine visit. To continue taking the medication, however, they would need to visit their prescriber for an in-person exam within 30 days.

Patients who began buprenorphine treatment under the emergency rules would have a more lenient 180-day grace period before they, too, must visit their provider in-person or risk being cut off from the medication.

Addiction medicine groups, including the American Society of Addiction Medicine, have pushed back strongly against the in-person requirement for buprenorphine, arguing it had no real safety benefit and that it would pose an arbitrary obstacle to treatment.

“I don’t want federal rules dictating to me when I have to cut somebody off a medication that, on the basis of the information available to me, is still appropriate for the patient,” Brian Hurley, ASAM’s president, told STAT then.

The DEA’s proposal and the controversy surrounding it are emblematic of a long-running tension between the public health field and law enforcement. While the public health world favors a treatment-centric approach, law enforcement officials typically favor strict crackdowns not only on illicit opioids and black-market prescription painkillers, but also, in some cases, on drugs used almost exclusively to treat addiction.

Biden’s health secretary, Xavier Becerra, signaled support for the proposal at a STAT event in March. But he noted then that it had not been finalized, and acknowledged that the DEA has a “different mandate” than public health agencies, appearing to acknowledge that the proposal was rooted more by law enforcement philosophy than public health strategy.

STAT’s coverage of chronic health issues is supported by a grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies. Our financial supporters are not involved in any decisions about our journalism.